-

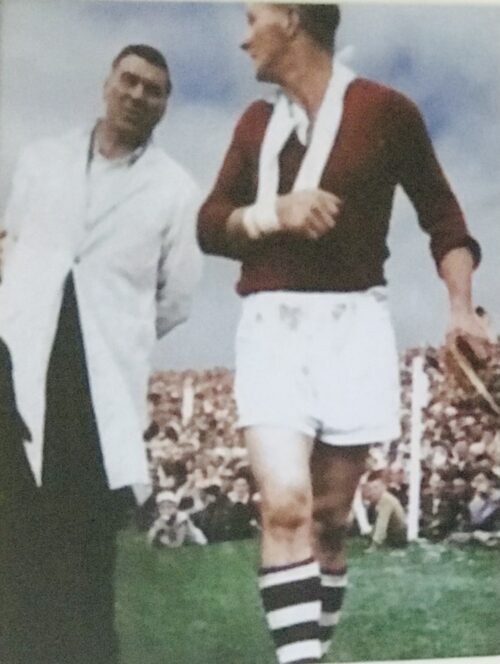

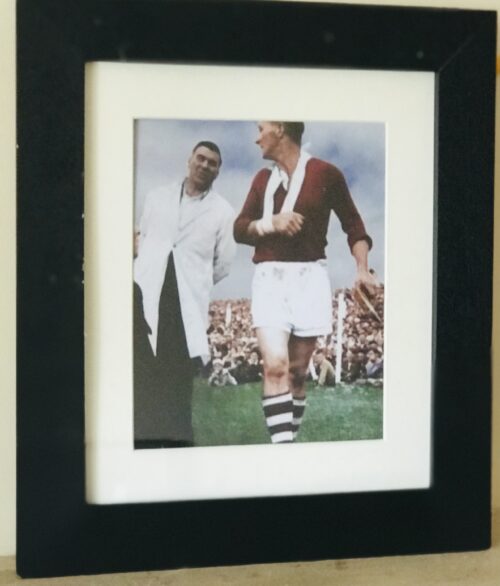

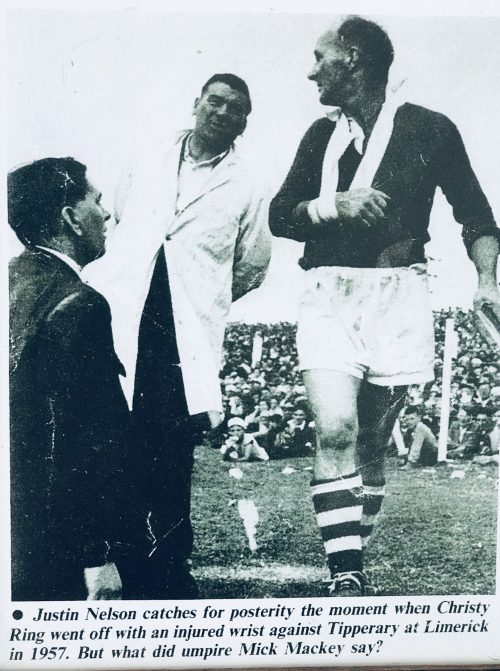

38cm x 33cm This time a colour version of the iconic photograph taken by Justin Nelson.The following explanation of the actual verbal exchange between the two legends comes from Michael Moynihan of the Examiner newspaper. "When Christy Ring left the field of play injured in the 1957 Munster championship game between Cork and Waterford at Limerick, he strolled behind the goal, where he passed Mick Mackey, who was acting as umpire for the game. The two exchanged a few words as Ring made his way to the dressing-room.It was an encounter that would have been long forgotten if not for the photograph snapped at precisely the moment the two men met. The picture freezes the moment forever: Mackey, though long retired, still vigorous, still dark haired, somehow incongruous in his umpire’s white coat, clearly hopping a ball; Ring at his fighting weight, his right wrist strapped, caught in the typical pose of a man fielding a remark coming over his shoulder and returning it with interest. Two hurling eras intersect in the two men’s encounter: Limerick’s glory of the 30s, and Ring’s dominance of two subsequent decades.But nobody recorded what was said, and the mystery has echoed down the decades.But Dan Barrett has the answer.He forged a friendship with Ring from the usual raw materials. They had girls the same age, they both worked for oil companies, they didn’t live that far away from each other. And they had hurling in common.We often chatted away at home about hurling,” says Barrett. “In general he wouldn’t criticise players, although he did say about one player for Cork, ‘if you put a whistle on the ball he might hear it’.” Barrett saw Ring’s awareness of his whereabouts at first hand; even in the heat of a game he was conscious of every factor in his surroundings. “We went up to see him one time in Thurles,” says Barrett. “Don’t forget, people would come from all over the country to see a game just for Ring, and the place was packed to the rafters – all along the sideline people were spilling in on the field. “He came out to take a sideline cut at one stage and we were all roaring at him – ‘Go on Ring’, the usual – and he looked up into the crowd, the blue eyes, and he looked right at me. “The following day in work he called in and we were having a chat, and I said ‘if you caught that sideline yesterday, you’d have driven it up to the Devil’s Bit.’ “There was another chap there who said about me, ‘With all his talk he probably wasn’t there at all’. ‘He was there alright,’ said Ring. ‘He was over in the corner of the stand’. He picked me out in the crowd.” “He told me there was no way he’d come on the team as a sub. I remember then when Cork beat Tipperary in the Munster championship for the first time in a long time, there was a helicopter landed near the ground, the Cork crowd were saying ‘here’s Ring’ to rise the Tipp crowd. “I saw his last goal, for the Glen against Blackrock. He collided with a Blackrock man and he took his shot, it wasn’t a hard one, but the keeper put his hurley down and it hopped over his stick.” There were tough days against Tipperary – Ring took off his shirt one Monday to show his friends the bruising across his back from one Tipp defender who had a special knack of letting the Corkman out ahead in order to punish him with his stick. But Ring added that when a disagreement at a Railway Cup game with Leinster became physical, all of Tipperary piled in to back him up. One evening the talk turned to the photograph. Barrett packed the audience – “I had my wife there as a witness,” – and asked Ring the burning question: what had Mackey said to him? “’You didn’t get half enough of it’, said Mackey. ‘I’d expect nothing different from you,’ said Ring. “That was what was said.” You might argue – with some credibility – that learning what was said by the two men removes some of the force of the photograph; that if you remained in ignorance you’d be free to project your own hypothetical dialogue on the freeze-frame meeting of the two men. But nothing trumps actuality. The exchange carries a double authenticity: the pungency of slagging from one corner and the weariness of riposte from the other. Dan Barrett just wanted to set the record straight. “I’d heard people say ‘it will never be known’ and so on,” he says.“I thought it was no harm to let people know.” No harm at all" Origins ; Co Limerick Dimensions : 31cm x 25cm 1kgBorn in Castleconnell, County Limerick,Mick Mackey first arrived on the inter-county scene at the age of seventeen when he first linked up with the Limerick minor team, before later lining out with the junior side. He made his senior debut in the 1930–31 National League. Mackey went on to play a key part for Limerick during a golden age for the team, and won three All-Ireland medals, five Munster medals and five National Hurling League medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on two occasions, Mackey also captained the team to two All-Ireland victories. His brother, John Mackey, also shared in these victories while his father, "Tyler" Mackey was a one-time All-Ireland runner-up with Limerick. Mackey represented the Munster inter-provincial team for twelve years, winning eight Railway Cup medals during that period. At club level he won fifteen championship medals with Ahane. Throughout his inter-county career, Mackey made 42 championship appearances for Limerick. His retirement came following the conclusion of the 1947 championship. In retirement from playing, Mackey became involved in team management and coaching. As trainer of the Limerick senior team in 1955, he guided them to Munster victory. He also served as a selector on various occasions with both Limerick and Munster. Mackey also served as a referee. Mackey is widely regarded as one of the greatest hurlers in the history of the game. He was the inaugural recipient of the All-Time All-Star Award. He has been repeatedly voted onto teams made up of the sport's greats, including at centre-forward on the Hurling Team of the Centuryin 1984 and the Hurling Team of the Millennium in 2000. Origins : Co Limerick Dimensions : 28cm x 37cm 1kg

