-

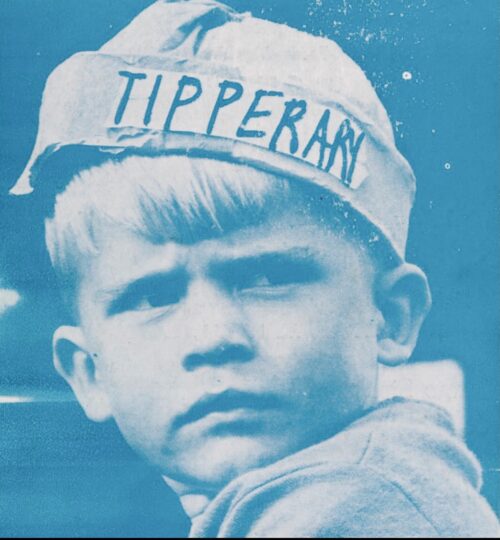

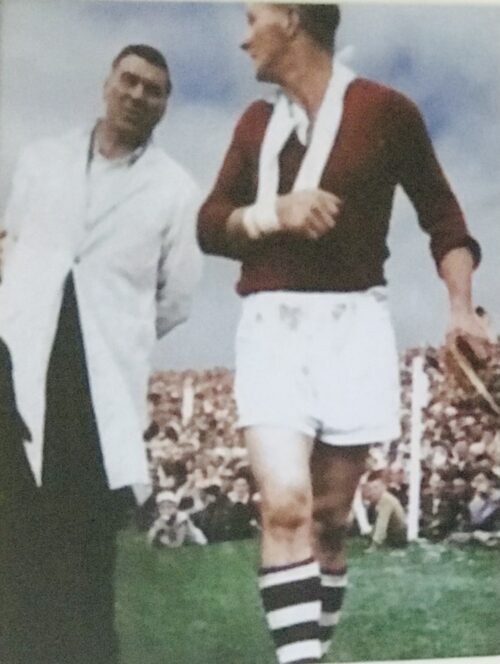

48cm x 39cm. Dublin July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history.

48cm x 39cm. Dublin July 19, 1972, Muhammad Ali fought Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park in Dublin, causing quite a stir in Ireland.Decades later, an Irish documentary recounting the epic fight not only won awards but also won the approval of Ali's daughter Jamilah Ali. "When Ali Came to Ireland" is an Irish documentary that details Muhammad Ali's trip to Dublin for a fight against Al 'Blue' Lewis at Croke Park. In 2013 the film was screened at the Chicago film festival, where Jamilah Ali was in attendance. TheJournal.ie reported that following the screening, Jamilah said "I've seen so much footage of my father over the years but the amazing thing about watching this film was that I had seen none of the footage of him in Ireland... I loved the film from the beginning to the end." The film highlights a moment in Ali's career where he was set to stage a world comeback. He had been recently released from prison after refusing to join the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector. His opponent Al Lewis had also just been released on parole after serving time in Detroit for a murder charge, and he intended to use his boxing career as "a path to a new life." The movie that won an IFTA in 2013 documents the spectacle in Croke Park, Ali's presence in Ireland and how the public reacted to his being there. It also demonstrates how Ali came to be in Dublin for a fight in the first place, highlighting the involvement of "former Kerry strongman"Michael "Butty" Sugrue. Sugrue's story also proved to be revelatory to his family- in a quote from Ross Whittaker, co-director of the film, he speaks about how Sugrue's grandchildren had never had the chance to meet him. "We were amazed when we screened the film in London to find that Butty Sugrue's granddaughters had never heard their grandfather speak. He had died before they were born and they'd never seen footage of him in which he had spoken." After their 1972 meeting, however, Sugrue and Ali's fortunes took two divergent paths. Ali returned to the ring in America to further glories and fanfare before his retirement, while Sugrue lost a small fortune on the Dublin fight and after dying in London was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in his hometown of Killorglin, Co Kerry. The Louisville Lip was also incredibly proud of his County Clare roots. Today we recall the man's star quality and his Irish ancestry. The death of boxing legend Muhammad Ali at 74 in June 2016, from Parkinson’s, would have brought back many glorious memories of the greatest athlete of our times. At the height of his career, Ali was the most graceful, talented, and brilliant heavyweight boxer who ever stepped inside the ropes. I remember seeing him enter the room at the American Ireland Fund dinner in 2011 and grown men, including the Irish leader Enda Kenny, were simply awestruck that they were in the presence of the greatest living legend. Ali was more than a boxer, of course, he was a fighter who refused to become cannon fodder in the Vietnam War, the greatest mistaken war America entered until the invasion of Iraq. He was also a poet, a showman, a lover of many women, a devout Muslim, and simply a legend. Ali's stance to end the Vietnam War when he refused to be drafted cost us the best years of his sporting life. He came back still a brilliant boxer, but the man who could float like a butterfly could never quite recover that greatness. Still, the fights with Joe Frazier, the rope-a-dope that saw him defeat George Foreman in Zaire in the "Rumble in the Jungle" will forever enshrine his name in history. -

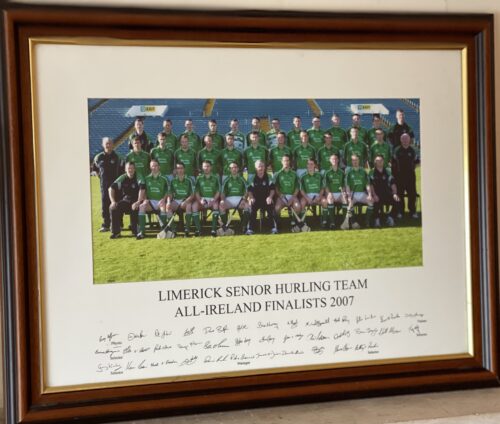

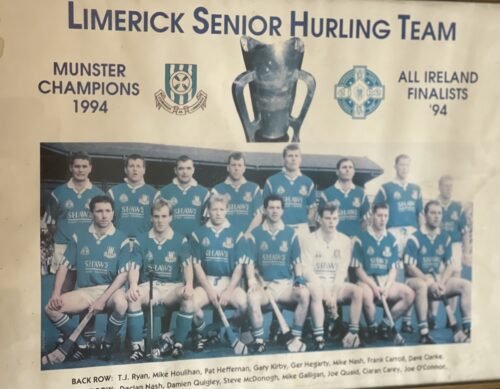

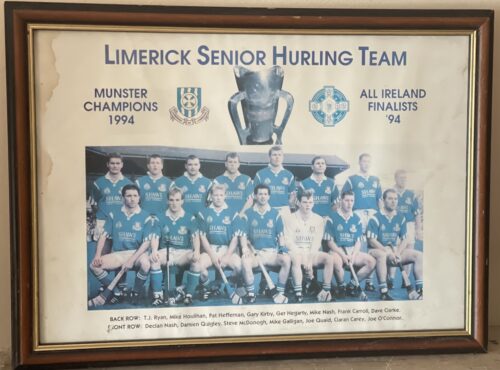

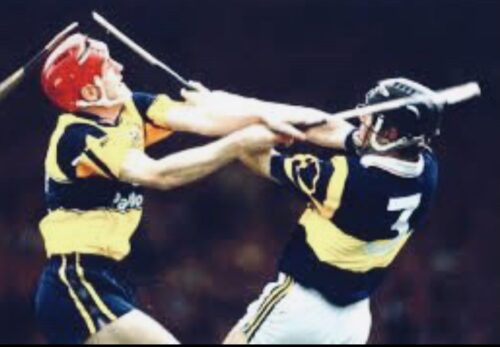

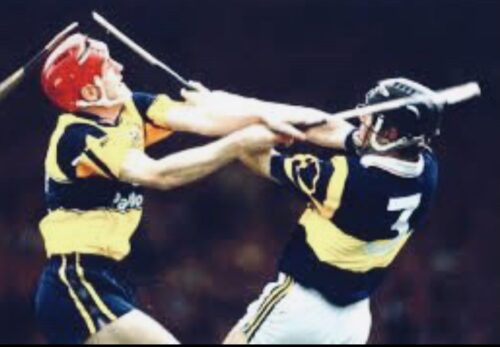

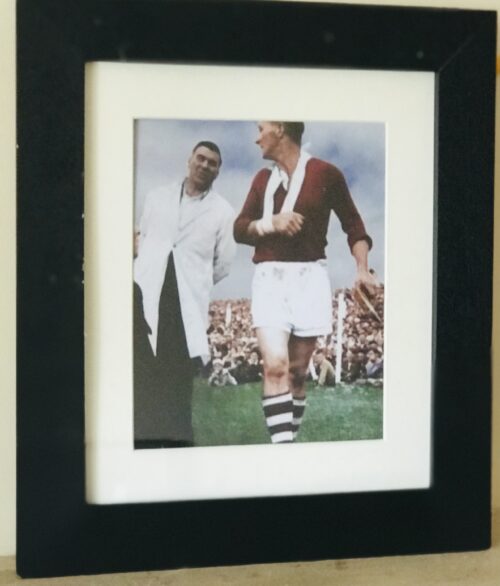

Framed photo of the gallant 2007 Limerick Hurlers who reached the All Ireland final where they were beaten by an all time great Kilkenny Team. 53cm x 68cm Limerick In 2007, Limerick shook up the hurling landscape by reaching their first All Ireland final since 1996 in an attempt to win their first Liam McCarthy Cup since all the way back in 1973. However, the wait would go on… until it was ended gloriously in 2018.The final in Croke Park turned out to be an anti-climax for Treaty supporters as they fell to the all conquering Kilkenny on a scoreline of 2-19 to 1-15.

