-

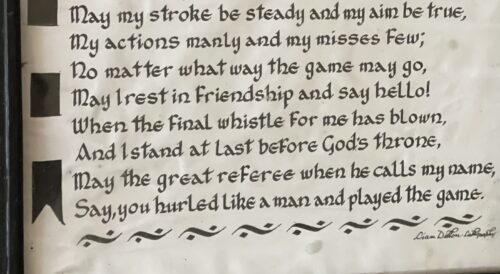

42cm x 32cm. Dublin Lovely collection of the once ubiquitous Wills Cigarettes collector cards depicting notable Irish Rugby players of the early part of the 20th Century such as G.V Stephenson,G.R Beamish and J.L Farrell. W.D. & H.O. Wills was a British tobacco importer and manufacturer formed in Bristol, England. It was the first UK company to mass-produce cigarettes. It was one of the founding companies of Imperial Tobacco along with John Player & Sons. The company was founded in 1786 and went by various names before 1830 when it became W.D. & H.O. Wills. Tobacco was processed and sold under several brand names, some of which were still used by Imperial Tobacco until the second half of the 20th century. The company pioneered the use of cigarette cards within their packaging. Many of the buildings in Bristol and other cities around the United Kingdom still exist with several being converted to residential use. Henry Overton Wills I arrived in Bristol in 1786 from Salisbury, and opened a tobacco shop on Castle Street with his partner Samuel Watkins. They named their firm Wills, Watkins & Co. When Watkins retired in 1789, the firm became Wills & Co. Next, the company was known from 1791 to 1793 as Lilly, Wills & Co, when it merged with the firm of Peter Lilly, who owned a snuff mill on the Land Yeo at Barrow Gurney. The company then was known from 1793 up until Lilly's' retirement in 1803 as Lilly and Wills. In 1826 H.O. Wills's sons William Day Wills and Henry Overton Wills II took over the company, which in 1830 became W.D. & H.O. Wills. William Day Wills' middle name is from his mother Anne Day of Bristol. Both W.D. and H.O. Wills were non-smokers. When William Day Wills was killed in 1865 in a carriage accident, 2000 people attended his funeral at Arnos Vale Cemetery.During the 1860s a new factory was built to replace the original Redcliffe Street premises, but they quickly outgrew this. The East Street factory of W.D. & H.O. Wills in Bedminster opened in 1886 with a high tea for the 900 employees in the Cigar Room. The new factory was expected to meet their needs for the remainder of the century, but within a decade it was doubled in size and early in the 1900s a further Bristol factory was created in Raleigh Road, Southville. This growth was largely due to the success of cigarettes. Their first brand was "Bristol", made at the London factory from 1871 to 1974. Three Castles and Gold Flake followed in 1878 but the greatest success was the machine-made Woodbine ten years later. Embassy was introduced in 1914 and relaunched in 1962 with coupons. Other popular brands included Capstan and Passing Clouds. The company also made cigar brands like Castella and Whiffs, several pipe tobacco brands and Golden Virginia hand-rolling tobacco. Up until 1920 only women and girls were employed as cigar-makers. One clause in the women's contract stipulated:

42cm x 32cm. Dublin Lovely collection of the once ubiquitous Wills Cigarettes collector cards depicting notable Irish Rugby players of the early part of the 20th Century such as G.V Stephenson,G.R Beamish and J.L Farrell. W.D. & H.O. Wills was a British tobacco importer and manufacturer formed in Bristol, England. It was the first UK company to mass-produce cigarettes. It was one of the founding companies of Imperial Tobacco along with John Player & Sons. The company was founded in 1786 and went by various names before 1830 when it became W.D. & H.O. Wills. Tobacco was processed and sold under several brand names, some of which were still used by Imperial Tobacco until the second half of the 20th century. The company pioneered the use of cigarette cards within their packaging. Many of the buildings in Bristol and other cities around the United Kingdom still exist with several being converted to residential use. Henry Overton Wills I arrived in Bristol in 1786 from Salisbury, and opened a tobacco shop on Castle Street with his partner Samuel Watkins. They named their firm Wills, Watkins & Co. When Watkins retired in 1789, the firm became Wills & Co. Next, the company was known from 1791 to 1793 as Lilly, Wills & Co, when it merged with the firm of Peter Lilly, who owned a snuff mill on the Land Yeo at Barrow Gurney. The company then was known from 1793 up until Lilly's' retirement in 1803 as Lilly and Wills. In 1826 H.O. Wills's sons William Day Wills and Henry Overton Wills II took over the company, which in 1830 became W.D. & H.O. Wills. William Day Wills' middle name is from his mother Anne Day of Bristol. Both W.D. and H.O. Wills were non-smokers. When William Day Wills was killed in 1865 in a carriage accident, 2000 people attended his funeral at Arnos Vale Cemetery.During the 1860s a new factory was built to replace the original Redcliffe Street premises, but they quickly outgrew this. The East Street factory of W.D. & H.O. Wills in Bedminster opened in 1886 with a high tea for the 900 employees in the Cigar Room. The new factory was expected to meet their needs for the remainder of the century, but within a decade it was doubled in size and early in the 1900s a further Bristol factory was created in Raleigh Road, Southville. This growth was largely due to the success of cigarettes. Their first brand was "Bristol", made at the London factory from 1871 to 1974. Three Castles and Gold Flake followed in 1878 but the greatest success was the machine-made Woodbine ten years later. Embassy was introduced in 1914 and relaunched in 1962 with coupons. Other popular brands included Capstan and Passing Clouds. The company also made cigar brands like Castella and Whiffs, several pipe tobacco brands and Golden Virginia hand-rolling tobacco. Up until 1920 only women and girls were employed as cigar-makers. One clause in the women's contract stipulated: The Wills Building in Newcastle upon Tyne, a former W.D. & H.O. Wills factoryIn 1898 Henry Herbert Wills visited Australia which led to the establishment of W.D. & H.O. Wills (Australia) Ltd. in 1900.When Princess Elizabeth visited on 3 March 1950 she was given cigarette cards as a gift for Prince Charles. In 1901 thirteen British tobacco companies discussed the American Tobacco Company building a factory in the UK to bypass taxes. The Imperial Tobacco Company was incorporated on 10 December 1901 with seven of the directors being members of the Wills family. Imperial remains one of the world's largest tobacco companies.

The Wills Building in Newcastle upon Tyne, a former W.D. & H.O. Wills factoryIn 1898 Henry Herbert Wills visited Australia which led to the establishment of W.D. & H.O. Wills (Australia) Ltd. in 1900.When Princess Elizabeth visited on 3 March 1950 she was given cigarette cards as a gift for Prince Charles. In 1901 thirteen British tobacco companies discussed the American Tobacco Company building a factory in the UK to bypass taxes. The Imperial Tobacco Company was incorporated on 10 December 1901 with seven of the directors being members of the Wills family. Imperial remains one of the world's largest tobacco companies. The former W.D. & H.O. warehouse building in Perth, Western AustraliaThe last member of the Wills family to serve the company was Christopher, the great great grandson of H.O. Wills I. He retired as sales research manager in 1969. The company had factories and offices not only in Bristol, but also in Swindon, Dublin, Newcastle and Glasgow. The largest cigarette factory in Europe was opened at Hartcliffe Bristol, and was designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in 1974, but closed in 1990. It proved impossible to find a new use for it and it was demolished in 1999; its site is now the Imperial Park retail complex, but the associated offices became Lakeshore, residential apartments created by Urban Splash. The facade of the large factory in Bedminster and bonded warehouses at Cumberland Basin remain prominent buildings in Bristol, although much of the existing land and buildings have been converted to other uses, such as The Tobacco Factory Theatre. The Newcastle factory closed in 1986 and stood derelict for over a decade, before the front of the Art Deco building – which was preserved by being Grade II listed – reopened as a block of luxury apartments in 1998. (See main article: Wills Building) The factory in Glasgow has similarly been converted into offices. In 1988 Imperial Tobacco withdrew the Wills brand in the United Kingdom (except for the popular Woodbine and Capstan Full Strength brands, which still carry the name). The company pioneered canteens for the workers, free medical care, sports facilities and paid holidays. Wills commissioned portraits of long-serving employees, several of which are held by Bristol Museum and Art Gallery and some of which can be seen on display at the M Shed museum. In 1893 the W.D. & H.O. Wills Ltd Association Football Team was established and the company also held singing classes for the younger workers and women that year.In 1899 wives of Wills employees serving in the Boer War were granted 10 shillings per week by the factory. Bristol Archives holds extensive records of W.D. & H.O. Wills and Imperial Tobacco . In addition there are photographs of the Newcastle factory of W.D. & H.O. Wills at Tyne and Wear Archives in Bristol holds the Wills Collection of Tobacco Antiquities, consisting of advertising, marketing and packaging samples from the company's history, photographs and artefacts relating to the history of tobacco. In 1959 the company launched the short-lived Strand brand. This was accompanied by the iconic, but commercially disastrous, You're never alone with a Strand television advertisement. In India, the Gold Flake, Classic and Wills Navy Cut range of cigarettes, manufactured by ITC , formerly the Imperial Tobacco Company of India Limited,still has W.D. & H.O. Wills printed on the cigarettes and their packaging. These lines of cigarettes have a dominant market share. In 1887, Wills were one of the first UK tobacco companies to include advertising cards in their packs of cigarettes, but it was not until 1895 that they produced their first general interest set of cards ('Ships and Sailors'). Other Wills sets include 'Aviation' (1910), 'Lucky Charms' (1923), 'British Butterflies' (1927), 'Famous Golfers' (1930), 'Garden Flowers' (1933) and 'Air Raid Precautions' (1938) Wills also released several sports sets, such as the cricket (1901, 1908, 1909, 1910), association football (1902, 1935, 1939), rugby union (1902, 1929) and Australian rules football (1905) series.A Woodbine vending machine, now in the Staffordshire County Museumat Shugborough Hall, England