38cm x 33cm This time a colour version of the iconic photograph taken by Justin Nelson.The following explanation of the actual verbal exchange between the two legends comes from Michael Moynihan of the Examiner newspaper. "When Christy Ring left the field of play injured in the 1957 Munster championship game between Cork and Waterford at Limerick, he strolled behind the goal, where he passed Mick Mackey, who was acting as umpire for the game. The two exchanged a few words as Ring made his way to the dressing-room.It was an encounter that would have been long forgotten if not for the photograph snapped at precisely the moment the two men met. The picture freezes the moment forever: Mackey, though long retired, still vigorous, still dark haired, somehow incongruous in his umpire’s white coat, clearly hopping a ball; Ring at his fighting weight, his right wrist strapped, caught in the typical pose of a man fielding a remark coming over his shoulder and returning it with interest. Two hurling eras intersect in the two men’s encounter: Limerick’s glory of the 30s, and Ring’s dominance of two subsequent decades.But nobody recorded what was said, and the mystery has echoed down the decades.But Dan Barrett has the answer.He forged a friendship with Ring from the usual raw materials. They had girls the same age, they both worked for oil companies, they didn’t live that far away from each other. And they had hurling in common.We often chatted away at home about hurling,” says Barrett. “In general he wouldn’t criticise players, although he did say about one player for Cork, ‘if you put a whistle on the ball he might hear it’.” Barrett saw Ring’s awareness of his whereabouts at first hand; even in the heat of a game he was conscious of every factor in his surroundings. “We went up to see him one time in Thurles,” says Barrett. “Don’t forget, people would come from all over the country to see a game just for Ring, and the place was packed to the rafters – all along the sideline people were spilling in on the field. “He came out to take a sideline cut at one stage and we were all roaring at him – ‘Go on Ring’, the usual – and he looked up into the crowd, the blue eyes, and he looked right at me. “The following day in work he called in and we were having a chat, and I said ‘if you caught that sideline yesterday, you’d have driven it up to the Devil’s Bit.’ “There was another chap there who said about me, ‘With all his talk he probably wasn’t there at all’. ‘He was there alright,’ said Ring. ‘He was over in the corner of the stand’. He picked me out in the crowd.” “He told me there was no way he’d come on the team as a sub. I remember then when Cork beat Tipperary in the Munster championship for the first time in a long time, there was a helicopter landed near the ground, the Cork crowd were saying ‘here’s Ring’ to rise the Tipp crowd. “I saw his last goal, for the Glen against Blackrock. He collided with a Blackrock man and he took his shot, it wasn’t a hard one, but the keeper put his hurley down and it hopped over his stick.” There were tough days against Tipperary – Ring took off his shirt one Monday to show his friends the bruising across his back from one Tipp defender who had a special knack of letting the Corkman out ahead in order to punish him with his stick. But Ring added that when a disagreement at a Railway Cup game with Leinster became physical, all of Tipperary piled in to back him up. One evening the talk turned to the photograph. Barrett packed the audience – “I had my wife there as a witness,” – and asked Ring the burning question: what had Mackey said to him? “’You didn’t get half enough of it’, said Mackey. ‘I’d expect nothing different from you,’ said Ring. “That was what was said.” You might argue – with some credibility – that learning what was said by the two men removes some of the force of the photograph; that if you remained in ignorance you’d be free to project your own hypothetical dialogue on the freeze-frame meeting of the two men. But nothing trumps actuality. The exchange carries a double authenticity: the pungency of slagging from one corner and the weariness of riposte from the other. Dan Barrett just wanted to set the record straight. “I’d heard people say ‘it will never be known’ and so on,” he says.“I thought it was no harm to let people know.” No harm at all" Origins ; Co Limerick Dimensions : 31cm x 25cm 1kgBorn in Castleconnell, County Limerick,Mick Mackey first arrived on the inter-county scene at the age of seventeen when he first linked up with the Limerick minor team, before later lining out with the junior side. He made his senior debut in the 1930–31 National League. Mackey went on to play a key part for Limerick during a golden age for the team, and won three All-Ireland medals, five Munster medals and five National Hurling League medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on two occasions, Mackey also captained the team to two All-Ireland victories. His brother, John Mackey, also shared in these victories while his father, "Tyler" Mackey was a one-time All-Ireland runner-up with Limerick. Mackey represented the Munster inter-provincial team for twelve years, winning eight Railway Cup medals during that period. At club level he won fifteen championship medals with Ahane. Throughout his inter-county career, Mackey made 42 championship appearances for Limerick. His retirement came following the conclusion of the 1947 championship. In retirement from playing, Mackey became involved in team management and coaching. As trainer of the Limerick senior team in 1955, he guided them to Munster victory. He also served as a selector on various occasions with both Limerick and Munster. Mackey also served as a referee. Mackey is widely regarded as one of the greatest hurlers in the history of the game. He was the inaugural recipient of the All-Time All-Star Award. He has been repeatedly voted onto teams made up of the sport's greats, including at centre-forward on the Hurling Team of the Centuryin 1984 and the Hurling Team of the Millennium in 2000. Origins : Co Limerick Dimensions : 28cm x 37cm 1kg -