Framed photo of the gallant 2007 Limerick Hurlers who reached the All Ireland final where they were beaten by an all time great Kilkenny Team. 53cm x 68cm Limerick In 2007, Limerick shook up the hurling landscape by reaching their first All Ireland final since 1996 in an attempt to win their first Liam McCarthy Cup since all the way back in 1973. However, the wait would go on… until it was ended gloriously in 2018.The final in Croke Park turned out to be an anti-climax for Treaty supporters as they fell to the all conquering Kilkenny on a scoreline of 2-19 to 1-15. However, the Limerick players of 2007 will go down as heroes on Shannonside, regardless of a sub-standard performance on the first Sunday of September.

After an epic Munster championship, which saw Richie Bennis’s side go to two replays with Tipperary, eventually coming out on top after extra-time in the third game before succumbing to a Dan Shanahan inspired Waterford in the final, Limerick went on to gather a momentum that would see them all the way to a clash with Brian Cody’s charges with the All Ireland title on the line.

However, the Limerick players of 2007 will go down as heroes on Shannonside, regardless of a sub-standard performance on the first Sunday of September.

After an epic Munster championship, which saw Richie Bennis’s side go to two replays with Tipperary, eventually coming out on top after extra-time in the third game before succumbing to a Dan Shanahan inspired Waterford in the final, Limerick went on to gather a momentum that would see them all the way to a clash with Brian Cody’s charges with the All Ireland title on the line.

Henry Shefflin was the Cats captain that year and notched 1-2 for himself on the big day, while Eddie Brennan top-scored with a tally of 1-5.

Henry Shefflin was the Cats captain that year and notched 1-2 for himself on the big day, while Eddie Brennan top-scored with a tally of 1-5.