The former W.D. & H.O. warehouse building in Perth, Western AustraliaThe last member of the Wills family to serve the company was Christopher, the great great grandson of H.O. Wills I. He retired as sales research manager in 1969. The company had factories and offices not only in Bristol, but also in Swindon, Dublin, Newcastle and Glasgow. The largest cigarette factory in Europe was opened at Hartcliffe Bristol, and was designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in 1974, but closed in 1990. It proved impossible to find a new use for it and it was demolished in 1999; its site is now the Imperial Park retail complex, but the associated offices became Lakeshore, residential apartments created by Urban Splash. The facade of the large factory in Bedminster and bonded warehouses at Cumberland Basin remain prominent buildings in Bristol, although much of the existing land and buildings have been converted to other uses, such as The Tobacco Factory Theatre. The Newcastle factory closed in 1986 and stood derelict for over a decade, before the front of the Art Deco building – which was preserved by being Grade II listed – reopened as a block of luxury apartments in 1998. (See main article: Wills Building) The factory in Glasgow has similarly been converted into offices. In 1988 Imperial Tobacco withdrew the Wills brand in the United Kingdom (except for the popular Woodbine and Capstan Full Strength brands, which still carry the name). The company pioneered canteens for the workers, free medical care, sports facilities and paid holidays. Wills commissioned portraits of long-serving employees, several of which are held by Bristol Museum and Art Gallery and some of which can be seen on display at the M Shed museum. In 1893 the W.D. & H.O. Wills Ltd Association Football Team was established and the company also held singing classes for the younger workers and women that year.In 1899 wives of Wills employees serving in the Boer War were granted 10 shillings per week by the factory. Bristol Archives holds extensive records of W.D. & H.O. Wills and Imperial Tobacco . In addition there are photographs of the Newcastle factory of W.D. & H.O. Wills at Tyne and Wear Archives in Bristol holds the Wills Collection of Tobacco Antiquities, consisting of advertising, marketing and packaging samples from the company's history, photographs and artefacts relating to the history of tobacco. In 1959 the company launched the short-lived Strand brand. This was accompanied by the iconic, but commercially disastrous, You're never alone with a Strand television advertisement. In India, the Gold Flake, Classic and Wills Navy Cut range of cigarettes, manufactured by ITC , formerly the Imperial Tobacco Company of India Limited,still has W.D. & H.O. Wills printed on the cigarettes and their packaging. These lines of cigarettes have a dominant market share. In 1887, Wills were one of the first UK tobacco companies to include advertising cards in their packs of cigarettes, but it was not until 1895 that they produced their first general interest set of cards ('Ships and Sailors'). Other Wills sets include 'Aviation' (1910), 'Lucky Charms' (1923), 'British Butterflies' (1927), 'Famous Golfers' (1930), 'Garden Flowers' (1933) and 'Air Raid Precautions' (1938) Wills also released several sports sets, such as the cricket (1901, 1908, 1909, 1910), association football (1902, 1935, 1939), rugby union (1902, 1929) and Australian rules football (1905) series.A Woodbine vending machine, now in the Staffordshire County Museumat Shugborough Hall, England-

Franklin Roosevelt, 1902

-

J.E. Doig of Sunderland, 1902

-

James Dickson of Port Adelaide, 1906

-

S.J. Cagney of Ireland, 1929

-

Stanley Matthews, 1939

-

New Croton Dam, NY The factory in Hartcliffe, Bristol, was the location for the filming of UK television series Doctor Who, Episode 95 - The Sun Makers (1977). Filming at the Wills Factory spanned 13 to 15 June 1977. In addition to the roof and tunnels, scenes were also filmed in the lift and the roof vent.

-

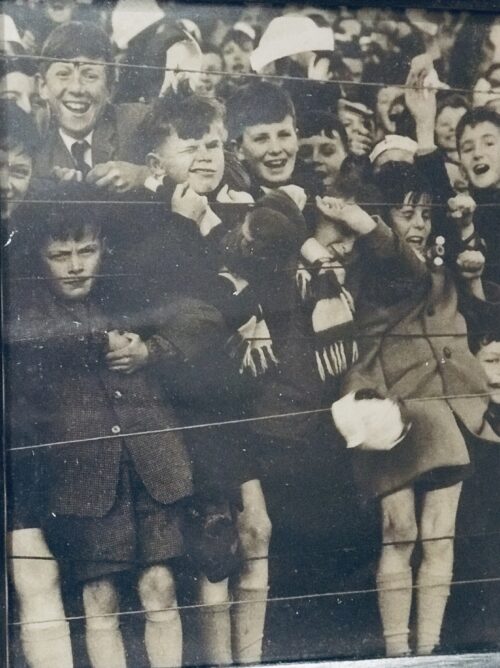

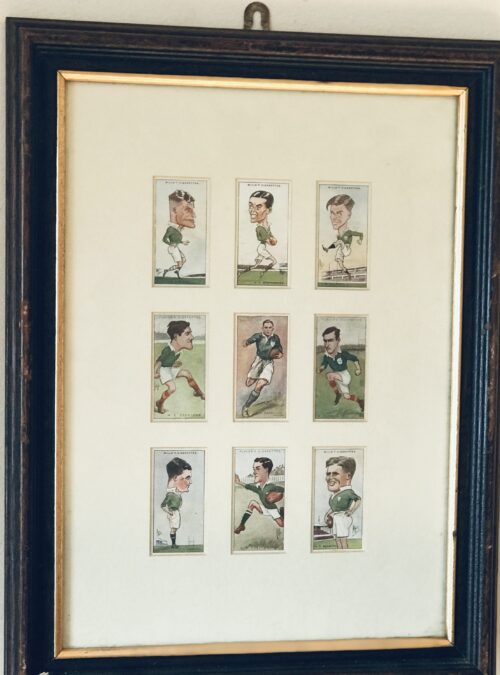

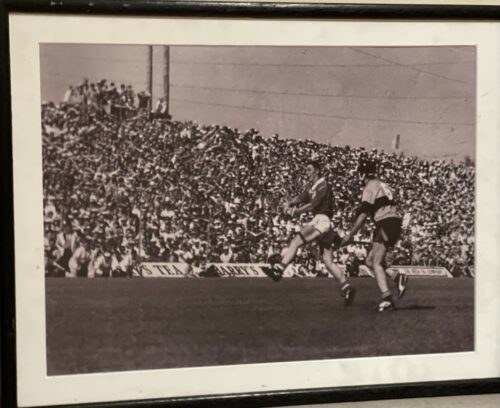

48cm x 39cm. Dublin July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.

48cm x 39cm. Dublin July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.Muhammad Ali's Irish roots explained

The astonishing fact that he had Irish roots, being descended from Abe Grady, an Irishman from Ennis, County Clare, only became known later in life. He returned to Ireland where he had fought and defeated Al “Blue” Lewis in Croke Park in 1972 almost seven years ago in 2009 to help raise money for his non–profit Muhammad Ali Center, a cultural and educational center in Louisville, Kentucky, and other hospices. He was also there to become the first Freeman of the town. The boxing great is no stranger to Irish shores and previously made a famous trip to Ireland in 1972 when he sat down with Cathal O’Shannon of RTE for a fascinating television interview. What’s more, genealogist Antoinette O'Brien discovered that one of Ali’s great-grandfathers emigrated to the United States from County Clare, meaning that the three-time heavyweight world champion joins the likes of President Obama and Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. as prominent African-Americans with Irish heritage. In the 1860s, Abe Grady left Ennis in County Clare to start a new life in America. He would make his home in Kentucky and marry a free African-American woman. The couple started a family, and one of their daughters was Odessa Lee Grady. Odessa met and married Cassius Clay, Sr. and on January 17, 1942, Cassius junior was born. Cassius Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali when he became a Muslim in 1964. Ali, an Olympic gold medalist at the 1960 games in Rome, has been suffering from Parkinson's for some years but was committed to raising funds for his center During his visit to Clare, he was mobbed by tens of thousands of locals who turned out to meet him and show him the area where his great-grandfather came from.Tracing Muhammad Ali's roots back to County Clare

Historian Dick Eastman had traced Ali’s roots back to Abe Grady the Clare emigrant to Kentucky and the freed slave he married. Eastman wrote: “An 1855 land survey of Ennis, a town in County Clare, Ireland, contains a reference to John Grady, who was renting a house in Turnpike Road in the center of the town. His rent payment was fifteen shillings a month. A few years later, his son Abe Grady immigrated to the United States. He settled in Kentucky." Also, around the year 1855, a man and a woman who were both freed slaves, originally from Liberia, purchased land in or around Duck Lick Creek, Logan, Kentucky. The two married, raised a family and farmed the land. These free blacks went by the name, Morehead, the name of white slave owners of the area. Odessa Grady Clay, Cassius Clay's mother, was the great-granddaughter of the freed slave Tom Morehead and of John Grady of Ennis, whose son Abe had emigrated from Ireland to the United States. She named her son Cassius in honor of a famous Kentucky abolitionist of that time. When he changed his name to Muhammad Ali in 1964, the famous boxer remarked, "Why should I keep my white slavemaster name visible and my black ancestors invisible, unknown, unhonored?" Ali was not only the greatest sporting figure, but he was also the best-known person in the world at his height, revered from Africa to Asia and all over the world. To the end, he was a battler, shown rare courage fighting Parkinson’s Disease, and surviving far longer than most sufferers from the disease. -