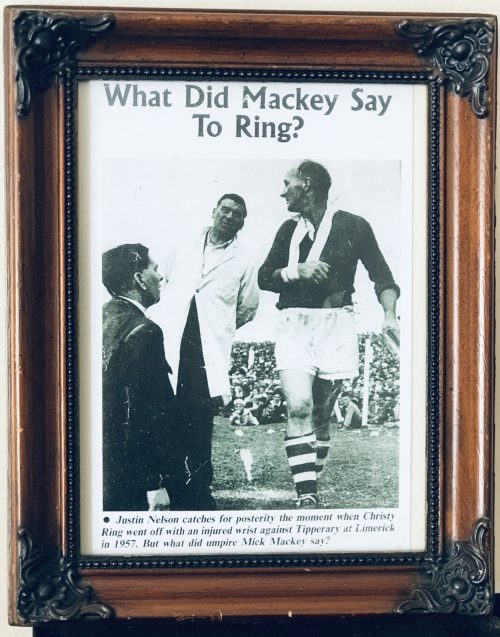

25cm x 20cm Abbeyfeale Co Limerick Nice souvenir of the iconic photograph taken by Justin Nelson.The following explanation of the actual verbal exchange between the two legends comes from Michael Moynihan of the Examiner newspaper. "When Christy Ring left the field of play injured in the 1957 Munster championship game between Cork and Waterford at Limerick, he strolled behind the goal, where he passed Mick Mackey, who was acting as umpire for the game. The two exchanged a few words as Ring made his way to the dressing-room.It was an encounter that would have been long forgotten if not for the photograph snapped at precisely the moment the two men met. The picture freezes the moment forever: Mackey, though long retired, still vigorous, still dark haired, somehow incongruous in his umpire’s white coat, clearly hopping a ball; Ring at his fighting weight, his right wrist strapped, caught in the typical pose of a man fielding a remark coming over his shoulder and returning it with interest. Two hurling eras intersect in the two men’s encounter: Limerick’s glory of the 30s, and Ring’s dominance of two subsequent decades.But nobody recorded what was said, and the mystery has echoed down the decades.But Dan Barrett has the answer.He forged a friendship with Ring from the usual raw materials. They had girls the same age, they both worked for oil companies, they didn’t live that far away from each other. And they had hurling in common.We often chatted away at home about hurling,” says Barrett. “In general he wouldn’t criticise players, although he did say about one player for Cork, ‘if you put a whistle on the ball he might hear it’.” Barrett saw Ring’s awareness of his whereabouts at first hand; even in the heat of a game he was conscious of every factor in his surroundings. “We went up to see him one time in Thurles,” says Barrett. “Don’t forget, people would come from all over the country to see a game just for Ring, and the place was packed to the rafters – all along the sideline people were spilling in on the field. “He came out to take a sideline cut at one stage and we were all roaring at him – ‘Go on Ring’, the usual – and he looked up into the crowd, the blue eyes, and he looked right at me. “The following day in work he called in and we were having a chat, and I said ‘if you caught that sideline yesterday, you’d have driven it up to the Devil’s Bit.’ “There was another chap there who said about me, ‘With all his talk he probably wasn’t there at all’. ‘He was there alright,’ said Ring. ‘He was over in the corner of the stand’. He picked me out in the crowd.” “He told me there was no way he’d come on the team as a sub. I remember then when Cork beat Tipperary in the Munster championship for the first time in a long time, there was a helicopter landed near the ground, the Cork crowd were saying ‘here’s Ring’ to rise the Tipp crowd. “I saw his last goal, for the Glen against Blackrock. He collided with a Blackrock man and he took his shot, it wasn’t a hard one, but the keeper put his hurley down and it hopped over his stick.” There were tough days against Tipperary – Ring took off his shirt one Monday to show his friends the bruising across his back from one Tipp defender who had a special knack of letting the Corkman out ahead in order to punish him with his stick. But Ring added that when a disagreement at a Railway Cup game with Leinster became physical, all of Tipperary piled in to back him up. One evening the talk turned to the photograph. Barrett packed the audience – “I had my wife there as a witness,” – and asked Ring the burning question: what had Mackey said to him? “’You didn’t get half enough of it’, said Mackey. ‘I’d expect nothing different from you,’ said Ring. “That was what was said.” You might argue – with some credibility – that learning what was said by the two men removes some of the force of the photograph; that if you remained in ignorance you’d be free to project your own hypothetical dialogue on the freeze-frame meeting of the two men. But nothing trumps actuality. The exchange carries a double authenticity: the pungency of slagging from one corner and the weariness of riposte from the other. Dan Barrett just wanted to set the record straight. “I’d heard people say ‘it will never be known’ and so on,” he says.“I thought it was no harm to let people know.” No harm at all" Origins ; Co Limerick Dimensions : 31cm x 25cm 1kgBorn in Castleconnell, County Limerick,Mick Mackey first arrived on the inter-county scene at the age of seventeen when he first linked up with the Limerick minor team, before later lining out with the junior side. He made his senior debut in the 1930–31 National League. Mackey went on to play a key part for Limerick during a golden age for the team, and won three All-Ireland medals, five Munster medals and five National Hurling League medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on two occasions, Mackey also captained the team to two All-Ireland victories. His brother, John Mackey, also shared in these victories while his father, "Tyler" Mackey was a one-time All-Ireland runner-up with Limerick. Mackey represented the Munster inter-provincial team for twelve years, winning eight Railway Cup medals during that period. At club level he won fifteen championship medals with Ahane. Throughout his inter-county career, Mackey made 42 championship appearances for Limerick. His retirement came following the conclusion of the 1947 championship. In retirement from playing, Mackey became involved in team management and coaching. As trainer of the Limerick senior team in 1955, he guided them to Munster victory. He also served as a selector on various occasions with both Limerick and Munster. Mackey also served as a referee. Mackey is widely regarded as one of the greatest hurlers in the history of the game. He was the inaugural recipient of the All-Time All-Star Award. He has been repeatedly voted onto teams made up of the sport's greats, including at centre-forward on the Hurling Team of the Centuryin 1984 and the Hurling Team of the Millennium in 2000. Origins : Co Limerick Dimensions : 28cm x 37cm 1kg