-

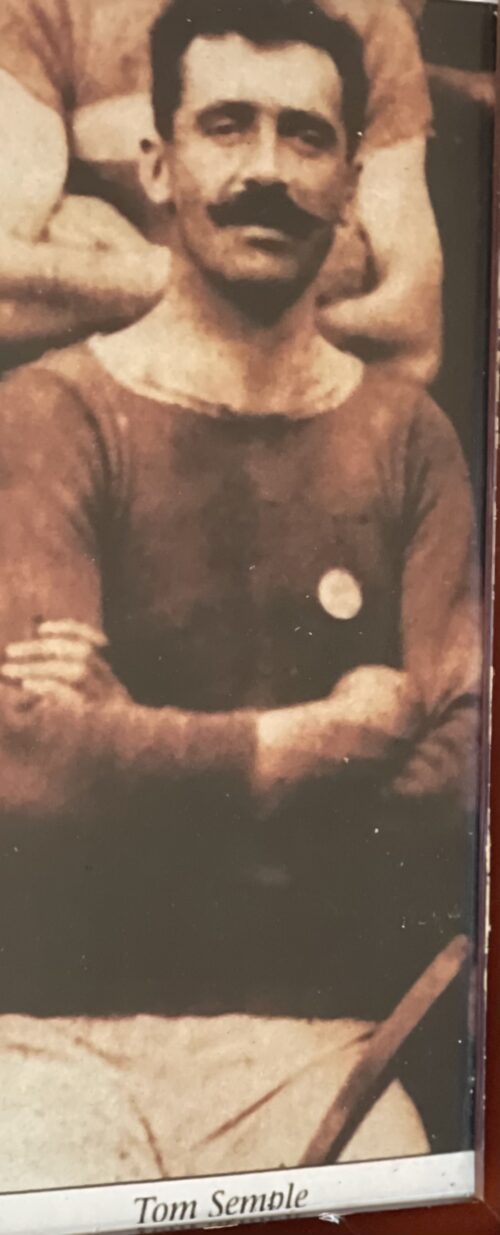

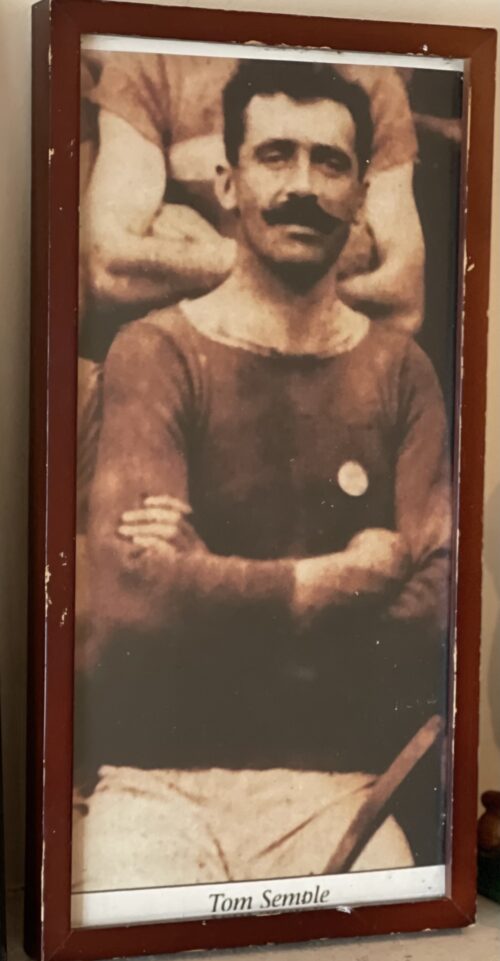

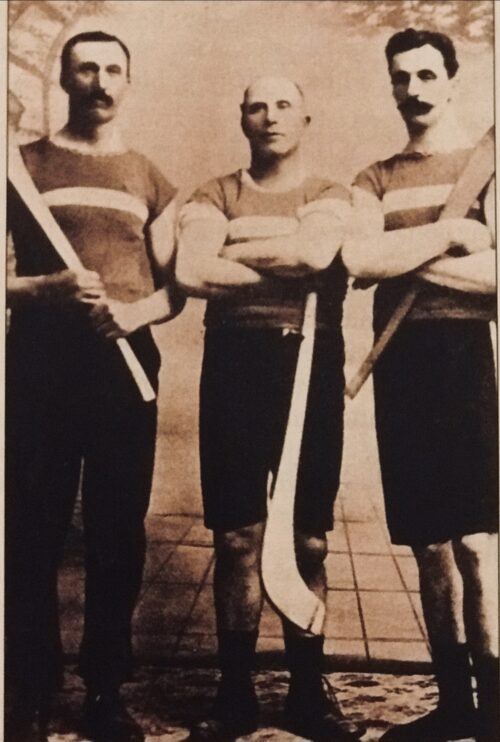

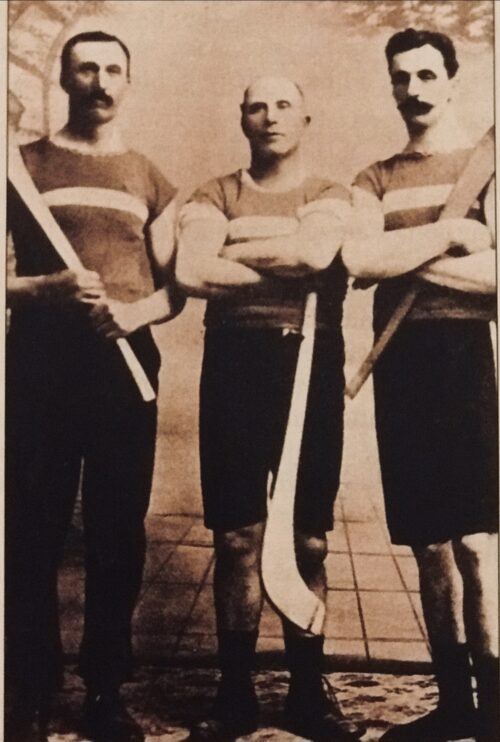

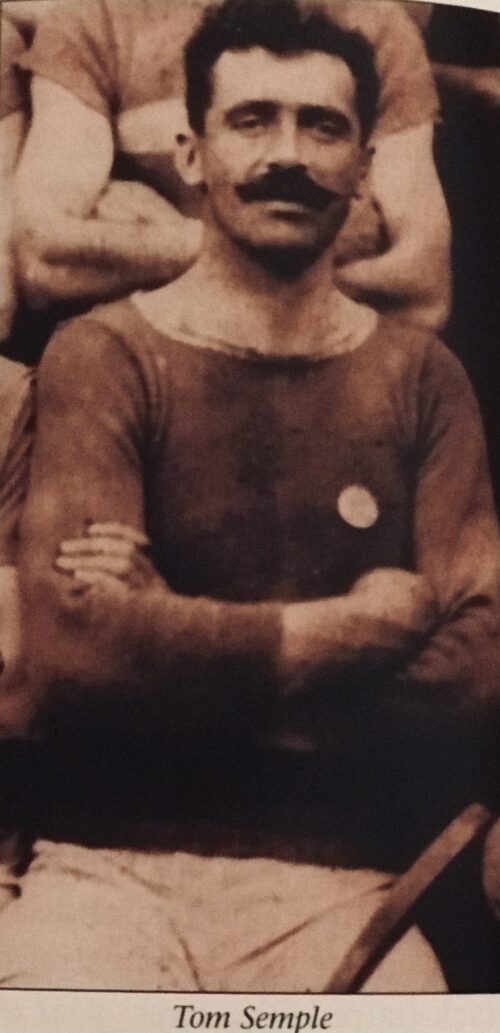

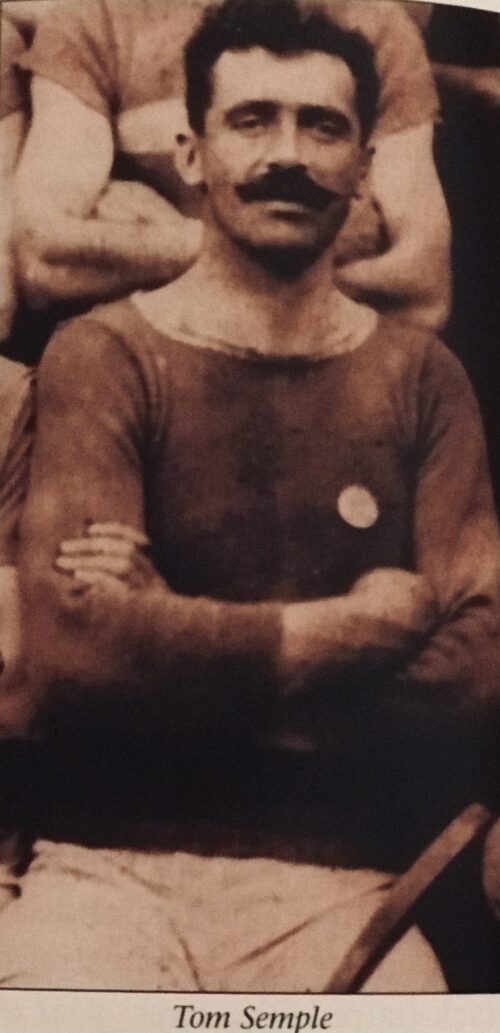

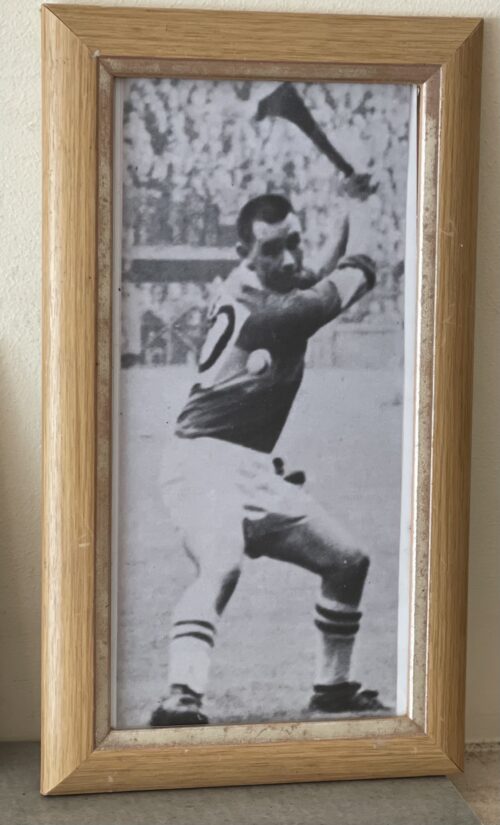

Great portrait of Tipperary Hurling Legend Tom Semple of Thurles 47cm x 24cm Thurles Co Tipperary Thomas Semple (8 April 1879 – 11 April 1943) was an Irish hurler who played as a half-forward for the Tipperary senior team. Semple joined the panel during the 1897 championship and eventually became a regular member of the starting seventeen until his retirement after the 1909 championship. During that time he won three All-Ireland medals and four Munster medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on one occasion, Semple captained the team to the All-Ireland title in 1906 and in 1908. At club level Semple was a six-time county club championship medalist with Thurles. Semple played his club hurling with the local club in Thurles, the precursor to the famous Sarsfield's club. He rose through the club and served as captain of the team for almost a decade. In 1904 Semple won his first championship medal following a walkover from Lahorna De Wets. Thurles failed to retain their title, however, the team returned to the championship decider once again in 1906. A 4-11 to 3-6 defeat of Lahorna De Wets gave Semple his second championship medal as captain. It was the first of four successive championships for Thurles as subsequent defeats of Lahorna De Wets, Glengoole and Racecourse/Grangemockler brought Semple's medal tally to five. Five-in-a-row proved beyond Thurles, however, Semple's team reached the final for the sixth time in eight seasons in 1911. A 4-5 to 1-0 trouncing of Toomevara gave Semple his sixth and final championship medal as captain.

Great portrait of Tipperary Hurling Legend Tom Semple of Thurles 47cm x 24cm Thurles Co Tipperary Thomas Semple (8 April 1879 – 11 April 1943) was an Irish hurler who played as a half-forward for the Tipperary senior team. Semple joined the panel during the 1897 championship and eventually became a regular member of the starting seventeen until his retirement after the 1909 championship. During that time he won three All-Ireland medals and four Munster medals. An All-Ireland runner-up on one occasion, Semple captained the team to the All-Ireland title in 1906 and in 1908. At club level Semple was a six-time county club championship medalist with Thurles. Semple played his club hurling with the local club in Thurles, the precursor to the famous Sarsfield's club. He rose through the club and served as captain of the team for almost a decade. In 1904 Semple won his first championship medal following a walkover from Lahorna De Wets. Thurles failed to retain their title, however, the team returned to the championship decider once again in 1906. A 4-11 to 3-6 defeat of Lahorna De Wets gave Semple his second championship medal as captain. It was the first of four successive championships for Thurles as subsequent defeats of Lahorna De Wets, Glengoole and Racecourse/Grangemockler brought Semple's medal tally to five. Five-in-a-row proved beyond Thurles, however, Semple's team reached the final for the sixth time in eight seasons in 1911. A 4-5 to 1-0 trouncing of Toomevara gave Semple his sixth and final championship medal as captain.Inter-county

Semple's skill quickly brought him to the attention of the Tipperary senior hurling selectors. After briefly joining the team in 1897, he had to wait until 1900 to become a regular member of the starting seventeen. That year a 6-11 to 1-9 trouncing of Kerry gave him his first Munster medal.Tipp later narrowly defeated Kilkenny in the All-Ireland semi-final before trouncing Galway in the "home" All-Ireland final. This was not the end of the championship campaign because, for the first year ever, the "home" finalists had to take on London in the All-Ireland decider. The game was a close affair with both sides level at five points with eight minutes to go. London then took the lead; however, they later conceded a free. Tipp's Mikey Maher stepped up, took the free and a forward charge carried the sliotar over the line. Tipp scored another goal following a weak puck out and claimed a 2-5 to 0-6 victory.It was Semple's first All-Ireland medal. Cork dominated the provincial championship for the next five years; however, Tipp bounced back in 1906. That year Semple was captain for the first time as Tipp foiled Cork's bid for an unprecedented sixth Munster title in-a-row. The score line of 3-4 to 0-9 gave Semple a second Munster medal. Tipp trounced Galway by 7-14 to 0-2 on their next outing, setting up an All-Ireland final meeting with Dublin. Semple's side got off to a bad start with Dublin's Bill Leonard scoring a goal after just five seconds of play. Tipp fought back with Paddy Riordan giving an exceptional display of hurling and capturing most of his team's scores. Ironically, eleven members of the Dublin team hailed from Tipperary. The final score of 3-16 to 3-8 gave victory to Tipperary and gave Semple a second All-Ireland medal. Tipp lost their provincial crown in 1907, however, they reached the Munster final again in 1908. Semple was captain of the side again that year as his team received a walkover from Kerry in the provincial decider. Another defeat of Galway in the penultimate game set up another All-Ireland final meeting with Dublin. That game ended in a 2-5 to 1-8 draw and a replay was staged several months later in Athy. Semple's team were much sharper on that occasion. A first-half goal by Hugh Shelly put Tipp well on their way. Two more goals by Tony Carew after the interval gave Tipp a 3-15 to 1-5 victory.It was Semple's third All-Ireland medal. 1909 saw Tipp defeat arch rivals Cork in the Munster final once again. A 2-10 to 1-6 victory gave Semple his fourth Munster medal. The subsequent All-Ireland final saw Tipp take on Kilkenny. The omens looked good for a Tipperary win. It was the county's ninth appearance in the championship decider and they had won the previous eight. All did not go to plan as this Kilkenny side cemented their reputation as the team of the decade. A 4-6 to 0-12 defeat gave victory to "the Cats" and a first final defeat to Tipperary. Semple retired from inter-county hurling following this defeat. Semple was born in Drombane, County Tipperary in 1879. He received a limited education at his local national school and, like many of his contemporaries, finding work was a difficult prospect. At the age of 16 Semple left his native area and moved to Thurles. Here he worked as a guardsman with the Great Southern & Western Railway. In retirement from playing Semple maintained a keen interest in Gaelic games. In 1910 he and others organised a committee which purchased the showgrounds in Thurles in an effort to develop a hurling playing field there. This later became known as Thurles Sportsfield and is regarded as one of the best surfaces for hurling in Ireland. In 1971 it was renamed Semple Stadium in his honour. The stadium is also lovingly referred to as Tom Semple's field. Semple also held the post of chairman of the Tipperary County Board and represented the Tipperary on the Munster Council and Central Council. He also served as treasurer of the latter organization. During the War of Independence Semple played an important role for Republicans. He organized dispatches via his position with the Great Southern & Western Railway in Thurles. Tom Semple died on 11 April 1943 Tipperary Hurling Team outside Clonmel railway station, August 26, 1910. Semple is in the centre of the middle row.

Tipperary Hurling Team outside Clonmel railway station, August 26, 1910. Semple is in the centre of the middle row. -

35cm x 50cm Limerick

35cm x 50cm Limerickloody Sunday, 21st November 1920

In 1920 the War of Independence was ongoing in Ireland.