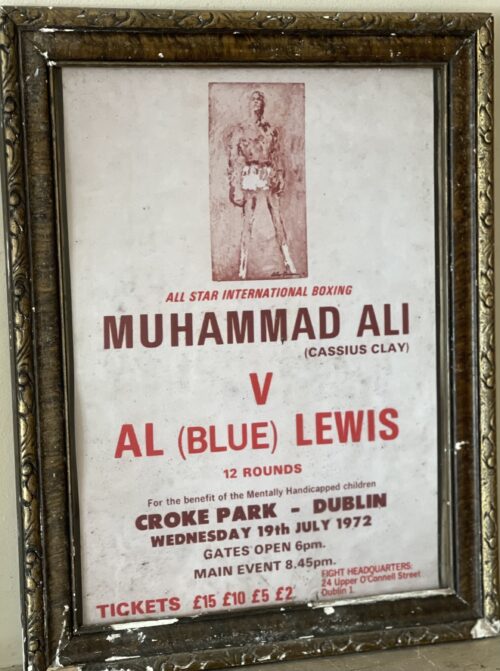

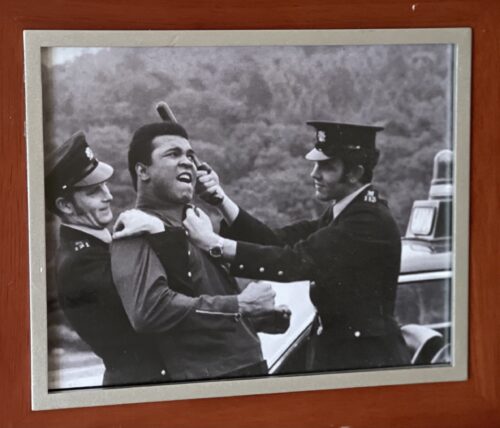

29cm x 36cm. Dublin Famous picture during The Greatest's visit to Ireland of Muhammad Ali play fighting with two members of An Garda Siochana.Some memory for those officers to tell their grandchildren about ! July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.

29cm x 36cm. Dublin Famous picture during The Greatest's visit to Ireland of Muhammad Ali play fighting with two members of An Garda Siochana.Some memory for those officers to tell their grandchildren about ! July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.Muhammad Ali's Irish roots explained

The astonishing fact that he had Irish roots, being descended from Abe Grady, an Irishman from Ennis, County Clare, only became known later in life. He returned to Ireland where he had fought and defeated Al “Blue” Lewis in Croke Park in 1972 almost seven years ago in 2009 to help raise money for his non–profit Muhammad Ali Center, a cultural and educational center in Louisville, Kentucky, and other hospices. He was also there to become the first Freeman of the town. The boxing great is no stranger to Irish shores and previously made a famous trip to Ireland in 1972 when he sat down with Cathal O’Shannon of RTE for a fascinating television interview. What’s more, genealogist Antoinette O'Brien discovered that one of Ali’s great-grandfathers emigrated to the United States from County Clare, meaning that the three-time heavyweight world champion joins the likes of President Obama and Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. as prominent African-Americans with Irish heritage. In the 1860s, Abe Grady left Ennis in County Clare to start a new life in America. He would make his home in Kentucky and marry a free African-American woman. The couple started a family, and one of their daughters was Odessa Lee Grady. Odessa met and married Cassius Clay, Sr. and on January 17, 1942, Cassius junior was born. Cassius Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali when he became a Muslim in 1964. Ali, an Olympic gold medalist at the 1960 games in Rome, has been suffering from Parkinson's for some years but was committed to raising funds for his center During his visit to Clare, he was mobbed by tens of thousands of locals who turned out to meet him and show him the area where his great-grandfather came from.Tracing Muhammad Ali's roots back to County Clare

Historian Dick Eastman had traced Ali’s roots back to Abe Grady the Clare emigrant to Kentucky and the freed slave he married. Eastman wrote: “An 1855 land survey of Ennis, a town in County Clare, Ireland, contains a reference to John Grady, who was renting a house in Turnpike Road in the center of the town. His rent payment was fifteen shillings a month. A few years later, his son Abe Grady immigrated to the United States. He settled in Kentucky." Also, around the year 1855, a man and a woman who were both freed slaves, originally from Liberia, purchased land in or around Duck Lick Creek, Logan, Kentucky. The two married, raised a family and farmed the land. These free blacks went by the name, Morehead, the name of white slave owners of the area. Odessa Grady Clay, Cassius Clay's mother, was the great-granddaughter of the freed slave Tom Morehead and of John Grady of Ennis, whose son Abe had emigrated from Ireland to the United States. She named her son Cassius in honor of a famous Kentucky abolitionist of that time. When he changed his name to Muhammad Ali in 1964, the famous boxer remarked, "Why should I keep my white slavemaster name visible and my black ancestors invisible, unknown, unhonored?" Ali was not only the greatest sporting figure, but he was also the best-known person in the world at his height, revered from Africa to Asia and all over the world. To the end, he was a battler, shown rare courage fighting Parkinson’s Disease, and surviving far longer than most sufferers from the disease. -