25cm x 20cm Abbeyfeale Co Limerick Nice souvenir of the iconic photograph taken by Justin Nelson.The following explanation of the actual verbal exchange between the two legends comes from Michael Moynihan of the Examiner newspaper. "When Christy Ring left the field of play injured in the 1957 Munster championship game between Cork and Waterford at Limerick, he strolled behind the goal, where he passed Mick Mackey, who was acting as umpire for the game. The two exchanged a few words as Ring made his way to the dressing-room.It was an encounter that would have been long forgotten if not for the photograph snapped at precisely the moment the two men met. The picture freezes the moment forever: Mackey, though long retired, still vigorous, still dark haired, somehow incongruous in his umpire’s white coat, clearly hopping a ball; Ring at his fighting weight, his right wrist strapped, caught in the typical pose of a man fielding a remark coming over his shoulder and returning it with interest. Two hurling eras intersect in the two men’s encounter: Limerick’s glory of the 30s, and Ring’s dominance of two subsequent decades.But nobody recorded what was said, and the mystery has echoed down the decades.But Dan Barrett has the answer.He forged a friendship with Ring from the usual raw materials. They had girls the same age, they both worked for oil companies, they didn’t live that far away from each other. And they had hurling in common.We often chatted away at home about hurling,” says Barrett. “In general he wouldn’t criticise players, although he did say about one player for Cork, ‘if you put a whistle on the ball he might hear it’.” Barrett saw Ring’s awareness of his whereabouts at first hand; even in the heat of a game he was conscious of every factor in his surroundings. “We went up to see him one time in Thurles,” says Barrett. “Don’t forget, people would come from all over the country to see a game just for Ring, and the place was packed to the rafters – all along the sideline people were spilling in on the field. “He came out to take a sideline cut at one stage and we were all roaring at him – ‘Go on Ring’, the usual – and he looked up into the crowd, the blue eyes, and he looked right at me. “The following day in work he called in and we were having a chat, and I said ‘if you caught that sideline yesterday, you’d have driven it up to the Devil’s Bit.’ “There was another chap there who said about me, ‘With all his talk he probably wasn’t there at all’. ‘He was there alright,’ said Ring. ‘He was over in the corner of the stand’. He picked me out in the crowd.” “He told me there was no way he’d come on the team as a sub. I remember then when Cork beat Tipperary in the Munster championship for the first time in a long time, there was a helicopter landed near the ground, the Cork crowd were saying ‘here’s Ring’ to rise the Tipp crowd. “I saw his last goal, for the Glen against Blackrock. He collided with a Blackrock man and he took his shot, it wasn’t a hard one, but the keeper put his hurley down and it hopped over his stick.” There were tough days against Tipperary – Ring took off his shirt one Monday to show his friends the bruising across his back from one Tipp defender who had a special knack of letting the Corkman out ahead in order to punish him with his stick. But Ring added that when a disagreement at a Railway Cup game with Leinster became physical, all of Tipperary piled in to back him up. One evening the talk turned to the photograph. Barrett packed the audience – “I had my wife there as a witness,” – and asked Ring the burning question: what had Mackey said to him? “’You didn’t get half enough of it’, said Mackey. ‘I’d expect nothing different from you,’ said Ring. “That was what was said.” You might argue – with some credibility – that learning what was said by the two men removes some of the force of the photograph; that if you remained in ignorance you’d be free to project your own hypothetical dialogue on the freeze-frame meeting of the two men. But nothing trumps actuality. The exchange carries a double authenticity: the pungency of slagging from one corner and the weariness of riposte from the other. Dan Barrett just wanted to set the record straight. “I’d heard people say ‘it will never be known’ and so on,” he says.“I thought it was no harm to let people know.” No harm at all" Origins ; Co Limerick Dimensions : 31cm x 25cm 1kgBorn in Castleconnell, County Limerick,Mick Mackey first arrived on the inter-county scene at the age of seventeen when he first linked up with the Limerick minor team, before later lining out with the junior side. He made his senior debut in the 1930–31 National League. Mackey went on to play a key part for Limerick during a golden age for the team, and won three All-Ireland medals, five Munster medals and five National Hurling League medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on two occasions, Mackey also captained the team to two All-Ireland victories. His brother, John Mackey, also shared in these victories while his father, "Tyler" Mackey was a one-time All-Ireland runner-up with Limerick. Mackey represented the Munster inter-provincial team for twelve years, winning eight Railway Cup medals during that period. At club level he won fifteen championship medals with Ahane. Throughout his inter-county career, Mackey made 42 championship appearances for Limerick. His retirement came following the conclusion of the 1947 championship. In retirement from playing, Mackey became involved in team management and coaching. As trainer of the Limerick senior team in 1955, he guided them to Munster victory. He also served as a selector on various occasions with both Limerick and Munster. Mackey also served as a referee. Mackey is widely regarded as one of the greatest hurlers in the history of the game. He was the inaugural recipient of the All-Time All-Star Award. He has been repeatedly voted onto teams made up of the sport's greats, including at centre-forward on the Hurling Team of the Centuryin 1984 and the Hurling Team of the Millennium in 2000. Origins : Co Limerick Dimensions : 28cm x 37cm 1kg -

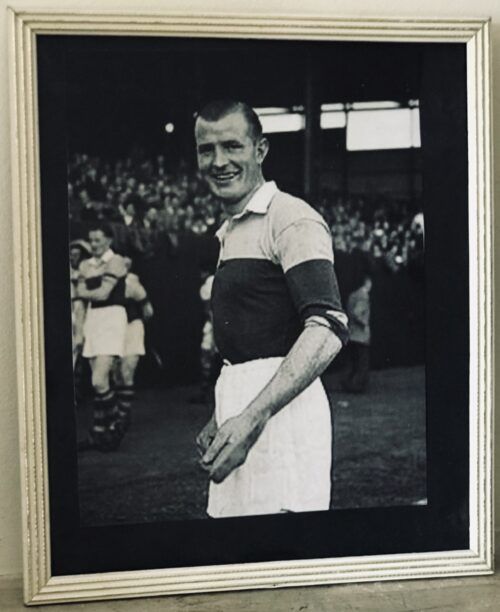

Poignant portrait of all time Wexford Hurling Great Nicky Rackard Enniscorthy Co Wexford 35cm x32cm "I was lucky enough to be on a Wexford team that he was involved with," recalled Liam Griffin. "He put his hand on my shoulder and that was like the hand of God touching you. "He was a fantastic man and his presence was just unbelievable. To see him standing there in a dressing-room, you wouldn't be worried about going out on the pitch, you'd just be looking at him." Despite his many years of service to Wexford GAA, Nicky Rackard's life was cut tragically short and at only the age of 53, the legendary hurler passed on after a battle with cancer. As Liam Griffin recalled on OTB AM, Rackard had also had his struggles with alcohol. "He was a gentleman as well, but look, he had his problems when he wasn't a gentleman as well when he had drink taken like most people," he explained. "But look, he was an inspiration too because he went on to do great work for alcoholics and so forth. "But I'm just going to say this, and I'm not saying this to be smart but because I mean it sincerely. After the All-Ireland final when we won it we put the cup in the middle of the floor the next morning after the All-Ireland. "In my view, he'd had such an influence on me and what we were that we stood around the cup and said a few prayers, and I'm not ashamed to say that I can tell you. "I warned them, and I meant it because I had thought about it in the previous weeks and months before, about any of them becoming an alcoholic, like Nicky Rackard. "He was one of the greatest but hero-worship is dangerous and when they walked out that door their lives would change forever. Nicky's life was spoiled by the worship he received and that's an unintended consequence, but it is the truth." The prominent figure upon Wexford's Mt Rushmore in Liam Griffin's opinion, whatever of Nicky Rackard's troubles in life, Griffin believes his legacy as a hurler is unsurpassed. "He led Wexford when we hadn't fields of barley let me tell you, we had pretty barren fields," he recalled. "Nicky Rackard carried on through a lot of thick and thin with Wexford, through a lot of heartache but he eventually put his flag on the top of the mountain. "He's #1 in Wexford, that's for sure."