On the morning of November 21st, an elite assassination unit known as ‘The Squad’ mounted an operation planned by Michael Collins, Director of Intelligence of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Their orders were clear – they were to take out the backbone of the British Intelligence network in Ireland, specifically a group of officers known as ‘The Cairo Gang’. The shootings took place in and around Dublin’s south inner city and resulted in fourteen deaths, including six intelligence agents and two members of the British Auxiliary Force. Later that afternoon, Dublin were scheduled to play Tipperary in a one-off challenge match at Croke Park, the proceeds of which were in aid of the Republican Prisoners Dependents Fund. Tensions were high in Dublin due to fears of a reprisal by Crown forces following the assassinations. Despite this a crowd of almost 10,000 gathered in Croke Park. Throw-in was scheduled for 2.45pm, but it did not start until 3.15pm as crowd congestion caused a delay.Eye-witness accounts suggest that five minutes after the throw-in an aeroplane flew over Croke Park. It circled the ground twice and shot a red flare - a signal to a mixed force of Royal Irish Constabulary (R.I.C.), Auxiliary Police and Military who then stormed into Croke Park and opened fire on the crowd. Amongst the spectators, there was a rush to all four exits, but the army stopped people from leaving the ground and this created a series of crushes around the stadium. Along the Cusack Stand side, hundreds of people braved the twenty-foot drop and jumped into the adjacent Belvedere Sports Grounds. The shooting lasted for less than two minutes. That afternoon in Croke Park, 14 people including one player (Michael Hogan from Tipperary), lost their lives. It is estimated that 60 – 100 people were injured. Dublin Team, Bloody Sunday 1920The names of those who died in Croke Park on Bloody Sunday 1920 were. James Burke, Jane Boyle, Daniel Carroll, Michael Feery, Michael Hogan, Thomas (Tom) Hogan, James Matthews, Patrick O’Dowd, Jerome O’Leary, William (Perry) Robinson, Tom Ryan, John William (Billy) Scott, James Teehan, Joseph Traynor. In 1925, the GAA's Central Council took the decision to name a stand in Croke Park after Michael Hogan. The 21st November 2020 marks one hundred years since the events of Bloody Sunday in Croke Park.

Dublin Team, Bloody Sunday 1920The names of those who died in Croke Park on Bloody Sunday 1920 were. James Burke, Jane Boyle, Daniel Carroll, Michael Feery, Michael Hogan, Thomas (Tom) Hogan, James Matthews, Patrick O’Dowd, Jerome O’Leary, William (Perry) Robinson, Tom Ryan, John William (Billy) Scott, James Teehan, Joseph Traynor. In 1925, the GAA's Central Council took the decision to name a stand in Croke Park after Michael Hogan. The 21st November 2020 marks one hundred years since the events of Bloody Sunday in Croke Park. Tipperary Team, Bloody Sunday 1920

Tipperary Team, Bloody Sunday 1920 Michael Hogan

Michael Hogan -

Tullamore Dew advert 40cm x 30cm Banagher Co Offaly Tullamore D.E.W. is a brand of Irish whiskey produced by William Grant & Sons. It is the second largest selling brand of Irish whiskey globally, with sales of over 950,000 cases per annum as of 2015.The whiskey was originally produced in the Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland, at the old Tullamore Distillery which was established in 1829. Its name is derived from the initials of Daniel E. Williams (D.E.W.), a general manager and later owner of the original distillery. In 1954, the original distillery closed down, and with stocks of whiskey running low, the brand was sold to John Powers & Son, another Irish distiller in the 1960s, with production transferred to the Midleton Distillery, County Cork in the 1970s following a merger of three major Irish distillers.In 2010, the brand was purchased by William Grant & Sons, who constructed a new distillery on the outskirts of Tullamore. The new distillery opened in 2014, bringing production of the whiskey back to the town after a break of sixty years.

Tullamore Dew advert 40cm x 30cm Banagher Co Offaly Tullamore D.E.W. is a brand of Irish whiskey produced by William Grant & Sons. It is the second largest selling brand of Irish whiskey globally, with sales of over 950,000 cases per annum as of 2015.The whiskey was originally produced in the Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland, at the old Tullamore Distillery which was established in 1829. Its name is derived from the initials of Daniel E. Williams (D.E.W.), a general manager and later owner of the original distillery. In 1954, the original distillery closed down, and with stocks of whiskey running low, the brand was sold to John Powers & Son, another Irish distiller in the 1960s, with production transferred to the Midleton Distillery, County Cork in the 1970s following a merger of three major Irish distillers.In 2010, the brand was purchased by William Grant & Sons, who constructed a new distillery on the outskirts of Tullamore. The new distillery opened in 2014, bringing production of the whiskey back to the town after a break of sixty years.Mick The Miller,as featured in this iconic advert, was the most famous greyhound of all time. He was born in 1926 in the village of Killeigh, County Offaly, Ireland at Millbrook House(only 5 miles from Tullamore), the home of parish curate, Fr Martin Brophy. When he was born Mick was the runt of the litter but Michael Greene, who worked for Fr Brophy, singled the little pup out as a future champion and insisted that he be allowed to rear him. With constant attention and regular exercise Mick The Miller developed into a racing machine. His first forays were on local coursing fields where he had some success but he showed his real talent on the track where he won 15 of his first 20 races.

.jpg)

In 1929 Fr Brophy decided to try Mick in English Greyhound Derby at White City, London. On his first trial-run, Mick equalled the track record. Then, in his first heat, he broke the world record, becoming the first greyhound ever to run 525 yards in under 30 seconds. Fr Brophy was inundated with offers and sold him to Albert Williams. Mick went on to win the 1929 Derby. Within a year he had changed hands again to Arundel H Kempton and won the Derby for a second time.

Over the course of his English career he won 36 of his 48 races, including the Derby (twice), the St Leger, the Cesarewitch, and the Welsh Derby. He set six new world records and two new track records. He was the first greyhound to win 19 races in a row. Several of his records went unbroken for over 40 years. He won, in total, almost £10,000 in prizemoney. But he also became the poster-dog for greyhound racing. He was a celebrity on a par with any sports person, muscisian or moviestar. The more famous he became, the more he attracted people to greyhound racing. Thousands thronged to watch him, providing a huge boost to the sport. It is said that he actually saved the sport of greyhound racing.

After retirement to stud his popularity continued. He starred in the film Wild Boy (based on his life-story) in 1934 which was shown in cinemas all across the UK. He was in huge demand on the celebrity circuit, opening shops, attending big races and even rubbing shoulder with royalty (such as the King and Queen) at charity events. When he died in 1939 aged 12, his owner donated his body to the British Natural History Museum in London. And Mick`s fame has continued ever since. In 1981 he was inducted into the American Hall of Fame (International Section). In 1990 English author Michael Tanner published a book, Mick The Miller - Sporting Icon Of the Depression. And in 2011 the people of Killeigh erected a monument on the village green to honour their most famous son. Mick The Miller is not just the most famous greyhound of all time but one of the most loved dogs that has ever lived.