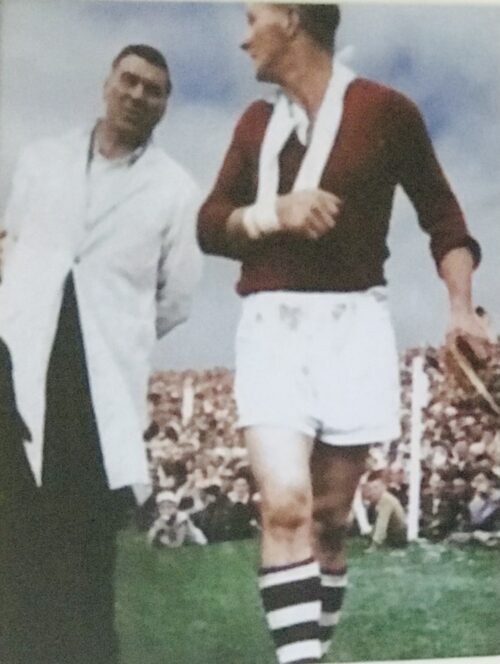

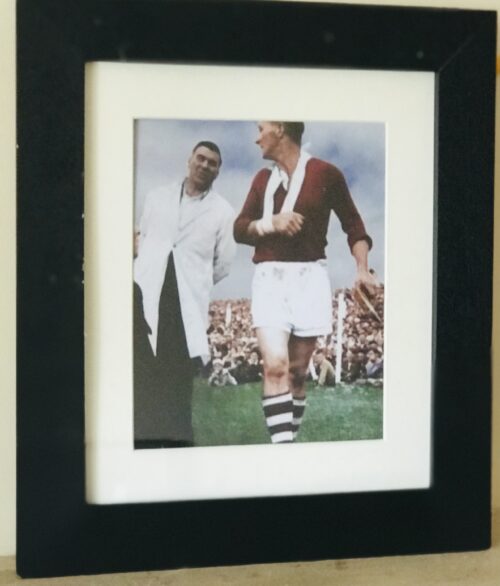

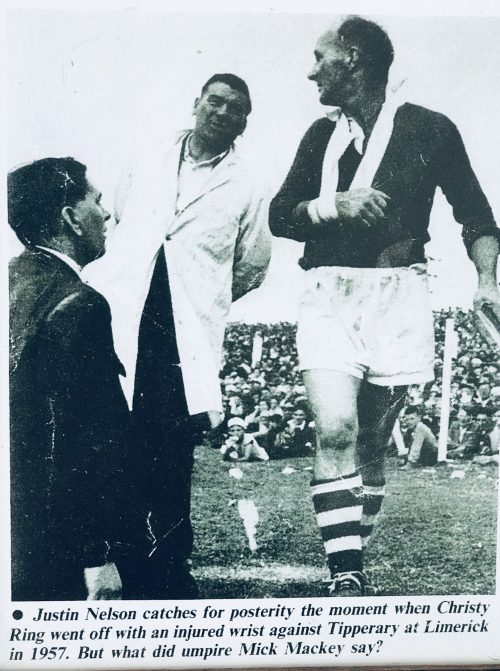

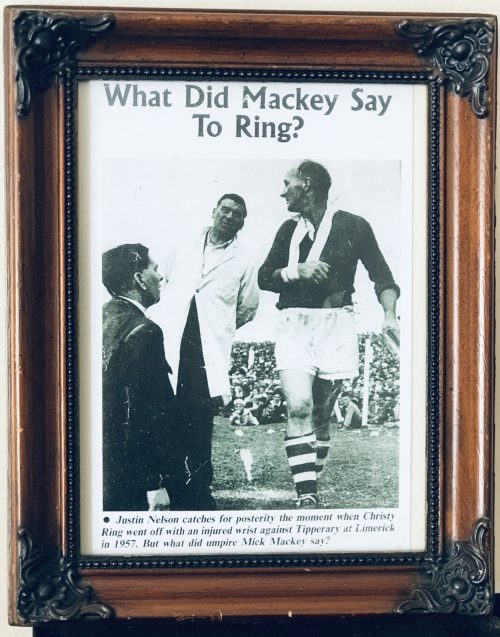

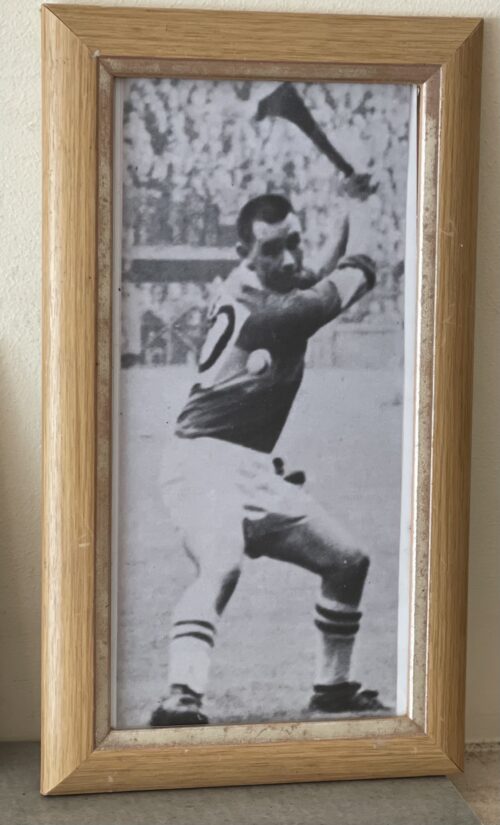

38cm x 33cm This time a colour version of the iconic photograph taken by Justin Nelson.The following explanation of the actual verbal exchange between the two legends comes from Michael Moynihan of the Examiner newspaper. "When Christy Ring left the field of play injured in the 1957 Munster championship game between Cork and Waterford at Limerick, he strolled behind the goal, where he passed Mick Mackey, who was acting as umpire for the game. The two exchanged a few words as Ring made his way to the dressing-room.It was an encounter that would have been long forgotten if not for the photograph snapped at precisely the moment the two men met. The picture freezes the moment forever: Mackey, though long retired, still vigorous, still dark haired, somehow incongruous in his umpire’s white coat, clearly hopping a ball; Ring at his fighting weight, his right wrist strapped, caught in the typical pose of a man fielding a remark coming over his shoulder and returning it with interest. Two hurling eras intersect in the two men’s encounter: Limerick’s glory of the 30s, and Ring’s dominance of two subsequent decades.But nobody recorded what was said, and the mystery has echoed down the decades.But Dan Barrett has the answer.He forged a friendship with Ring from the usual raw materials. They had girls the same age, they both worked for oil companies, they didn’t live that far away from each other. And they had hurling in common.We often chatted away at home about hurling,” says Barrett. “In general he wouldn’t criticise players, although he did say about one player for Cork, ‘if you put a whistle on the ball he might hear it’.” Barrett saw Ring’s awareness of his whereabouts at first hand; even in the heat of a game he was conscious of every factor in his surroundings. “We went up to see him one time in Thurles,” says Barrett. “Don’t forget, people would come from all over the country to see a game just for Ring, and the place was packed to the rafters – all along the sideline people were spilling in on the field. “He came out to take a sideline cut at one stage and we were all roaring at him – ‘Go on Ring’, the usual – and he looked up into the crowd, the blue eyes, and he looked right at me. “The following day in work he called in and we were having a chat, and I said ‘if you caught that sideline yesterday, you’d have driven it up to the Devil’s Bit.’ “There was another chap there who said about me, ‘With all his talk he probably wasn’t there at all’. ‘He was there alright,’ said Ring. ‘He was over in the corner of the stand’. He picked me out in the crowd.” “He told me there was no way he’d come on the team as a sub. I remember then when Cork beat Tipperary in the Munster championship for the first time in a long time, there was a helicopter landed near the ground, the Cork crowd were saying ‘here’s Ring’ to rise the Tipp crowd. “I saw his last goal, for the Glen against Blackrock. He collided with a Blackrock man and he took his shot, it wasn’t a hard one, but the keeper put his hurley down and it hopped over his stick.” There were tough days against Tipperary – Ring took off his shirt one Monday to show his friends the bruising across his back from one Tipp defender who had a special knack of letting the Corkman out ahead in order to punish him with his stick. But Ring added that when a disagreement at a Railway Cup game with Leinster became physical, all of Tipperary piled in to back him up. One evening the talk turned to the photograph. Barrett packed the audience – “I had my wife there as a witness,” – and asked Ring the burning question: what had Mackey said to him? “’You didn’t get half enough of it’, said Mackey. ‘I’d expect nothing different from you,’ said Ring. “That was what was said.” You might argue – with some credibility – that learning what was said by the two men removes some of the force of the photograph; that if you remained in ignorance you’d be free to project your own hypothetical dialogue on the freeze-frame meeting of the two men. But nothing trumps actuality. The exchange carries a double authenticity: the pungency of slagging from one corner and the weariness of riposte from the other. Dan Barrett just wanted to set the record straight. “I’d heard people say ‘it will never be known’ and so on,” he says.“I thought it was no harm to let people know.” No harm at all" Origins ; Co Limerick Dimensions : 31cm x 25cm 1kgBorn in Castleconnell, County Limerick,Mick Mackey first arrived on the inter-county scene at the age of seventeen when he first linked up with the Limerick minor team, before later lining out with the junior side. He made his senior debut in the 1930–31 National League. Mackey went on to play a key part for Limerick during a golden age for the team, and won three All-Ireland medals, five Munster medals and five National Hurling League medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on two occasions, Mackey also captained the team to two All-Ireland victories. His brother, John Mackey, also shared in these victories while his father, "Tyler" Mackey was a one-time All-Ireland runner-up with Limerick. Mackey represented the Munster inter-provincial team for twelve years, winning eight Railway Cup medals during that period. At club level he won fifteen championship medals with Ahane. Throughout his inter-county career, Mackey made 42 championship appearances for Limerick. His retirement came following the conclusion of the 1947 championship. In retirement from playing, Mackey became involved in team management and coaching. As trainer of the Limerick senior team in 1955, he guided them to Munster victory. He also served as a selector on various occasions with both Limerick and Munster. Mackey also served as a referee. Mackey is widely regarded as one of the greatest hurlers in the history of the game. He was the inaugural recipient of the All-Time All-Star Award. He has been repeatedly voted onto teams made up of the sport's greats, including at centre-forward on the Hurling Team of the Centuryin 1984 and the Hurling Team of the Millennium in 2000. Origins : Co Limerick Dimensions : 28cm x 37cm 1kg

38cm x 33cm This time a colour version of the iconic photograph taken by Justin Nelson.The following explanation of the actual verbal exchange between the two legends comes from Michael Moynihan of the Examiner newspaper. "When Christy Ring left the field of play injured in the 1957 Munster championship game between Cork and Waterford at Limerick, he strolled behind the goal, where he passed Mick Mackey, who was acting as umpire for the game. The two exchanged a few words as Ring made his way to the dressing-room.It was an encounter that would have been long forgotten if not for the photograph snapped at precisely the moment the two men met. The picture freezes the moment forever: Mackey, though long retired, still vigorous, still dark haired, somehow incongruous in his umpire’s white coat, clearly hopping a ball; Ring at his fighting weight, his right wrist strapped, caught in the typical pose of a man fielding a remark coming over his shoulder and returning it with interest. Two hurling eras intersect in the two men’s encounter: Limerick’s glory of the 30s, and Ring’s dominance of two subsequent decades.But nobody recorded what was said, and the mystery has echoed down the decades.But Dan Barrett has the answer.He forged a friendship with Ring from the usual raw materials. They had girls the same age, they both worked for oil companies, they didn’t live that far away from each other. And they had hurling in common.We often chatted away at home about hurling,” says Barrett. “In general he wouldn’t criticise players, although he did say about one player for Cork, ‘if you put a whistle on the ball he might hear it’.” Barrett saw Ring’s awareness of his whereabouts at first hand; even in the heat of a game he was conscious of every factor in his surroundings. “We went up to see him one time in Thurles,” says Barrett. “Don’t forget, people would come from all over the country to see a game just for Ring, and the place was packed to the rafters – all along the sideline people were spilling in on the field. “He came out to take a sideline cut at one stage and we were all roaring at him – ‘Go on Ring’, the usual – and he looked up into the crowd, the blue eyes, and he looked right at me. “The following day in work he called in and we were having a chat, and I said ‘if you caught that sideline yesterday, you’d have driven it up to the Devil’s Bit.’ “There was another chap there who said about me, ‘With all his talk he probably wasn’t there at all’. ‘He was there alright,’ said Ring. ‘He was over in the corner of the stand’. He picked me out in the crowd.” “He told me there was no way he’d come on the team as a sub. I remember then when Cork beat Tipperary in the Munster championship for the first time in a long time, there was a helicopter landed near the ground, the Cork crowd were saying ‘here’s Ring’ to rise the Tipp crowd. “I saw his last goal, for the Glen against Blackrock. He collided with a Blackrock man and he took his shot, it wasn’t a hard one, but the keeper put his hurley down and it hopped over his stick.” There were tough days against Tipperary – Ring took off his shirt one Monday to show his friends the bruising across his back from one Tipp defender who had a special knack of letting the Corkman out ahead in order to punish him with his stick. But Ring added that when a disagreement at a Railway Cup game with Leinster became physical, all of Tipperary piled in to back him up. One evening the talk turned to the photograph. Barrett packed the audience – “I had my wife there as a witness,” – and asked Ring the burning question: what had Mackey said to him? “’You didn’t get half enough of it’, said Mackey. ‘I’d expect nothing different from you,’ said Ring. “That was what was said.” You might argue – with some credibility – that learning what was said by the two men removes some of the force of the photograph; that if you remained in ignorance you’d be free to project your own hypothetical dialogue on the freeze-frame meeting of the two men. But nothing trumps actuality. The exchange carries a double authenticity: the pungency of slagging from one corner and the weariness of riposte from the other. Dan Barrett just wanted to set the record straight. “I’d heard people say ‘it will never be known’ and so on,” he says.“I thought it was no harm to let people know.” No harm at all" Origins ; Co Limerick Dimensions : 31cm x 25cm 1kgBorn in Castleconnell, County Limerick,Mick Mackey first arrived on the inter-county scene at the age of seventeen when he first linked up with the Limerick minor team, before later lining out with the junior side. He made his senior debut in the 1930–31 National League. Mackey went on to play a key part for Limerick during a golden age for the team, and won three All-Ireland medals, five Munster medals and five National Hurling League medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on two occasions, Mackey also captained the team to two All-Ireland victories. His brother, John Mackey, also shared in these victories while his father, "Tyler" Mackey was a one-time All-Ireland runner-up with Limerick. Mackey represented the Munster inter-provincial team for twelve years, winning eight Railway Cup medals during that period. At club level he won fifteen championship medals with Ahane. Throughout his inter-county career, Mackey made 42 championship appearances for Limerick. His retirement came following the conclusion of the 1947 championship. In retirement from playing, Mackey became involved in team management and coaching. As trainer of the Limerick senior team in 1955, he guided them to Munster victory. He also served as a selector on various occasions with both Limerick and Munster. Mackey also served as a referee. Mackey is widely regarded as one of the greatest hurlers in the history of the game. He was the inaugural recipient of the All-Time All-Star Award. He has been repeatedly voted onto teams made up of the sport's greats, including at centre-forward on the Hurling Team of the Centuryin 1984 and the Hurling Team of the Millennium in 2000. Origins : Co Limerick Dimensions : 28cm x 37cm 1kg -