Poignant portrait of all time Wexford Hurling Great Nicky Rackard Enniscorthy Co Wexford 35cm x32cm "I was lucky enough to be on a Wexford team that he was involved with," recalled Liam Griffin. "He put his hand on my shoulder and that was like the hand of God touching you. "He was a fantastic man and his presence was just unbelievable. To see him standing there in a dressing-room, you wouldn't be worried about going out on the pitch, you'd just be looking at him." Despite his many years of service to Wexford GAA, Nicky Rackard's life was cut tragically short and at only the age of 53, the legendary hurler passed on after a battle with cancer. As Liam Griffin recalled on OTB AM, Rackard had also had his struggles with alcohol. "He was a gentleman as well, but look, he had his problems when he wasn't a gentleman as well when he had drink taken like most people," he explained. "But look, he was an inspiration too because he went on to do great work for alcoholics and so forth. "But I'm just going to say this, and I'm not saying this to be smart but because I mean it sincerely. After the All-Ireland final when we won it we put the cup in the middle of the floor the next morning after the All-Ireland. "In my view, he'd had such an influence on me and what we were that we stood around the cup and said a few prayers, and I'm not ashamed to say that I can tell you. "I warned them, and I meant it because I had thought about it in the previous weeks and months before, about any of them becoming an alcoholic, like Nicky Rackard. "He was one of the greatest but hero-worship is dangerous and when they walked out that door their lives would change forever. Nicky's life was spoiled by the worship he received and that's an unintended consequence, but it is the truth." The prominent figure upon Wexford's Mt Rushmore in Liam Griffin's opinion, whatever of Nicky Rackard's troubles in life, Griffin believes his legacy as a hurler is unsurpassed. "He led Wexford when we hadn't fields of barley let me tell you, we had pretty barren fields," he recalled. "Nicky Rackard carried on through a lot of thick and thin with Wexford, through a lot of heartache but he eventually put his flag on the top of the mountain. "He's #1 in Wexford, that's for sure." -

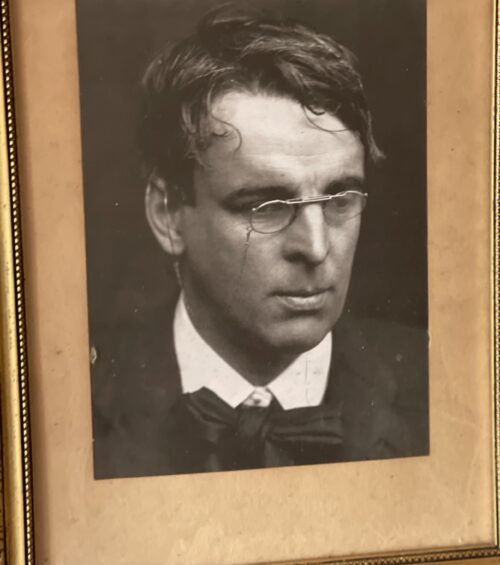

40cm x 30cm Enniscrone Co Sligo William Butler Yeats(13 June 1865 – 28 January 1939) Irish poet, dramatist, prose writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. A pillar of the Irish literary establishment, he helped to found the Abbey Theatre, and in his later years served two terms as a Senator of the Irish Free State. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival along with Lady Gregory, Edward Martyn and others. Yeats was born in Sandymount, Ireland, and educated there and in London. He was a Protestant and member of the Anglo-Irish community. He spent childhood holidays in County Sligo and studied poetry from an early age, when he became fascinated by Irish legends and the occult. These topics feature in the first phase of his work, which lasted roughly until the turn of the 20th century. His earliest volume of verse was published in 1889, and its slow-paced and lyrical poems display debts to Edmund Spenser, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the poets of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. From 1900, his poetry grew more physical and realistic. He largely renounced the transcendental beliefs of his youth, though he remained preoccupied with physical and spiritual masks, as well as with cyclical theories of life. In 1923, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

40cm x 30cm Enniscrone Co Sligo William Butler Yeats(13 June 1865 – 28 January 1939) Irish poet, dramatist, prose writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. A pillar of the Irish literary establishment, he helped to found the Abbey Theatre, and in his later years served two terms as a Senator of the Irish Free State. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival along with Lady Gregory, Edward Martyn and others. Yeats was born in Sandymount, Ireland, and educated there and in London. He was a Protestant and member of the Anglo-Irish community. He spent childhood holidays in County Sligo and studied poetry from an early age, when he became fascinated by Irish legends and the occult. These topics feature in the first phase of his work, which lasted roughly until the turn of the 20th century. His earliest volume of verse was published in 1889, and its slow-paced and lyrical poems display debts to Edmund Spenser, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the poets of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. From 1900, his poetry grew more physical and realistic. He largely renounced the transcendental beliefs of his youth, though he remained preoccupied with physical and spiritual masks, as well as with cyclical theories of life. In 1923, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. -