-

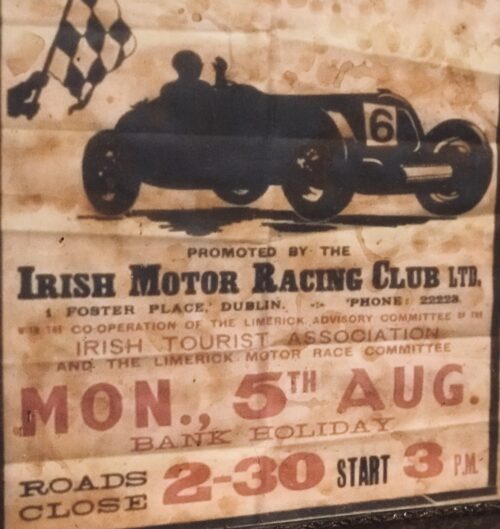

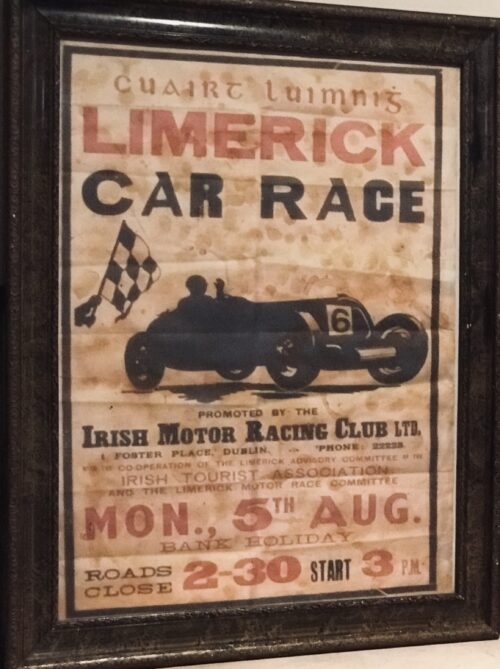

65cm x 50cm Limerick Vintage advertising poster advertising a car racing in Limerick in 1929 to be held around the city and organised by the Irish Motor Racing Club Ltd ,based in Foster Place Dublin. People, like this writer, who do not even have a driving licence find it very difficult to understand the extraordinary interest in motor racing which has mushroomed over the last few years. This newspaper and others have expanded coverage of the sport in a big way and that can only be partly explained by the fact that a young Irishman, Eddie Irvine, has made significant progress in the drivers' championship and that Dubliner Eddie Jordan has a team competing in the constructors' championship. There is a very long and distinguished history of motor racing in Ireland, going back to the turn of the century and before. Irish motorists have contributed profoundly to the popularity of motor racing history. In this context, names like Dunlop and Ferguson immediately spring to mind. The Belfast businessman John Boyd Dunlop first hit upon the idea of a pneumatic tyre when he was trying to entice his son to continue what he considered to be a healthy bicycling pursuit. When Dunlop's tyres helped to wipe out all competition in a Belfast sports meeting in Easter 1889, the invention sparked an idea in the mind of a Dublin businessman called Harvey du Cros - a Huguenot who had fled Roman Catholic persecution in his native France to flee to, of all places, Dublin. The Huguenot refugee had several distinctions. He was a boxing and fencing champion in his day and a founder member of Bective Rangers rugby club. Whether he would have been proud of the latter achievement today cannot be assessed. (Just a joke lads.) He set up a factory for the manufacture of tyres in Stephen Street in Dublin just before the turn of the century and, in doing so, made an enormous contribution to the revolution of transport in the world. The name of Dunlop remains synonymous with tyres, but, sadly, the name du Cros is seldom mentioned. Nevertheless he holds the major French decoration of Legion d'honneur.Mineral waters, normally costing tuppence, were offered at sixpence, but then what else is new! Local farmers' wives also made "a killing" by releasing their hens onto the practice roads and then demanding compensation when they were killed by the speeding cars. Readers may ask how come this writer has taken so much interest in this matter without ever having driven anything faster than a tractor. The reason is that, by chance, I came across a book some time ago called Green Dust, by Brendan Lynch, and was immediately captivated, not only by the tales he told and the manner of the telling, but by the picture of Ireland which Lynch painted. What I see of motor racing on television nowadays bores me to tears, but Brendan Lynch's book is in a different category altogether. As far as I know it is out of print. Could I humbly suggest that he and the publishers, Portobello Publishing, reprint this sporting treasure.The Shannon Development Company of 1900 was the first organisation to promote a motor race in Ireland. The company had built a hotel in Killaloe and organised a motor trip from Dublin to that lovely Clare town, via Nenagh. A De Dion brand car, driven by L Fleming, was first to enter Killaloe in July of 1900. James Gordon Bennett, the American millionaire who had sent Stanley in pursuit of Livingston, offered the first major trophy for motor racing. There was a reluctance to allow this very dangerous sport to be held in Britain and the matter was referred to the House of Commons when an extraordinary alliance involving John Redmond, Tim Healy and Sir Edward Carson all supported the idea that speed limits should be set aside for that day. The Northern Whig said: "We see a wonderful blending of the Orange and Green. There is, about this matter, a unanimity of which some people considered Irishmen to be incapable." Could we, perhaps, arrange a Drumcree Grand Prix! With the blessing of the Bishop of Kildare, a circuit centred on Athy was agreed for Ireland's first serious motor road race which took place on July 2nd, a public holiday, in 1903. The race started just north of Athy and on a figure of eight circuit, the competitors drove 327 miles, going through such exotic places as Kilcullen, Castledermot, Carlow, Monasterevin, Stradbally and Windy Gap. In the build up to the race, James Joyce earned a few badly needed shillings by interviewing the top French driver of the day, Henri Fournier, in The Irish Times. Drivers from all over Europe and the United States took part and prices went through the ceiling as foreign drivers, mechanics, and spectators descended on Athy and its environs. There was one report of £50 being charged for two rooms in Kilcullen for one night, a charge which might, even today, be regarded as a little pricey.

65cm x 50cm Limerick Vintage advertising poster advertising a car racing in Limerick in 1929 to be held around the city and organised by the Irish Motor Racing Club Ltd ,based in Foster Place Dublin. People, like this writer, who do not even have a driving licence find it very difficult to understand the extraordinary interest in motor racing which has mushroomed over the last few years. This newspaper and others have expanded coverage of the sport in a big way and that can only be partly explained by the fact that a young Irishman, Eddie Irvine, has made significant progress in the drivers' championship and that Dubliner Eddie Jordan has a team competing in the constructors' championship. There is a very long and distinguished history of motor racing in Ireland, going back to the turn of the century and before. Irish motorists have contributed profoundly to the popularity of motor racing history. In this context, names like Dunlop and Ferguson immediately spring to mind. The Belfast businessman John Boyd Dunlop first hit upon the idea of a pneumatic tyre when he was trying to entice his son to continue what he considered to be a healthy bicycling pursuit. When Dunlop's tyres helped to wipe out all competition in a Belfast sports meeting in Easter 1889, the invention sparked an idea in the mind of a Dublin businessman called Harvey du Cros - a Huguenot who had fled Roman Catholic persecution in his native France to flee to, of all places, Dublin. The Huguenot refugee had several distinctions. He was a boxing and fencing champion in his day and a founder member of Bective Rangers rugby club. Whether he would have been proud of the latter achievement today cannot be assessed. (Just a joke lads.) He set up a factory for the manufacture of tyres in Stephen Street in Dublin just before the turn of the century and, in doing so, made an enormous contribution to the revolution of transport in the world. The name of Dunlop remains synonymous with tyres, but, sadly, the name du Cros is seldom mentioned. Nevertheless he holds the major French decoration of Legion d'honneur.Mineral waters, normally costing tuppence, were offered at sixpence, but then what else is new! Local farmers' wives also made "a killing" by releasing their hens onto the practice roads and then demanding compensation when they were killed by the speeding cars. Readers may ask how come this writer has taken so much interest in this matter without ever having driven anything faster than a tractor. The reason is that, by chance, I came across a book some time ago called Green Dust, by Brendan Lynch, and was immediately captivated, not only by the tales he told and the manner of the telling, but by the picture of Ireland which Lynch painted. What I see of motor racing on television nowadays bores me to tears, but Brendan Lynch's book is in a different category altogether. As far as I know it is out of print. Could I humbly suggest that he and the publishers, Portobello Publishing, reprint this sporting treasure.The Shannon Development Company of 1900 was the first organisation to promote a motor race in Ireland. The company had built a hotel in Killaloe and organised a motor trip from Dublin to that lovely Clare town, via Nenagh. A De Dion brand car, driven by L Fleming, was first to enter Killaloe in July of 1900. James Gordon Bennett, the American millionaire who had sent Stanley in pursuit of Livingston, offered the first major trophy for motor racing. There was a reluctance to allow this very dangerous sport to be held in Britain and the matter was referred to the House of Commons when an extraordinary alliance involving John Redmond, Tim Healy and Sir Edward Carson all supported the idea that speed limits should be set aside for that day. The Northern Whig said: "We see a wonderful blending of the Orange and Green. There is, about this matter, a unanimity of which some people considered Irishmen to be incapable." Could we, perhaps, arrange a Drumcree Grand Prix! With the blessing of the Bishop of Kildare, a circuit centred on Athy was agreed for Ireland's first serious motor road race which took place on July 2nd, a public holiday, in 1903. The race started just north of Athy and on a figure of eight circuit, the competitors drove 327 miles, going through such exotic places as Kilcullen, Castledermot, Carlow, Monasterevin, Stradbally and Windy Gap. In the build up to the race, James Joyce earned a few badly needed shillings by interviewing the top French driver of the day, Henri Fournier, in The Irish Times. Drivers from all over Europe and the United States took part and prices went through the ceiling as foreign drivers, mechanics, and spectators descended on Athy and its environs. There was one report of £50 being charged for two rooms in Kilcullen for one night, a charge which might, even today, be regarded as a little pricey. -

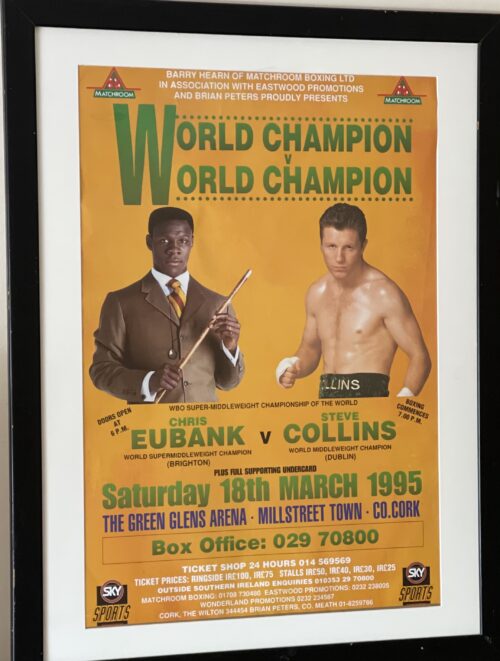

Framed Fight poster of Collins v Eubank at Millstreet 1995. 90cm x 68cm Co Cork Stephen Collins (born 21 July 1964) is an Irish former professional boxer who competed from 1986 to 1997. Known as the Celtic Warrior, Collins is the most successful Irish boxer in recent professional boxing history, having held the WBOmiddleweight and super-middleweight titles simultaneously and never losing a fight as champion. Collins' first nineteen professional fights all took place in the United States. In 1988 he won the Irish middleweight title, and the regional American USBA middleweight title the following year, defending the latter successfully in Atlantic City and Las Vegas. In his first two world championship challenges, both for the WBA middleweight title, Collins lost a unanimous decision to Mike McCallum in 1990 and a majority decision to Reggie Johnson in 1992. He also challenged unsuccessfully for the European middleweight title later in 1992, losing a split decision to Sumbu Kalambay in Italy. It was not until Collins reached his early 30s that he fulfilled his potential, becoming WBO middleweight champion in his third world title attempt with a fifth-round TKO victory over Chris Pyatt in 1994, before then moving up in weight to defeat the undefeated Chris Eubank and claim the WBO super-middleweight title in 1995. More success followed, as Collins successfully defended his title by winning the rematch against Eubank later in the year. Collins successfully defended his title another six times before pulling out of a proposed fight in October 1997 against rising Welsh star, Joe Calzaghe, and retiring from the sport, with Collins frustrated by his inability to get a fight against the pound for pound number one boxer of the time, Roy Jones Jr., who was then fighting in the light-heavyweight division. Having competed against some of the best boxers on both sides of the Atlantic during his career, Collins tends to be linked more to an era in the UK during which there was a notable rivalry between British boxers Chris Eubank and Nigel Benn, both of whom Collins fought and defeated twice.