25cm x 20cm Abbeyfeale Co Limerick Nice souvenir of the iconic photograph taken by Justin Nelson.The following explanation of the actual verbal exchange between the two legends comes from Michael Moynihan of the Examiner newspaper. "When Christy Ring left the field of play injured in the 1957 Munster championship game between Cork and Waterford at Limerick, he strolled behind the goal, where he passed Mick Mackey, who was acting as umpire for the game. The two exchanged a few words as Ring made his way to the dressing-room.It was an encounter that would have been long forgotten if not for the photograph snapped at precisely the moment the two men met. The picture freezes the moment forever: Mackey, though long retired, still vigorous, still dark haired, somehow incongruous in his umpire’s white coat, clearly hopping a ball; Ring at his fighting weight, his right wrist strapped, caught in the typical pose of a man fielding a remark coming over his shoulder and returning it with interest. Two hurling eras intersect in the two men’s encounter: Limerick’s glory of the 30s, and Ring’s dominance of two subsequent decades.But nobody recorded what was said, and the mystery has echoed down the decades.But Dan Barrett has the answer.He forged a friendship with Ring from the usual raw materials. They had girls the same age, they both worked for oil companies, they didn’t live that far away from each other. And they had hurling in common.We often chatted away at home about hurling,” says Barrett. “In general he wouldn’t criticise players, although he did say about one player for Cork, ‘if you put a whistle on the ball he might hear it’.” Barrett saw Ring’s awareness of his whereabouts at first hand; even in the heat of a game he was conscious of every factor in his surroundings. “We went up to see him one time in Thurles,” says Barrett. “Don’t forget, people would come from all over the country to see a game just for Ring, and the place was packed to the rafters – all along the sideline people were spilling in on the field. “He came out to take a sideline cut at one stage and we were all roaring at him – ‘Go on Ring’, the usual – and he looked up into the crowd, the blue eyes, and he looked right at me. “The following day in work he called in and we were having a chat, and I said ‘if you caught that sideline yesterday, you’d have driven it up to the Devil’s Bit.’ “There was another chap there who said about me, ‘With all his talk he probably wasn’t there at all’. ‘He was there alright,’ said Ring. ‘He was over in the corner of the stand’. He picked me out in the crowd.” “He told me there was no way he’d come on the team as a sub. I remember then when Cork beat Tipperary in the Munster championship for the first time in a long time, there was a helicopter landed near the ground, the Cork crowd were saying ‘here’s Ring’ to rise the Tipp crowd. “I saw his last goal, for the Glen against Blackrock. He collided with a Blackrock man and he took his shot, it wasn’t a hard one, but the keeper put his hurley down and it hopped over his stick.” There were tough days against Tipperary – Ring took off his shirt one Monday to show his friends the bruising across his back from one Tipp defender who had a special knack of letting the Corkman out ahead in order to punish him with his stick. But Ring added that when a disagreement at a Railway Cup game with Leinster became physical, all of Tipperary piled in to back him up. One evening the talk turned to the photograph. Barrett packed the audience – “I had my wife there as a witness,” – and asked Ring the burning question: what had Mackey said to him? “’You didn’t get half enough of it’, said Mackey. ‘I’d expect nothing different from you,’ said Ring. “That was what was said.” You might argue – with some credibility – that learning what was said by the two men removes some of the force of the photograph; that if you remained in ignorance you’d be free to project your own hypothetical dialogue on the freeze-frame meeting of the two men. But nothing trumps actuality. The exchange carries a double authenticity: the pungency of slagging from one corner and the weariness of riposte from the other. Dan Barrett just wanted to set the record straight. “I’d heard people say ‘it will never be known’ and so on,” he says.“I thought it was no harm to let people know.” No harm at all" Origins ; Co Limerick Dimensions : 31cm x 25cm 1kgBorn in Castleconnell, County Limerick,Mick Mackey first arrived on the inter-county scene at the age of seventeen when he first linked up with the Limerick minor team, before later lining out with the junior side. He made his senior debut in the 1930–31 National League. Mackey went on to play a key part for Limerick during a golden age for the team, and won three All-Ireland medals, five Munster medals and five National Hurling League medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on two occasions, Mackey also captained the team to two All-Ireland victories. His brother, John Mackey, also shared in these victories while his father, "Tyler" Mackey was a one-time All-Ireland runner-up with Limerick. Mackey represented the Munster inter-provincial team for twelve years, winning eight Railway Cup medals during that period. At club level he won fifteen championship medals with Ahane. Throughout his inter-county career, Mackey made 42 championship appearances for Limerick. His retirement came following the conclusion of the 1947 championship. In retirement from playing, Mackey became involved in team management and coaching. As trainer of the Limerick senior team in 1955, he guided them to Munster victory. He also served as a selector on various occasions with both Limerick and Munster. Mackey also served as a referee. Mackey is widely regarded as one of the greatest hurlers in the history of the game. He was the inaugural recipient of the All-Time All-Star Award. He has been repeatedly voted onto teams made up of the sport's greats, including at centre-forward on the Hurling Team of the Centuryin 1984 and the Hurling Team of the Millennium in 2000. Origins : Co Limerick Dimensions : 28cm x 37cm 1kg

25cm x 20cm Abbeyfeale Co Limerick Nice souvenir of the iconic photograph taken by Justin Nelson.The following explanation of the actual verbal exchange between the two legends comes from Michael Moynihan of the Examiner newspaper. "When Christy Ring left the field of play injured in the 1957 Munster championship game between Cork and Waterford at Limerick, he strolled behind the goal, where he passed Mick Mackey, who was acting as umpire for the game. The two exchanged a few words as Ring made his way to the dressing-room.It was an encounter that would have been long forgotten if not for the photograph snapped at precisely the moment the two men met. The picture freezes the moment forever: Mackey, though long retired, still vigorous, still dark haired, somehow incongruous in his umpire’s white coat, clearly hopping a ball; Ring at his fighting weight, his right wrist strapped, caught in the typical pose of a man fielding a remark coming over his shoulder and returning it with interest. Two hurling eras intersect in the two men’s encounter: Limerick’s glory of the 30s, and Ring’s dominance of two subsequent decades.But nobody recorded what was said, and the mystery has echoed down the decades.But Dan Barrett has the answer.He forged a friendship with Ring from the usual raw materials. They had girls the same age, they both worked for oil companies, they didn’t live that far away from each other. And they had hurling in common.We often chatted away at home about hurling,” says Barrett. “In general he wouldn’t criticise players, although he did say about one player for Cork, ‘if you put a whistle on the ball he might hear it’.” Barrett saw Ring’s awareness of his whereabouts at first hand; even in the heat of a game he was conscious of every factor in his surroundings. “We went up to see him one time in Thurles,” says Barrett. “Don’t forget, people would come from all over the country to see a game just for Ring, and the place was packed to the rafters – all along the sideline people were spilling in on the field. “He came out to take a sideline cut at one stage and we were all roaring at him – ‘Go on Ring’, the usual – and he looked up into the crowd, the blue eyes, and he looked right at me. “The following day in work he called in and we were having a chat, and I said ‘if you caught that sideline yesterday, you’d have driven it up to the Devil’s Bit.’ “There was another chap there who said about me, ‘With all his talk he probably wasn’t there at all’. ‘He was there alright,’ said Ring. ‘He was over in the corner of the stand’. He picked me out in the crowd.” “He told me there was no way he’d come on the team as a sub. I remember then when Cork beat Tipperary in the Munster championship for the first time in a long time, there was a helicopter landed near the ground, the Cork crowd were saying ‘here’s Ring’ to rise the Tipp crowd. “I saw his last goal, for the Glen against Blackrock. He collided with a Blackrock man and he took his shot, it wasn’t a hard one, but the keeper put his hurley down and it hopped over his stick.” There were tough days against Tipperary – Ring took off his shirt one Monday to show his friends the bruising across his back from one Tipp defender who had a special knack of letting the Corkman out ahead in order to punish him with his stick. But Ring added that when a disagreement at a Railway Cup game with Leinster became physical, all of Tipperary piled in to back him up. One evening the talk turned to the photograph. Barrett packed the audience – “I had my wife there as a witness,” – and asked Ring the burning question: what had Mackey said to him? “’You didn’t get half enough of it’, said Mackey. ‘I’d expect nothing different from you,’ said Ring. “That was what was said.” You might argue – with some credibility – that learning what was said by the two men removes some of the force of the photograph; that if you remained in ignorance you’d be free to project your own hypothetical dialogue on the freeze-frame meeting of the two men. But nothing trumps actuality. The exchange carries a double authenticity: the pungency of slagging from one corner and the weariness of riposte from the other. Dan Barrett just wanted to set the record straight. “I’d heard people say ‘it will never be known’ and so on,” he says.“I thought it was no harm to let people know.” No harm at all" Origins ; Co Limerick Dimensions : 31cm x 25cm 1kgBorn in Castleconnell, County Limerick,Mick Mackey first arrived on the inter-county scene at the age of seventeen when he first linked up with the Limerick minor team, before later lining out with the junior side. He made his senior debut in the 1930–31 National League. Mackey went on to play a key part for Limerick during a golden age for the team, and won three All-Ireland medals, five Munster medals and five National Hurling League medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on two occasions, Mackey also captained the team to two All-Ireland victories. His brother, John Mackey, also shared in these victories while his father, "Tyler" Mackey was a one-time All-Ireland runner-up with Limerick. Mackey represented the Munster inter-provincial team for twelve years, winning eight Railway Cup medals during that period. At club level he won fifteen championship medals with Ahane. Throughout his inter-county career, Mackey made 42 championship appearances for Limerick. His retirement came following the conclusion of the 1947 championship. In retirement from playing, Mackey became involved in team management and coaching. As trainer of the Limerick senior team in 1955, he guided them to Munster victory. He also served as a selector on various occasions with both Limerick and Munster. Mackey also served as a referee. Mackey is widely regarded as one of the greatest hurlers in the history of the game. He was the inaugural recipient of the All-Time All-Star Award. He has been repeatedly voted onto teams made up of the sport's greats, including at centre-forward on the Hurling Team of the Centuryin 1984 and the Hurling Team of the Millennium in 2000. Origins : Co Limerick Dimensions : 28cm x 37cm 1kg -