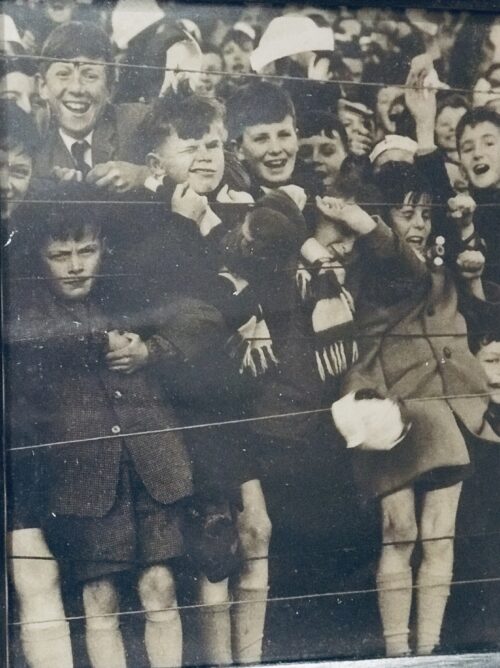

Fantastic piece of Tipperary Hurling Nostalgia here as we see a very young Jimmy Doyle being presented with a Thurles Schoolboys Streel League Trophy. 45cm x 35cm. Thurles Co Tipperary "Jimmy Doyle would have seen many things, and watched a lot of hurling, in his 76 years. But the Tipperary legend, who died last Monday, was possibly most pleased to watch the sumptuous performance of his native county, against Limerick, just the day before. Simply put, the way Tipp hurl at the moment is pure Jimmy Doyle - and no finer compliment can be paid in the Premier County. Eamon O'Shea's current group are all about skill, vision, élan, creativity, elegance: the very things which defined Doyle's playing style as he terrorised defences for close on two decades. Indeed, it's a funny irony that the Thurles Sarsfields icon, were he young today, would easily slip into the modern game, such was his impeccable technique, flair and positional sense. There may have been "better" hurlers in history (Cork's Christy Ring surely still stands as the greatest of all). There may even have been better Tipp hurlers - John Doyle, for example, who won more All-Irelands than his namesake. But there was hardly a more naturally gifted man to play in 125 years. The hurling of Doyle's heyday, by contrast with today, was rough, tough, sometimes brutal. His own Tipp team featured a full-back line so feared for taking no prisoners, they were christened (not entirely unaffectionately) "Hell's Kitchen". While not quite unique, Doyle was one of a select group back then who relied less on brute force, and more on quick wrists, "sixth sense" spatial awareness, and uncanny eye-hand co-ordination to overcome. During the 1950s and '60s, when he was in his pomp, forwards were battered, bruised and banjaxed, with little protection from rules or referees. It speaks even more highly, then, of this small, slim man ("no bigger in stature than a jockey", as put by Irish Independent sportswriter Vincent Hogan) that he should achieve such greatness. What, you'd wonder, might have been his limitations - if any - had he played in the modern game? Regardless, his place in hurling's pantheon is assured; one of a handful of players to transcend even greatness and enter some almost supernatural realm of brilliance. This week his former teammate, and fellow Tipp legend, Michael "Babs" Keating recalled how Christy Ring had once told him, "If Jimmy Doyle was as strong as you and I, nobody would ever ask who was the best." Like Ring, Jimmy made both the 1984 hurling Team of the Century, compiled in honour of the GAA's Centenary, and the later Team of the Millennium. We can also throw in a slot on both Tipperary and Munster Teams of the Millennium, and being named Hurler of the Year in 1965 - and that's just the start of one of the most glittering collections of honours in hurling history.

Fantastic piece of Tipperary Hurling Nostalgia here as we see a very young Jimmy Doyle being presented with a Thurles Schoolboys Streel League Trophy. 45cm x 35cm. Thurles Co Tipperary "Jimmy Doyle would have seen many things, and watched a lot of hurling, in his 76 years. But the Tipperary legend, who died last Monday, was possibly most pleased to watch the sumptuous performance of his native county, against Limerick, just the day before. Simply put, the way Tipp hurl at the moment is pure Jimmy Doyle - and no finer compliment can be paid in the Premier County. Eamon O'Shea's current group are all about skill, vision, élan, creativity, elegance: the very things which defined Doyle's playing style as he terrorised defences for close on two decades. Indeed, it's a funny irony that the Thurles Sarsfields icon, were he young today, would easily slip into the modern game, such was his impeccable technique, flair and positional sense. There may have been "better" hurlers in history (Cork's Christy Ring surely still stands as the greatest of all). There may even have been better Tipp hurlers - John Doyle, for example, who won more All-Irelands than his namesake. But there was hardly a more naturally gifted man to play in 125 years. The hurling of Doyle's heyday, by contrast with today, was rough, tough, sometimes brutal. His own Tipp team featured a full-back line so feared for taking no prisoners, they were christened (not entirely unaffectionately) "Hell's Kitchen". While not quite unique, Doyle was one of a select group back then who relied less on brute force, and more on quick wrists, "sixth sense" spatial awareness, and uncanny eye-hand co-ordination to overcome. During the 1950s and '60s, when he was in his pomp, forwards were battered, bruised and banjaxed, with little protection from rules or referees. It speaks even more highly, then, of this small, slim man ("no bigger in stature than a jockey", as put by Irish Independent sportswriter Vincent Hogan) that he should achieve such greatness. What, you'd wonder, might have been his limitations - if any - had he played in the modern game? Regardless, his place in hurling's pantheon is assured; one of a handful of players to transcend even greatness and enter some almost supernatural realm of brilliance. This week his former teammate, and fellow Tipp legend, Michael "Babs" Keating recalled how Christy Ring had once told him, "If Jimmy Doyle was as strong as you and I, nobody would ever ask who was the best." Like Ring, Jimmy made both the 1984 hurling Team of the Century, compiled in honour of the GAA's Centenary, and the later Team of the Millennium. We can also throw in a slot on both Tipperary and Munster Teams of the Millennium, and being named Hurler of the Year in 1965 - and that's just the start of one of the most glittering collections of honours in hurling history. -

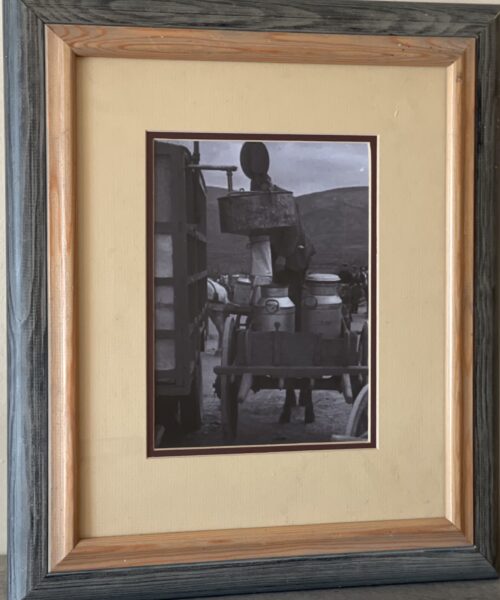

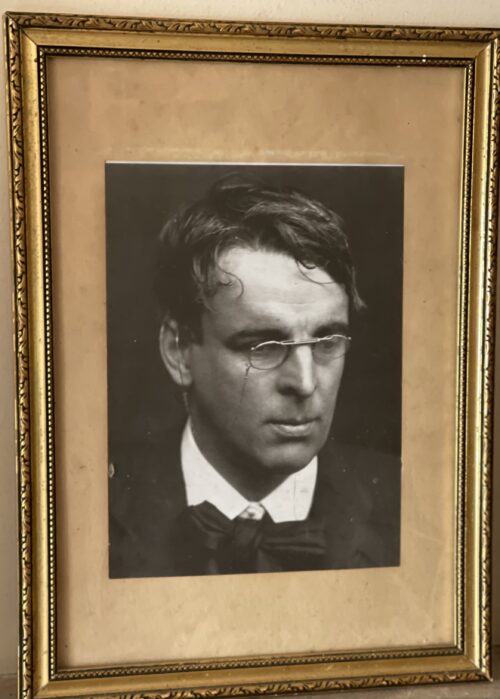

Beautifully mounted & framed 30cm x 30cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

Beautifully mounted & framed 30cm x 30cm Dublin Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