Framed Fight poster of Collins v Eubank at Millstreet 1995. 90cm x 68cm Co Cork Stephen Collins (born 21 July 1964) is an Irish former professional boxer who competed from 1986 to 1997. Known as the Celtic Warrior, Collins is the most successful Irish boxer in recent professional boxing history, having held the WBOmiddleweight and super-middleweight titles simultaneously and never losing a fight as champion. Collins' first nineteen professional fights all took place in the United States. In 1988 he won the Irish middleweight title, and the regional American USBA middleweight title the following year, defending the latter successfully in Atlantic City and Las Vegas. In his first two world championship challenges, both for the WBA middleweight title, Collins lost a unanimous decision to Mike McCallum in 1990 and a majority decision to Reggie Johnson in 1992. He also challenged unsuccessfully for the European middleweight title later in 1992, losing a split decision to Sumbu Kalambay in Italy. It was not until Collins reached his early 30s that he fulfilled his potential, becoming WBO middleweight champion in his third world title attempt with a fifth-round TKO victory over Chris Pyatt in 1994, before then moving up in weight to defeat the undefeated Chris Eubank and claim the WBO super-middleweight title in 1995. More success followed, as Collins successfully defended his title by winning the rematch against Eubank later in the year. Collins successfully defended his title another six times before pulling out of a proposed fight in October 1997 against rising Welsh star, Joe Calzaghe, and retiring from the sport, with Collins frustrated by his inability to get a fight against the pound for pound number one boxer of the time, Roy Jones Jr., who was then fighting in the light-heavyweight division. Having competed against some of the best boxers on both sides of the Atlantic during his career, Collins tends to be linked more to an era in the UK during which there was a notable rivalry between British boxers Chris Eubank and Nigel Benn, both of whom Collins fought and defeated twice.Early years in Boston

Steve Collins won 26 Irish titles as an amateur before turning professional in Massachusetts, US in October 1986. Collins worked out of the Petronelli Brothers gym in Brockton, Massachusetts alongside Marvin Hagler. His debut fight was against Julio Mercado on the undercard of a bill that featured Irish Americans; his future trainer Freddie Roach and the future Fight of the Year winner Micky Ward. Collins beat Mercado by way of knockout in the third round. In Boston, Massachusetts in 1988, he defeated former Olympian and British Super Middleweight champion Sam Storey to win the Irish middleweight title, then defeated world No. 5, Kevin Watts to win the USBA middleweight title. After reaching 16–0, Collins stepped in as a substitute in a WBA middleweight title fight after Michael Watson was injured in training, and fought 12 rounds against Mike McCallum in Boston in 1990. Collins was supported by a large crowd of Irish Americans as he battled the champion McCallum, with the fight being close early on before McCallum started to tire as Collins gained momentum in the later stages to bring a close finish at the end of 12 exciting rounds. McCallum got the win by unanimous decision. In 1992, Collins lost a majority decision to Reggie Johnson in a closely contested slugfest for the vacant WBA middleweight title (which had been stripped from McCallum because he signed to fight IBF champion James Toney). Collins then lost by split decision to Sumbu Kalambay for the European title in Italy, before beating Gerhard Botes of South Africa to win the WBA Penta-Continental middleweight title in 1993.WBO middleweight champion

Collins then moved to Belfast under the management of Barney Eastwood before basing himself in England where he joined Barry Hearn's Matchroom Boxing. Alongside him was Paul "Silky" Jones, his sparring partner and good friend who later went on to become WBO light-middleweight title holder. Collins was trained by Freddie King in the Romford training camp. In May 1994, Collins finally won a world title by defeating Chris Pyatt by stoppage in five rounds to become the WBO middleweight champion. Early in 1995, Collins relinquished this title without a defence as he was having difficulty making the 160lbs middleweight limit. In March 1995, Chris Eubank (41-0-2) had been scheduled to have a third WBO super-middleweight title fight against Ray Close. Eubank and Close had two fights over the previous two years (their first fight a draw, and their second fight a narrow split decision win for Eubank), but Close was forced to withdraw from their scheduled third fight after failing an MRI brain scan. Collins then stepped into Close's place, moving up to super-middleweight to take on Eubank.WBO super-middleweight champion

Collins defeated the then unbeaten long-reigning champion Chris Eubank in Millstreet, County Cork, Ireland, in March 1995, by unanimous decision (115–111, 116–114, 114–113), to win the WBO super-middleweight title. Collins had enlisted the help of a guru, and they led the press to believe that Collins would be hypnotised for the fight, which noticeably unsettled Eubank. True to form, Collins sat in his corner and did not move, listening to headphones during Eubank's ring entrance. Collins knocked Eubank down in the eighth round, and was well ahead on the scorecards at the end of Round 9, but Eubank finished the fight strongly as he tried to save his unbeaten record and knocked Collins down in the tenth round, coming close to a stoppage. Eubank was unable to finish the job, and Collins held on for victory. In their September 1995 rematch in Cork, Collins performed brilliantly, changing his usual fighting style by adopting wild, brawling tactics throughout which Eubank really struggled to deal with. Despite most TV pundits and commentators giving Collins a wide points victory with scorecards in the region of 117–111 and 118–110, the three judges saw the fight very differently with Collins only winning by a close split decision, 115–113, 115–113 and 114–115. Collins successfully defended his WBO super-middleweight title seven times, including two fights against Nigel Benn in 1996. In the summer of 1997, Collins reportedly stated in the press that he had no motivation left, as he had spent the best part of his career chasing Roy Jones Jr. for a fight that had been promised to him many times. Collins is reported to have stated in Boxing World that he had spent so long chasing Roy Jones Jr. that money was no longer important; that he would "fight him in a phone box in front of two men and a dog". but the bout never materialised. A WBO super-middleweight title fight against Joe Calzaghe was agreed for October 1997, but Collins got injured 10 days before the scheduled fight, got stripped of his title by the WBO, with Collins then making a statement saying that fighting Calzaghe would do nothing to satisfy the desire he had for fighting Jones. Collins then added he wanted to retire on a high note with a good pay day, "Joe is a good up-and-coming kid, but he wouldn't fill a parish church". As Collins couldn't get the fight with Jones, Collins decided to retire. In 1999, Collins announced his decision to come out of retirement to fight Roy Jones Jr. Controversy surrounded the proposed fight, as WBC and WBA light heavyweight champion Jones decided to fight the IBF light heavyweight champion and old Collins foe Reggie Johnson (which Jones won by a shutout 120–106 on all three judges' scorecards), and it was revealed that Collins would have to fight Calzaghe before a showdown with Jones. Collins had accepted this and started to prepare to fight Calzaghe. In training, Collins collapsed during a sparring session with Howard Eastman. Although tests and a brain scan could not find any problems, Collins decided that it was a warning to make him stop boxing, and he retired for a second time. Collins retired in 1997, with a record of 39 fights, 36 wins (21 knockouts) and 3 losses. Collins has not entirely faded from the spotlight since his retirement. In 1998 he appeared in the film Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels as a boxing gym bouncer. In 1999 he made a cameo appearance in "Sweetest Thing", a music video by U2. On 15 January 2013, at the age of 48, Collins announced plans to fight Roy Jones Jr.He went on to appear in a number of exhibition bouts in preparation for the proposed Jones fight. In 2017 Collins joined the Army Reserve's 253 Provost Company of the 4th Regiment Royal Military Police in London where he had been living for the previous 20 years. He gained promotion to Lance Corporal and qualified as an army boxing coach. His brother Roddy Collins is a former professional footballer and manager. His brother Paschal was a professional boxer and now a leading professional boxing coach plus manager. His eldest son Stevie Jnr is a retired rugby player and a retired professional boxer who now coaches and manages boxers His youngest son Luke is an active amateur boxer and qualified amateur boxing coach -