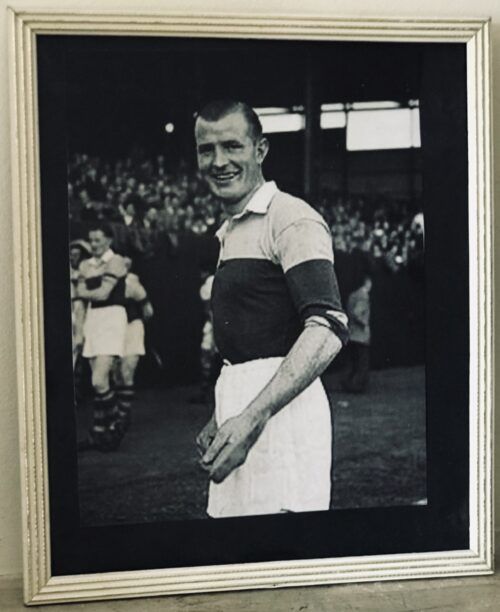

Poignant portrait of all time Wexford Hurling Great Nicky Rackard Enniscorthy Co Wexford 35cm x32cm "I was lucky enough to be on a Wexford team that he was involved with," recalled Liam Griffin. "He put his hand on my shoulder and that was like the hand of God touching you. "He was a fantastic man and his presence was just unbelievable. To see him standing there in a dressing-room, you wouldn't be worried about going out on the pitch, you'd just be looking at him." Despite his many years of service to Wexford GAA, Nicky Rackard's life was cut tragically short and at only the age of 53, the legendary hurler passed on after a battle with cancer. As Liam Griffin recalled on OTB AM, Rackard had also had his struggles with alcohol. "He was a gentleman as well, but look, he had his problems when he wasn't a gentleman as well when he had drink taken like most people," he explained. "But look, he was an inspiration too because he went on to do great work for alcoholics and so forth. "But I'm just going to say this, and I'm not saying this to be smart but because I mean it sincerely. After the All-Ireland final when we won it we put the cup in the middle of the floor the next morning after the All-Ireland. "In my view, he'd had such an influence on me and what we were that we stood around the cup and said a few prayers, and I'm not ashamed to say that I can tell you. "I warned them, and I meant it because I had thought about it in the previous weeks and months before, about any of them becoming an alcoholic, like Nicky Rackard. "He was one of the greatest but hero-worship is dangerous and when they walked out that door their lives would change forever. Nicky's life was spoiled by the worship he received and that's an unintended consequence, but it is the truth." The prominent figure upon Wexford's Mt Rushmore in Liam Griffin's opinion, whatever of Nicky Rackard's troubles in life, Griffin believes his legacy as a hurler is unsurpassed. "He led Wexford when we hadn't fields of barley let me tell you, we had pretty barren fields," he recalled. "Nicky Rackard carried on through a lot of thick and thin with Wexford, through a lot of heartache but he eventually put his flag on the top of the mountain. "He's #1 in Wexford, that's for sure."

Poignant portrait of all time Wexford Hurling Great Nicky Rackard Enniscorthy Co Wexford 35cm x32cm "I was lucky enough to be on a Wexford team that he was involved with," recalled Liam Griffin. "He put his hand on my shoulder and that was like the hand of God touching you. "He was a fantastic man and his presence was just unbelievable. To see him standing there in a dressing-room, you wouldn't be worried about going out on the pitch, you'd just be looking at him." Despite his many years of service to Wexford GAA, Nicky Rackard's life was cut tragically short and at only the age of 53, the legendary hurler passed on after a battle with cancer. As Liam Griffin recalled on OTB AM, Rackard had also had his struggles with alcohol. "He was a gentleman as well, but look, he had his problems when he wasn't a gentleman as well when he had drink taken like most people," he explained. "But look, he was an inspiration too because he went on to do great work for alcoholics and so forth. "But I'm just going to say this, and I'm not saying this to be smart but because I mean it sincerely. After the All-Ireland final when we won it we put the cup in the middle of the floor the next morning after the All-Ireland. "In my view, he'd had such an influence on me and what we were that we stood around the cup and said a few prayers, and I'm not ashamed to say that I can tell you. "I warned them, and I meant it because I had thought about it in the previous weeks and months before, about any of them becoming an alcoholic, like Nicky Rackard. "He was one of the greatest but hero-worship is dangerous and when they walked out that door their lives would change forever. Nicky's life was spoiled by the worship he received and that's an unintended consequence, but it is the truth." The prominent figure upon Wexford's Mt Rushmore in Liam Griffin's opinion, whatever of Nicky Rackard's troubles in life, Griffin believes his legacy as a hurler is unsurpassed. "He led Wexford when we hadn't fields of barley let me tell you, we had pretty barren fields," he recalled. "Nicky Rackard carried on through a lot of thick and thin with Wexford, through a lot of heartache but he eventually put his flag on the top of the mountain. "He's #1 in Wexford, that's for sure." -

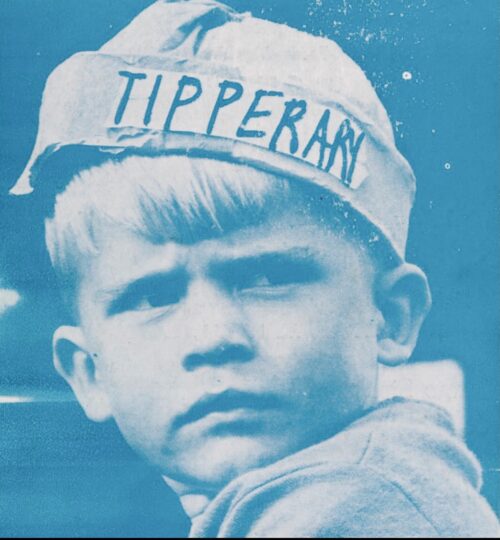

Fantastic piece of Tipperary Hurling Nostalgia here as we see a very young Jimmy Doyle being presented with a Thurles Schoolboys Streel League Trophy. 45cm x 35cm. Thurles Co Tipperary "Jimmy Doyle would have seen many things, and watched a lot of hurling, in his 76 years. But the Tipperary legend, who died last Monday, was possibly most pleased to watch the sumptuous performance of his native county, against Limerick, just the day before. Simply put, the way Tipp hurl at the moment is pure Jimmy Doyle - and no finer compliment can be paid in the Premier County. Eamon O'Shea's current group are all about skill, vision, élan, creativity, elegance: the very things which defined Doyle's playing style as he terrorised defences for close on two decades. Indeed, it's a funny irony that the Thurles Sarsfields icon, were he young today, would easily slip into the modern game, such was his impeccable technique, flair and positional sense. There may have been "better" hurlers in history (Cork's Christy Ring surely still stands as the greatest of all). There may even have been better Tipp hurlers - John Doyle, for example, who won more All-Irelands than his namesake. But there was hardly a more naturally gifted man to play in 125 years. The hurling of Doyle's heyday, by contrast with today, was rough, tough, sometimes brutal. His own Tipp team featured a full-back line so feared for taking no prisoners, they were christened (not entirely unaffectionately) "Hell's Kitchen". While not quite unique, Doyle was one of a select group back then who relied less on brute force, and more on quick wrists, "sixth sense" spatial awareness, and uncanny eye-hand co-ordination to overcome. During the 1950s and '60s, when he was in his pomp, forwards were battered, bruised and banjaxed, with little protection from rules or referees. It speaks even more highly, then, of this small, slim man ("no bigger in stature than a jockey", as put by Irish Independent sportswriter Vincent Hogan) that he should achieve such greatness. What, you'd wonder, might have been his limitations - if any - had he played in the modern game? Regardless, his place in hurling's pantheon is assured; one of a handful of players to transcend even greatness and enter some almost supernatural realm of brilliance. This week his former teammate, and fellow Tipp legend, Michael "Babs" Keating recalled how Christy Ring had once told him, "If Jimmy Doyle was as strong as you and I, nobody would ever ask who was the best." Like Ring, Jimmy made both the 1984 hurling Team of the Century, compiled in honour of the GAA's Centenary, and the later Team of the Millennium. We can also throw in a slot on both Tipperary and Munster Teams of the Millennium, and being named Hurler of the Year in 1965 - and that's just the start of one of the most glittering collections of honours in hurling history.