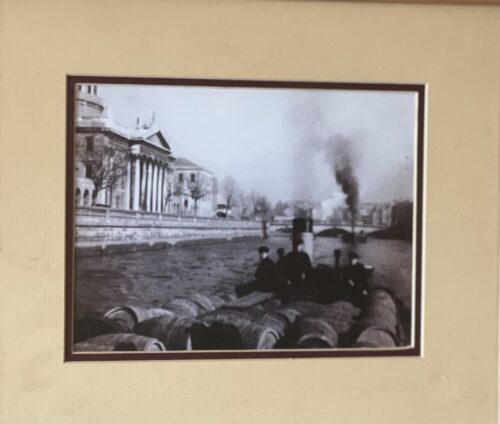

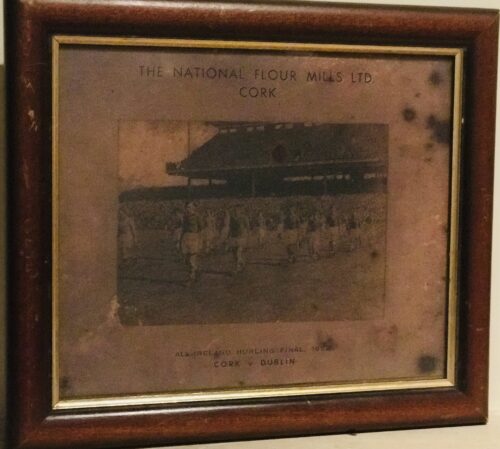

Beautifully atmospheric lithograph of the pre match parade by the Cork and Dublin Hurlers in 1952.This lithograph was sponsored by the National Flour Mills Co.Ltd. 42cm x 46cm Douglas Cork

Beautifully atmospheric lithograph of the pre match parade by the Cork and Dublin Hurlers in 1952.This lithograph was sponsored by the National Flour Mills Co.Ltd. 42cm x 46cm Douglas Cork

The 1952 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final was the 65th All-Ireland Final and the culmination of the 1952 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship, an inter-county hurling tournament for the top teams in Ireland. The match was held at Croke Park, Dublin, on 7 September 1952, between Cork and Dublin. The Leinster champions lost to their Munster opponents on a score line of 2-14 to 0-7.1952 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Final

Event 1952 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Cork Dublin 2-14 0-7 Date 7 September 1952 Venue Croke Park, Dublin Referee W. O'Donoghue (Limerick) Attendance 71,195 Origins : Co CorkDimensions : 31cm x 36cm 1.5kg -

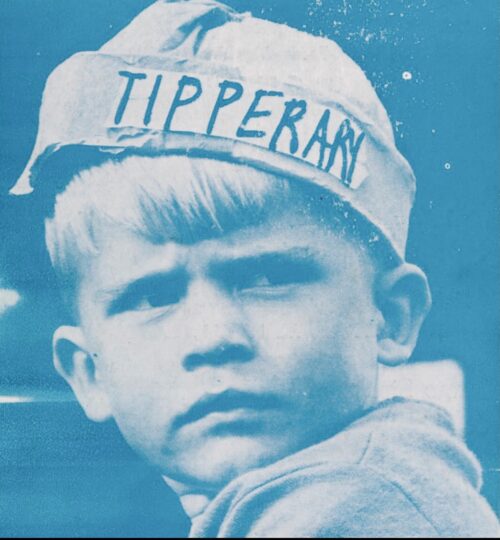

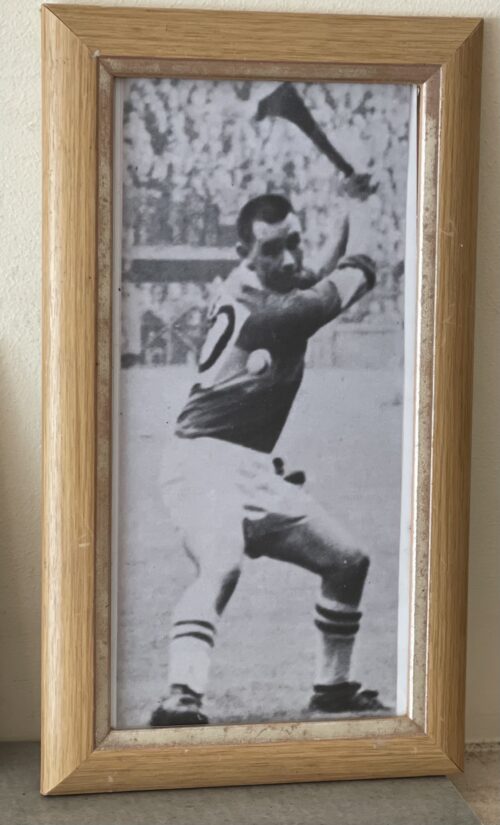

20cm x 35cm. Thurles Co Tipperary "Jimmy Doyle would have seen many things, and watched a lot of hurling, in his 76 years. But the Tipperary legend, who died last Monday, was possibly most pleased to watch the sumptuous performance of his native county, against Limerick, just the day before. Simply put, the way Tipp hurl at the moment is pure Jimmy Doyle - and no finer compliment can be paid in the Premier County. Eamon O'Shea's current group are all about skill, vision, élan, creativity, elegance: the very things which defined Doyle's playing style as he terrorised defences for close on two decades. Indeed, it's a funny irony that the Thurles Sarsfields icon, were he young today, would easily slip into the modern game, such was his impeccable technique, flair and positional sense. There may have been "better" hurlers in history (Cork's Christy Ring surely still stands as the greatest of all). There may even have been better Tipp hurlers - John Doyle, for example, who won more All-Irelands than his namesake. But there was hardly a more naturally gifted man to play in 125 years. The hurling of Doyle's heyday, by contrast with today, was rough, tough, sometimes brutal. His own Tipp team featured a full-back line so feared for taking no prisoners, they were christened (not entirely unaffectionately) "Hell's Kitchen". While not quite unique, Doyle was one of a select group back then who relied less on brute force, and more on quick wrists, "sixth sense" spatial awareness, and uncanny eye-hand co-ordination to overcome. During the 1950s and '60s, when he was in his pomp, forwards were battered, bruised and banjaxed, with little protection from rules or referees. It speaks even more highly, then, of this small, slim man ("no bigger in stature than a jockey", as put by Irish Independent sportswriter Vincent Hogan) that he should achieve such greatness. What, you'd wonder, might have been his limitations - if any - had he played in the modern game? Regardless, his place in hurling's pantheon is assured; one of a handful of players to transcend even greatness and enter some almost supernatural realm of brilliance. This week his former teammate, and fellow Tipp legend, Michael "Babs" Keating recalled how Christy Ring had once told him, "If Jimmy Doyle was as strong as you and I, nobody would ever ask who was the best." Like Ring, Jimmy made both the 1984 hurling Team of the Century, compiled in honour of the GAA's Centenary, and the later Team of the Millennium. We can also throw in a slot on both Tipperary and Munster Teams of the Millennium, and being named Hurler of the Year in 1965 - and that's just the start of one of the most glittering collections of honours in hurling history.