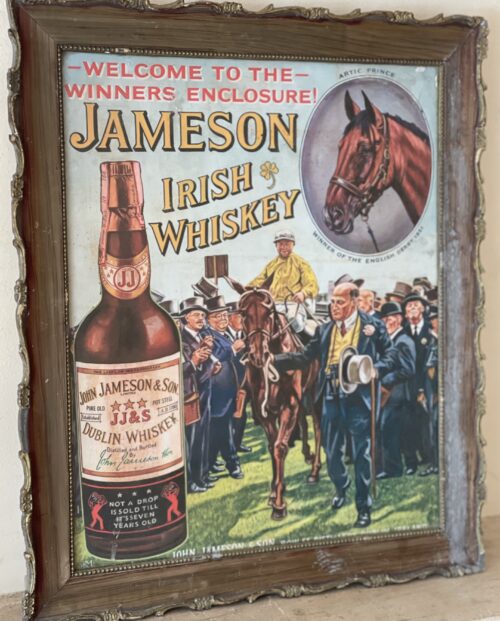

Classic Jameson Irish Whiskey Horse Racing advertisement from 1951 with a picture of the Epsom Derby winner Arctic Prince being led into the winners enclosure by his proud owner,Irish businessman and Founder of the Irish Hospital Sweepstakes ,Mr Joe McGrath. 50cm x 43cm. Dublin Joseph McGrath ( 12 August 1888 – 26 March 1966) was an Irish politician and businessman.He was a Sinn Féin and later a Cumann na nGaedheal Teachta Dála (TD) for various constituencies Dublin St James's (1918–21) Dublin North West (1921–23) and Mayo North (1923–27) and developed widespread business interests. McGrath was born in Dublin in 1888. By 1916 he was working with his brother George at Craig Gardiner & Co, a firm of accountants in Dawson Street, Dublin. He worked with Michael Collins, a part-time fellow clerk and the two struck up a friendship. In his spare time McGrath worked as secretary for the Volunteer Dependents' Fund. He soon joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood. He fought in Marrowbone Lane in the 1916 Easter Rising. McGrath was arrested after the rising, and jailed in Wormwood Scrubs and Brixton prisons in England. In the 1918 general election, he was elected as Sinn Féin TD for the Dublin St James's constituency, later sitting in the First Dáil.He was also a member of the Irish Republican Army, the guerrilla army of the Irish Republic, and successfully organised many bank robberies during the Irish war of Independence (1919–1921), where a small percentage of the proceeds was retained as a reward by him and his fellow-soldiers.During this time he was interred briefly at Ballykinlar Internment Camp. He escaped by dressing in army uniform and walking out of the gate with soldiers going on leave. He was eventually recaptured and spent time in jail in Belfast. In October 1921 McGrath travelled with the Irish Treaty delegation to London as one of Michael Collins' personal staff. When the Provisional Government of Ireland was set up in January 1922, McGrath was appointed as Minister for Labour. In the Irish Civil War of 1922–1923, he took the pro-treaty side and was made Director of Intelligence, replacing Liam Tobin. In a strongly worded letter, written in red ink, McGrath warned Collins not to take his last, ill-fated trip to Cork. He was later put in charge of the police Intelligence service of the new Irish Free State, the Criminal Investigation Department or CID. It was modelled on the London Metropolitan Police department of the same name, but was accused of the torture and killing of a number of republican (anti-treaty) prisoners during the civil war. It was disbanded at the war's end; the official reason given was that it was unnecessary for a police force in peacetime. McGrath went on to serve as Minister for Labour in the Second Dáil and the Provisional Government of Ireland. He also served in the 1st and 2nd Executive Councils holding the Industry and Commerce portfolio. In September 1922 McGrath used strikebreakers to oppose a strike by Trade Unionists in the Post Office service, despite having threatened to resign in the previous March of the same year when the government threatened to use British strikebreakers-four high profile IRA prisoners; Liam Mellows, Dick Barrett, Rory O'Connor, and Joe McKelvey. McGrath resigned from office in April 1924 because of dissatisfaction with the government's attitude to the Army Mutinyofficers and as he said himself, "government by a clique and by the officialdom of the old regime." By this he meant that former IRA fighters were being overlooked and that the Republican goals on all Ireland had been sidelined. McGrath and eight other TDs who had resigned from Cumann na nGaedheal then resigned their seats in the Dáil and formed a new political party, the National Party. However, the new party did not contest the subsequent by-elections for their old seats. Instead, Cumann na nGaedheal won seven of the seats and Sinn Féin won the other two. In 1927, McGrath took a libel case against the publishers of "The Real Ireland" by poet Cyril Bretherton, a book that claimed McGrath was responsible for the abduction and murder of Noel Lemass (the brother of Seán Lemass) in June 1923 during the Civil war, as well as a subsequent coverup. McGrath won the court case. During the 1930s, McGrath and Seán Lemass reconciled and regularly played poker together. Following his political career, he went on to become involved in the building trade. In 1925 he became labour adviser to Siemens-Schuckert, German contractors for the Ardnacrusha hydro-electric scheme near Limerick. McGrath founded the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstake in 1930, and the success of its sweepstakes made him an extremely wealthy man. He had other extensive and successful business interests always investing in Ireland and became Ireland's best-known racehorse owner and breeder, winning The Derby with Arctic Prince in 1951. McGrath died at his home, Cabinteely House, in Dublin on 26 March 1966. Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986, and the land developed as a public park. Joe's son Paddy McGrath inherited many of his father's business interests, and also served as Fine Gael Senator from 1973 to 1977. John Jameson was originally a lawyer from Alloa in Scotland before he founded his eponymous distillery in Dublin in 1780.Prevoius to this he had made the wise move of marrying Margaret Haig (1753–1815) in 1768,one of the simple reasons being Margaret was the eldest daughter of John Haig, the famous whisky distiller in Scotland. John and Margaret had eight sons and eight daughters, a family of 16 children. Portraits of the couple by Sir Henry Raeburn are on display in the National Gallery of Ireland. John Jameson joined the Convivial Lodge No. 202, of the Dublin Freemasons on the 24th June 1774 and in 1780, Irish whiskey distillation began at Bow Street. In 1805, he was joined by his son John Jameson II who took over the family business that year and for the next 41 years, John Jameson II built up the business before handing over to his son John Jameson the 3rd in 1851. In 1901, the Company was formally incorporated as John Jameson and Son Ltd. Four of John Jameson’s sons followed his footsteps in distilling in Ireland, John Jameson II (1773 – 1851) at Bow Street, William and James Jameson at Marrowbone Lane in Dublin (where they partnered their Stein relations, calling their business Jameson and Stein, before settling on William Jameson & Co.). The fourth of Jameson's sons, Andrew, who had a small distillery at Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, was the grandfather of Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of wireless telegraphy. Marconi’s mother was Annie Jameson, Andrew’s daughter. John Jameson’s eldest son, Robert took over his father’s legal business in Alloa. The Jamesons became the most important distilling family in Ireland, despite rivalry between the Bow Street and Marrowbone Lane distilleries. By the turn of the 19th century, it was the second largest producer in Ireland and one of the largest in the world, producing 1,000,000 gallons annually. Dublin at the time was the centre of world whiskey production. It was the second most popular spirit in the world after rum and internationally Jameson had by 1805 become the world's number one whiskey. Today, Jameson is the world's third largest single-distillery whiskey. Historical events, for a time, set the company back. The temperance movement in Ireland had an enormous impact domestically but the two key events that affected Jameson were the Irish War of Independence and subsequent trade war with the British which denied Jameson the export markets of the Commonwealth, and shortly thereafter, the introduction of prohibition in the United States. While Scottish brands could easily slip across the Canada–US border, Jameson was excluded from its biggest market for many years. The introduction of column stills by the Scottish blenders in the mid-19th-century enabled increased production that the Irish, still making labour-intensive single pot still whiskey, could not compete with. There was a legal enquiry somewhere in 1908 to deal with the trade definition of whiskey. The Scottish producers won within some jurisdictions, and blends became recognised in the law of that jurisdiction as whiskey. The Irish in general, and Jameson in particular, continued with the traditional pot still production process for many years.In 1966 John Jameson merged with Cork Distillers and John Powers to form the Irish Distillers Group. In 1976, the Dublin whiskey distilleries of Jameson in Bow Street and in John's Lane were closed following the opening of a New Midleton Distillery by Irish Distillers outside Cork. The Midleton Distillery now produces much of the Irish whiskey sold in Ireland under the Jameson, Midleton, Powers, Redbreast, Spot and Paddy labels. The new facility adjoins the Old Midleton Distillery, the original home of the Paddy label, which is now home to the Jameson Experience Visitor Centre and the Irish Whiskey Academy. The Jameson brand was acquired by the French drinks conglomerate Pernod Ricard in 1988, when it bought Irish Distillers. The old Jameson Distillery in Bow Street near Smithfield in Dublin now serves as a museum which offers tours and tastings. The distillery, which is historical in nature and no longer produces whiskey on site, went through a $12.6 million renovation that was concluded in March 2016, and is now a focal part of Ireland's strategy to raise the number of whiskey tourists, which stood at 600,000 in 2017.Bow Street also now has a fully functioning Maturation Warehouse within its walls since the 2016 renovation. It is here that Jameson 18 Bow Street is finished before being bottled at Cask Strength. In 2008, The Local, an Irish pub in Minneapolis, sold 671 cases of Jameson (22 bottles a day),making it the largest server of Jameson's in the world – a title it maintained for four consecutive years.