Fantastic piece of Tipperary Hurling Nostalgia here as we see a very young Jimmy Doyle being presented with a Thurles Schoolboys Streel League Trophy. 45cm x 35cm. Thurles Co Tipperary "Jimmy Doyle would have seen many things, and watched a lot of hurling, in his 76 years. But the Tipperary legend, who died last Monday, was possibly most pleased to watch the sumptuous performance of his native county, against Limerick, just the day before. Simply put, the way Tipp hurl at the moment is pure Jimmy Doyle - and no finer compliment can be paid in the Premier County. Eamon O'Shea's current group are all about skill, vision, élan, creativity, elegance: the very things which defined Doyle's playing style as he terrorised defences for close on two decades. Indeed, it's a funny irony that the Thurles Sarsfields icon, were he young today, would easily slip into the modern game, such was his impeccable technique, flair and positional sense. There may have been "better" hurlers in history (Cork's Christy Ring surely still stands as the greatest of all). There may even have been better Tipp hurlers - John Doyle, for example, who won more All-Irelands than his namesake. But there was hardly a more naturally gifted man to play in 125 years. The hurling of Doyle's heyday, by contrast with today, was rough, tough, sometimes brutal. His own Tipp team featured a full-back line so feared for taking no prisoners, they were christened (not entirely unaffectionately) "Hell's Kitchen". While not quite unique, Doyle was one of a select group back then who relied less on brute force, and more on quick wrists, "sixth sense" spatial awareness, and uncanny eye-hand co-ordination to overcome. During the 1950s and '60s, when he was in his pomp, forwards were battered, bruised and banjaxed, with little protection from rules or referees. It speaks even more highly, then, of this small, slim man ("no bigger in stature than a jockey", as put by Irish Independent sportswriter Vincent Hogan) that he should achieve such greatness. What, you'd wonder, might have been his limitations - if any - had he played in the modern game? Regardless, his place in hurling's pantheon is assured; one of a handful of players to transcend even greatness and enter some almost supernatural realm of brilliance. This week his former teammate, and fellow Tipp legend, Michael "Babs" Keating recalled how Christy Ring had once told him, "If Jimmy Doyle was as strong as you and I, nobody would ever ask who was the best." Like Ring, Jimmy made both the 1984 hurling Team of the Century, compiled in honour of the GAA's Centenary, and the later Team of the Millennium. We can also throw in a slot on both Tipperary and Munster Teams of the Millennium, and being named Hurler of the Year in 1965 - and that's just the start of one of the most glittering collections of honours in hurling history. -

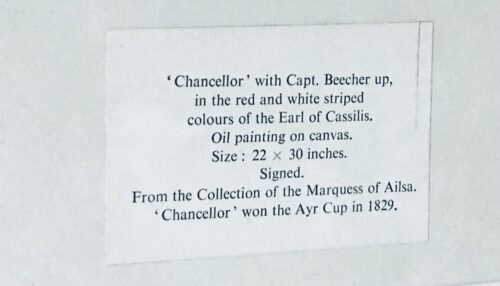

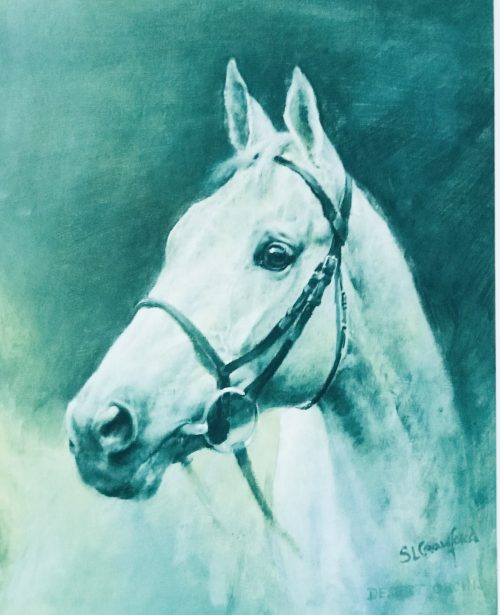

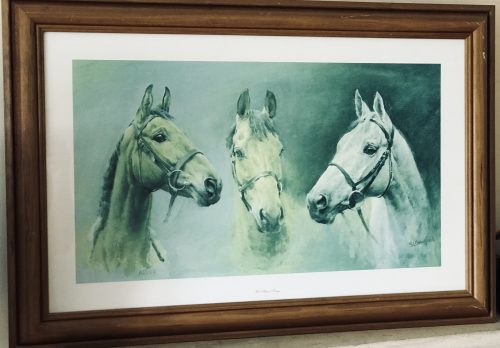

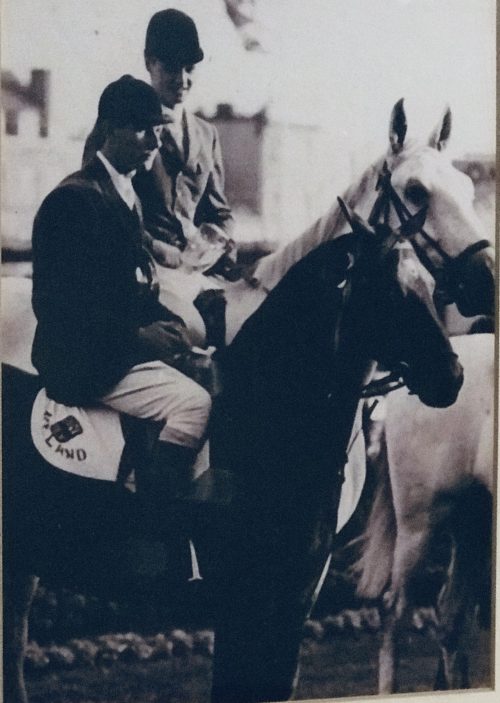

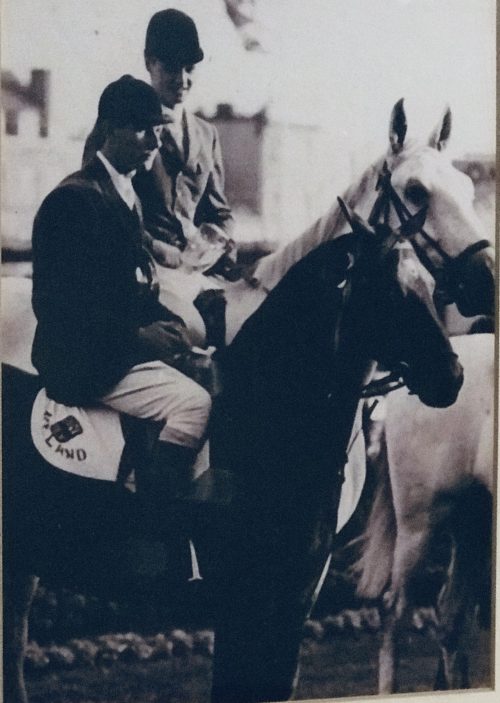

47cm x 35cm During its 180 year history, the Grand National has seen only five horses win consecutive runnings, with this year's victor Tiger Roll joining that exclusive list of dual winners. Until the legendary Red Rum, the last horse to win on his immediate return to Aintree was Reynoldstown, who won the 1935 Grand National in the hands of Mr Frank Furlong - a subaltern in the 9th Lancers - and again the following year ridden by Furlong's great friend and fellow Army officer Mr Fulke Walwyn, later to become a multi-time champion National Hunt trainer. Although two totally different kinds of horses, the long, lean, black Reynoldstown and the diminutive Tiger Roll share a parallel in that both had Flat-bred sires. Reynoldstown was by the good-class My Prince who won among other races the Union Jack Stakes at Aintree but went on to become more famous as an outstanding sire of National Hunt horses including Grand National winners Gregalach (1929) and Royal Mail (1937), while Tiger Roll's father Authorized won the 2007 Epsom Derby under Frankie Dettori. Reynoldstown's dam Fromage was the product of a modest mating to the nearest sire who was within walking distance.