20cm x 35cm. Thurles Co Tipperary "Jimmy Doyle would have seen many things, and watched a lot of hurling, in his 76 years. But the Tipperary legend, who died last Monday, was possibly most pleased to watch the sumptuous performance of his native county, against Limerick, just the day before. Simply put, the way Tipp hurl at the moment is pure Jimmy Doyle - and no finer compliment can be paid in the Premier County. Eamon O'Shea's current group are all about skill, vision, élan, creativity, elegance: the very things which defined Doyle's playing style as he terrorised defences for close on two decades. Indeed, it's a funny irony that the Thurles Sarsfields icon, were he young today, would easily slip into the modern game, such was his impeccable technique, flair and positional sense. There may have been "better" hurlers in history (Cork's Christy Ring surely still stands as the greatest of all). There may even have been better Tipp hurlers - John Doyle, for example, who won more All-Irelands than his namesake. But there was hardly a more naturally gifted man to play in 125 years. The hurling of Doyle's heyday, by contrast with today, was rough, tough, sometimes brutal. His own Tipp team featured a full-back line so feared for taking no prisoners, they were christened (not entirely unaffectionately) "Hell's Kitchen". While not quite unique, Doyle was one of a select group back then who relied less on brute force, and more on quick wrists, "sixth sense" spatial awareness, and uncanny eye-hand co-ordination to overcome. During the 1950s and '60s, when he was in his pomp, forwards were battered, bruised and banjaxed, with little protection from rules or referees. It speaks even more highly, then, of this small, slim man ("no bigger in stature than a jockey", as put by Irish Independent sportswriter Vincent Hogan) that he should achieve such greatness. What, you'd wonder, might have been his limitations - if any - had he played in the modern game? Regardless, his place in hurling's pantheon is assured; one of a handful of players to transcend even greatness and enter some almost supernatural realm of brilliance. This week his former teammate, and fellow Tipp legend, Michael "Babs" Keating recalled how Christy Ring had once told him, "If Jimmy Doyle was as strong as you and I, nobody would ever ask who was the best." Like Ring, Jimmy made both the 1984 hurling Team of the Century, compiled in honour of the GAA's Centenary, and the later Team of the Millennium. We can also throw in a slot on both Tipperary and Munster Teams of the Millennium, and being named Hurler of the Year in 1965 - and that's just the start of one of the most glittering collections of honours in hurling history. -

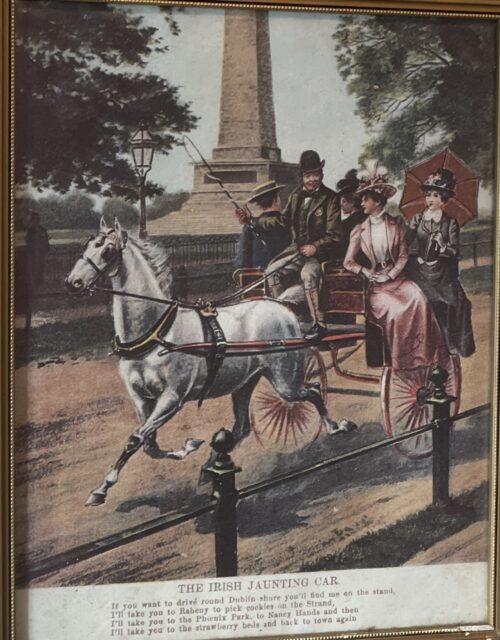

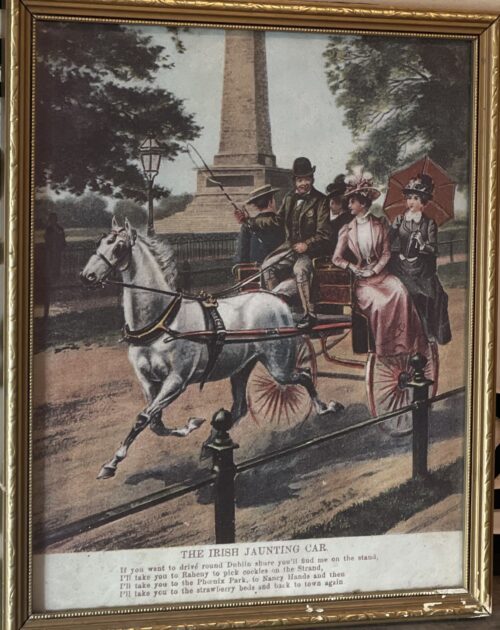

58cm x 42cm Quaint vintage poster of a jaunting car carrying a group around Phoenix Park- the giant Wellington monument can be seen in the background. The Wellington Monument or sometimes the Wellington Testimonial,is an obelisk located in the Phoenix Park, Dublin, Ireland. The testimonial is situated at the southeast end of the Park, overlooking Kilmainham and the River Liffey. The structure is 62 metres (203 ft) tall, making it the largest obelisk in Europe

58cm x 42cm Quaint vintage poster of a jaunting car carrying a group around Phoenix Park- the giant Wellington monument can be seen in the background. The Wellington Monument or sometimes the Wellington Testimonial,is an obelisk located in the Phoenix Park, Dublin, Ireland. The testimonial is situated at the southeast end of the Park, overlooking Kilmainham and the River Liffey. The structure is 62 metres (203 ft) tall, making it the largest obelisk in EuropeHistory

The Wellington Testimonial was built to commemorate the victories of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington. Wellington, the British politician and general, also known as the 'Iron Duke', was born in Ireland. Originally planned to be located in Merrion Square, it was built in the Phoenix Park after opposition from the square's residents. The obelisk was designed by the architect Sir Robert Smirke and the foundation stone was laid in 1817. In 1820, the project ran out of construction funds and the structure remained unfinished until 18 June 1861 when it was opened to the public. There were also plans for a statue of Wellington on horseback, but a shortage of funds ruled that out.Features

There are four bronze plaques cast from cannons captured at Waterloo – three of which have pictorial representations of his career while the fourth has an inscription. The plaques depict 'Civil and Religious Liberty' by John Hogan, 'Waterloo' by Thomas Farrell and the 'Indian Wars' by Joseph Robinson Kirk. The inscription reads:- Asia and Europe, saved by thee, proclaim

- Invincible in war thy deathless name,

- Now round thy brow the civic oak we twine

- That every earthly glory may be thine.

Cultural references

The monument is referenced throughout James Joyce's Finnegans Wake. The first page of the novel alludes to a giant whose head is at "Howth Castle and Environs" and whose toes are at "a knock out in the park (p. 3)"; John Bishop extends the analogy, interpreting this centrally located obelisk as the prone giant's male member. A few pages later, the monument is the site of the fictional "Willingdone Museyroom" (p. 8).