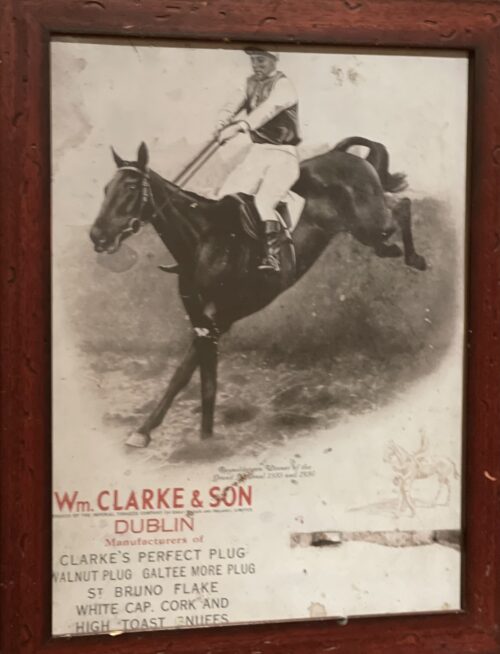

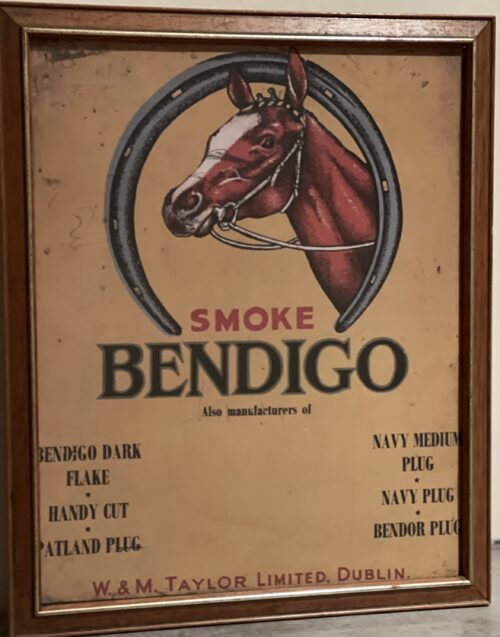

47cm x 35cm During its 180 year history, the Grand National has seen only five horses win consecutive runnings, with this year's victor Tiger Roll joining that exclusive list of dual winners. Until the legendary Red Rum, the last horse to win on his immediate return to Aintree was Reynoldstown, who won the 1935 Grand National in the hands of Mr Frank Furlong - a subaltern in the 9th Lancers - and again the following year ridden by Furlong's great friend and fellow Army officer Mr Fulke Walwyn, later to become a multi-time champion National Hunt trainer. Although two totally different kinds of horses, the long, lean, black Reynoldstown and the diminutive Tiger Roll share a parallel in that both had Flat-bred sires. Reynoldstown was by the good-class My Prince who won among other races the Union Jack Stakes at Aintree but went on to become more famous as an outstanding sire of National Hunt horses including Grand National winners Gregalach (1929) and Royal Mail (1937), while Tiger Roll's father Authorized won the 2007 Epsom Derby under Frankie Dettori. Reynoldstown's dam Fromage was the product of a modest mating to the nearest sire who was within walking distance.Reynoldstown, named after the local townland of the small village of Naul near Dublin, was foaled there in 1927 by cattle farmer Dick Ball - who also bred the great Ballymoss. Dick's father had raised Fromage by hand himself after her mother died foaling. As a five-year-old, Reynoldstown was bought for £1,500 by Major Noel Furlong for his son Frank to ride in steeplechases. A leading Irish point-to-point rider himself, Major Furlong had had his interest in the Grand National sparked one year when, still in the Army, he'd travelled to Liverpool to watch the big race. In the train carriage, he overheard people talking about the chances of their horse winning and, when he saw this come to pass later that day, declared "That's it! I'm going to win the National myself." Major Furlong trained just two or three horses of his own in Skeffington, Leicestershire. Reynoldstown proved to be very hot and excitable throughout his career and was never ridden by anyone - at home or in races - apart from Major Furlong, Frank or Fulke. Reynoldstown won four hurdle races and eight 'chases before his first Grand National success in 1935, which saw him score by three lengths and break Golden Miller's record for the race - his time of 9 minutes 20.20 seconds standing until Red Rum beat it in 1973. The newspaper headlines ran: "Grand National won by two Furlongs!" Reynoldstown suffered leg problems afterwards which forced a long lay-off. Major Furlong followed the old adage "time, tar and tarmac", coating his legs with tar and giving him lots of roadwork to get him sound again. The horse duly came back to win the 1936 Grand National by twelve lengths, this time in the hands of Walwyn, since Frank Furlong was unable to make the weight. There was drama at the final fence after the reins broke on challenger Davy Jones, leaving rider Anthony Mildmay (after whom the Mildmay Course at Aintree is named) powerless to prevent the horse running out into the crowds. Reynoldstown did not attempt the hat trick. He was retired immediately after his Grand National success, the Furlongs considering - not unlike the connections of Tiger Roll - that he had done enough to prove himself and owing them nothing. He spent his retirement with Major Furlong at Marston St Lawrence near Banbury, where he was put down at the age of 24 after contracting tetanus. He is buried there, alongside the 1972 Grand National winner Well To Do. Curiously, he was never turned out in the field but was exercised instead on a lungeing rein by his devoted lifelong groom McCarthy, who brushed him and took him for a pick of grass and a welcome roll every day. Sadly, for Major Furlong, the aftermath was not so happy. His son Frank, who had left the Army and set up training himself near Lambourn, enlisted in the Fleet Air Arm at the outbreak of World War II and, though flying successfully on many combat missions, was killed when the Spitfire prototype Spiteful he was testing developed a fault and crashed on Salisbury Plain in 1944. He left a widow and a baby daughter, Grizelda, who today, as an octogenarian, recalls with affection being brought up by her grandparents and sitting on Reynoldstown's back as a pony-mad youngster. She clearly remembers stories Major Furlong would tell, including that of the 1934 Grand National in which both Frank and Fulke rode. Both their horses came down at the 26th fence when going well and the two riders were left thumping the turf in frustration. Major Furlong confronted the disgruntled friends in the Weighing Room afterwards with the prophetic words: "Don't worry, I shall have a Grand National winner for both of you." Another tale he told her concerned Frank and Fulke, in a hurry to reach the traditional party at the Adelphi Hotel, joyfully overtaking the traffic jams outside Aintree after one of their National wins. A policeman pulled the singing and shouting pair over with the words "What do you think you're doing? Anyone would think you'd just won the Grand National!" Grizelda smiles when she recounts her grandfather telling her how Reynoldstown's horsebox was held up by a funeral on the way to the 1935 Grand National. Major Furlong considered it lucky to see a funeral so the following year waited around in the hope of another before they reached the course. None appeared - but they did manage to spot a black cat - which obviously had the same desired effect. Quote: Attempting to compare Reynoldstown and Tiger Roll, Grizelda says: "The Grand National today is a totally different race and the fences are so much smaller. You cannot compare the two, but Tiger Roll is obviously a wonderful horse and thoroughly deserved both his wins and the adulation he received. We always gathered round as a family to watch the National on TV and this year was no exception. I really did think Tiger Roll would win." William Clarke & Son was a tobacco company that was founded in 1830 at South Main Street, Cork, Ireland. In January 1924, following the formation of the Irish Free State, the United Kingdom trade of William Clarke & Son was transferred to Dublin and taken over by Ogden's.

William Clarke & Son, Dublin

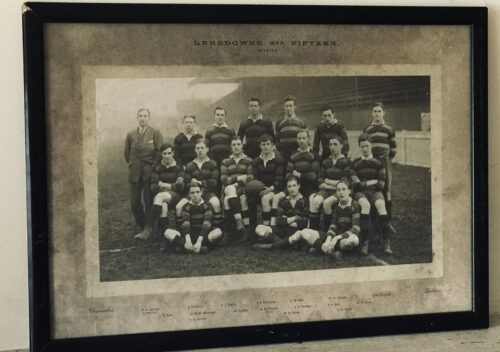

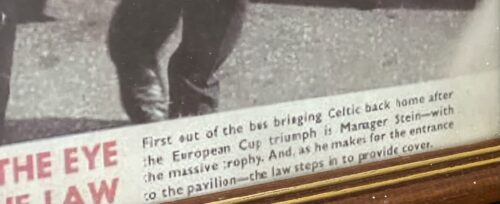

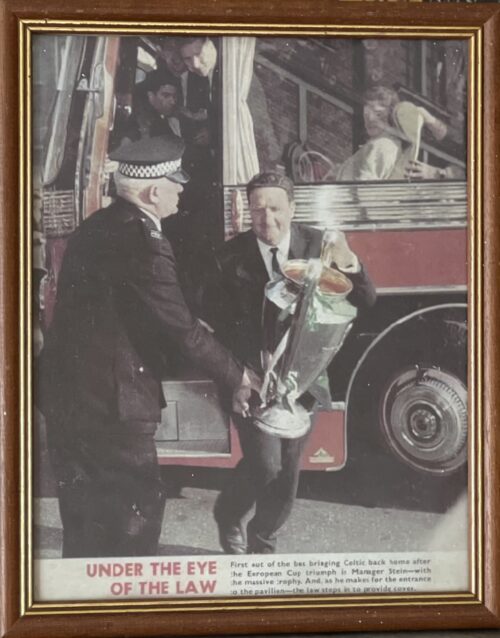

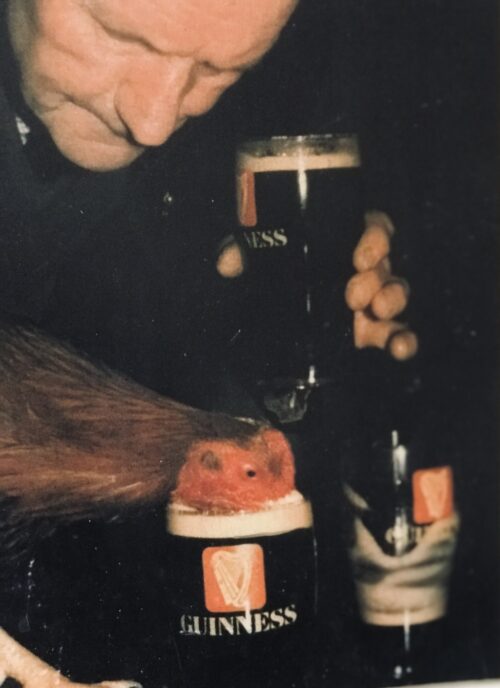

William Clarke was founded in 1830 at South Main Street in Cork, however by 1870 the manufacturing side of the business had all been transferred to Hare Place, Scotland Road, Liverpool, with only depots remaining in Ireland. Following the formation of the Irish Free State in 1926, the Liverpool based operation was taken over by Ogden’s, while a new factory was set up at South Circular Road in Dublin to produce tobacco and snuff under the William Clarke & Son brand. In 1929 William Clarke was amalgamated with Wills’s Irish branch, which resulted in Wills’s Irish production being integrated into the new South Circular Road factory in Dublin, though senior management were based in Wills’s Bristol operations and the Irish entity ultimately reported back into Bristol. -