Classic Jameson Irish Whiskey Horse Racing advertisement from 1951 with a picture of the Epsom Derby winner Arctic Prince being led into the winners enclosure by his proud owner,Irish businessman and Founder of the Irish Hospital Sweepstakes ,Mr Joe McGrath. 50cm x 43cm. Dublin Joseph McGrath ( 12 August 1888 – 26 March 1966) was an Irish politician and businessman.He was a Sinn Féin and later a Cumann na nGaedheal Teachta Dála (TD) for various constituencies Dublin St James's (1918–21) Dublin North West (1921–23) and Mayo North (1923–27) and developed widespread business interests. McGrath was born in Dublin in 1888. By 1916 he was working with his brother George at Craig Gardiner & Co, a firm of accountants in Dawson Street, Dublin. He worked with Michael Collins, a part-time fellow clerk and the two struck up a friendship. In his spare time McGrath worked as secretary for the Volunteer Dependents' Fund. He soon joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood. He fought in Marrowbone Lane in the 1916 Easter Rising. McGrath was arrested after the rising, and jailed in Wormwood Scrubs and Brixton prisons in England. In the 1918 general election, he was elected as Sinn Féin TD for the Dublin St James's constituency, later sitting in the First Dáil.He was also a member of the Irish Republican Army, the guerrilla army of the Irish Republic, and successfully organised many bank robberies during the Irish war of Independence (1919–1921), where a small percentage of the proceeds was retained as a reward by him and his fellow-soldiers.During this time he was interred briefly at Ballykinlar Internment Camp. He escaped by dressing in army uniform and walking out of the gate with soldiers going on leave. He was eventually recaptured and spent time in jail in Belfast. In October 1921 McGrath travelled with the Irish Treaty delegation to London as one of Michael Collins' personal staff. When the Provisional Government of Ireland was set up in January 1922, McGrath was appointed as Minister for Labour. In the Irish Civil War of 1922–1923, he took the pro-treaty side and was made Director of Intelligence, replacing Liam Tobin. In a strongly worded letter, written in red ink, McGrath warned Collins not to take his last, ill-fated trip to Cork. He was later put in charge of the police Intelligence service of the new Irish Free State, the Criminal Investigation Department or CID. It was modelled on the London Metropolitan Police department of the same name, but was accused of the torture and killing of a number of republican (anti-treaty) prisoners during the civil war. It was disbanded at the war's end; the official reason given was that it was unnecessary for a police force in peacetime. McGrath went on to serve as Minister for Labour in the Second Dáil and the Provisional Government of Ireland. He also served in the 1st and 2nd Executive Councils holding the Industry and Commerce portfolio. In September 1922 McGrath used strikebreakers to oppose a strike by Trade Unionists in the Post Office service, despite having threatened to resign in the previous March of the same year when the government threatened to use British strikebreakers-four high profile IRA prisoners; Liam Mellows, Dick Barrett, Rory O'Connor, and Joe McKelvey. McGrath resigned from office in April 1924 because of dissatisfaction with the government's attitude to the Army Mutinyofficers and as he said himself, "government by a clique and by the officialdom of the old regime." By this he meant that former IRA fighters were being overlooked and that the Republican goals on all Ireland had been sidelined. McGrath and eight other TDs who had resigned from Cumann na nGaedheal then resigned their seats in the Dáil and formed a new political party, the National Party. However, the new party did not contest the subsequent by-elections for their old seats. Instead, Cumann na nGaedheal won seven of the seats and Sinn Féin won the other two. In 1927, McGrath took a libel case against the publishers of "The Real Ireland" by poet Cyril Bretherton, a book that claimed McGrath was responsible for the abduction and murder of Noel Lemass (the brother of Seán Lemass) in June 1923 during the Civil war, as well as a subsequent coverup. McGrath won the court case. During the 1930s, McGrath and Seán Lemass reconciled and regularly played poker together. Following his political career, he went on to become involved in the building trade. In 1925 he became labour adviser to Siemens-Schuckert, German contractors for the Ardnacrusha hydro-electric scheme near Limerick. McGrath founded the Irish Hospitals' Sweepstake in 1930, and the success of its sweepstakes made him an extremely wealthy man. He had other extensive and successful business interests always investing in Ireland and became Ireland's best-known racehorse owner and breeder, winning The Derby with Arctic Prince in 1951. McGrath died at his home, Cabinteely House, in Dublin on 26 March 1966. Cabinteely House, was donated to the state in 1986, and the land developed as a public park. Joe's son Paddy McGrath inherited many of his father's business interests, and also served as Fine Gael Senator from 1973 to 1977. John Jameson was originally a lawyer from Alloa in Scotland before he founded his eponymous distillery in Dublin in 1780.Prevoius to this he had made the wise move of marrying Margaret Haig (1753–1815) in 1768,one of the simple reasons being Margaret was the eldest daughter of John Haig, the famous whisky distiller in Scotland. John and Margaret had eight sons and eight daughters, a family of 16 children. Portraits of the couple by Sir Henry Raeburn are on display in the National Gallery of Ireland. John Jameson joined the Convivial Lodge No. 202, of the Dublin Freemasons on the 24th June 1774 and in 1780, Irish whiskey distillation began at Bow Street. In 1805, he was joined by his son John Jameson II who took over the family business that year and for the next 41 years, John Jameson II built up the business before handing over to his son John Jameson the 3rd in 1851. In 1901, the Company was formally incorporated as John Jameson and Son Ltd. Four of John Jameson’s sons followed his footsteps in distilling in Ireland, John Jameson II (1773 – 1851) at Bow Street, William and James Jameson at Marrowbone Lane in Dublin (where they partnered their Stein relations, calling their business Jameson and Stein, before settling on William Jameson & Co.). The fourth of Jameson's sons, Andrew, who had a small distillery at Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, was the grandfather of Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of wireless telegraphy. Marconi’s mother was Annie Jameson, Andrew’s daughter. John Jameson’s eldest son, Robert took over his father’s legal business in Alloa. The Jamesons became the most important distilling family in Ireland, despite rivalry between the Bow Street and Marrowbone Lane distilleries. By the turn of the 19th century, it was the second largest producer in Ireland and one of the largest in the world, producing 1,000,000 gallons annually. Dublin at the time was the centre of world whiskey production. It was the second most popular spirit in the world after rum and internationally Jameson had by 1805 become the world's number one whiskey. Today, Jameson is the world's third largest single-distillery whiskey. Historical events, for a time, set the company back. The temperance movement in Ireland had an enormous impact domestically but the two key events that affected Jameson were the Irish War of Independence and subsequent trade war with the British which denied Jameson the export markets of the Commonwealth, and shortly thereafter, the introduction of prohibition in the United States. While Scottish brands could easily slip across the Canada–US border, Jameson was excluded from its biggest market for many years. The introduction of column stills by the Scottish blenders in the mid-19th-century enabled increased production that the Irish, still making labour-intensive single pot still whiskey, could not compete with. There was a legal enquiry somewhere in 1908 to deal with the trade definition of whiskey. The Scottish producers won within some jurisdictions, and blends became recognised in the law of that jurisdiction as whiskey. The Irish in general, and Jameson in particular, continued with the traditional pot still production process for many years.In 1966 John Jameson merged with Cork Distillers and John Powers to form the Irish Distillers Group. In 1976, the Dublin whiskey distilleries of Jameson in Bow Street and in John's Lane were closed following the opening of a New Midleton Distillery by Irish Distillers outside Cork. The Midleton Distillery now produces much of the Irish whiskey sold in Ireland under the Jameson, Midleton, Powers, Redbreast, Spot and Paddy labels. The new facility adjoins the Old Midleton Distillery, the original home of the Paddy label, which is now home to the Jameson Experience Visitor Centre and the Irish Whiskey Academy. The Jameson brand was acquired by the French drinks conglomerate Pernod Ricard in 1988, when it bought Irish Distillers. The old Jameson Distillery in Bow Street near Smithfield in Dublin now serves as a museum which offers tours and tastings. The distillery, which is historical in nature and no longer produces whiskey on site, went through a $12.6 million renovation that was concluded in March 2016, and is now a focal part of Ireland's strategy to raise the number of whiskey tourists, which stood at 600,000 in 2017.Bow Street also now has a fully functioning Maturation Warehouse within its walls since the 2016 renovation. It is here that Jameson 18 Bow Street is finished before being bottled at Cask Strength. In 2008, The Local, an Irish pub in Minneapolis, sold 671 cases of Jameson (22 bottles a day),making it the largest server of Jameson's in the world – a title it maintained for four consecutive years. -

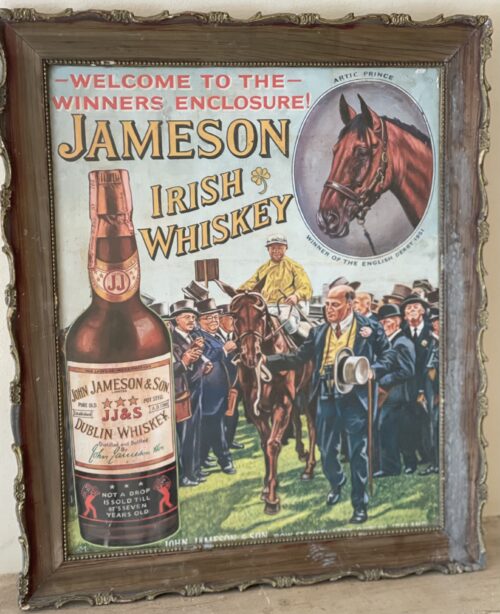

Boher Co Limerick 35cm x 48cm The 1994 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final was the 107th All-Ireland Final and the culmination of the 1994 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship. The match was held at Croke Park, Dublin, on 4 September 1994, between Offaly and Limerick. The Munster champions lost to their Leinster opponents on a score line of 3-16 to 2-13. The match is known as 'the five-minute final' due to the sensational comeback by Offaly who scored 2-5 to win the game in the last five minutes. With five minutes of normal time remaining, Limerick were leading by 2-13 to 1-11 and looked to be heading to their first title in 21 years when Offaly were awarded a free 20 metres from the goal. Limerick goalkeeper Joe Quaid later admitted that he was to blame for the resultant goal in that he didn't organise his defence well enough to stop a low-struck free from Johnny Dooley.[3] Quaid was erroneously blamed for Offaly's second goal after what was described as a quick and errant puck-out leading to Pat O'Connor putting Offaly a point ahead with a low shot to the net. Quaid later described the puck-out: "I didn’t rush back to the goals. I went back and picked up the ball, walked behind the goals like I normally would. Hegarty was out in the middle of the field on his own. I dropped the ball into his hand 70 yards out from goal. He caught the ball and in contact the ball squirted out of his hands." Because the television coverage was still showing a replay of the first goal, very few people got to see the build up to the second and when live transmission was resumed, the sliotar was still dropping towards Pat O'Connor leading people to assume that Quaid rushed his puck-out.Limerick went on to lose the game by 3-16 to 2-13.

Boher Co Limerick 35cm x 48cm The 1994 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final was the 107th All-Ireland Final and the culmination of the 1994 All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship. The match was held at Croke Park, Dublin, on 4 September 1994, between Offaly and Limerick. The Munster champions lost to their Leinster opponents on a score line of 3-16 to 2-13. The match is known as 'the five-minute final' due to the sensational comeback by Offaly who scored 2-5 to win the game in the last five minutes. With five minutes of normal time remaining, Limerick were leading by 2-13 to 1-11 and looked to be heading to their first title in 21 years when Offaly were awarded a free 20 metres from the goal. Limerick goalkeeper Joe Quaid later admitted that he was to blame for the resultant goal in that he didn't organise his defence well enough to stop a low-struck free from Johnny Dooley.[3] Quaid was erroneously blamed for Offaly's second goal after what was described as a quick and errant puck-out leading to Pat O'Connor putting Offaly a point ahead with a low shot to the net. Quaid later described the puck-out: "I didn’t rush back to the goals. I went back and picked up the ball, walked behind the goals like I normally would. Hegarty was out in the middle of the field on his own. I dropped the ball into his hand 70 yards out from goal. He caught the ball and in contact the ball squirted out of his hands." Because the television coverage was still showing a replay of the first goal, very few people got to see the build up to the second and when live transmission was resumed, the sliotar was still dropping towards Pat O'Connor leading people to assume that Quaid rushed his puck-out.Limerick went on to lose the game by 3-16 to 2-13. -

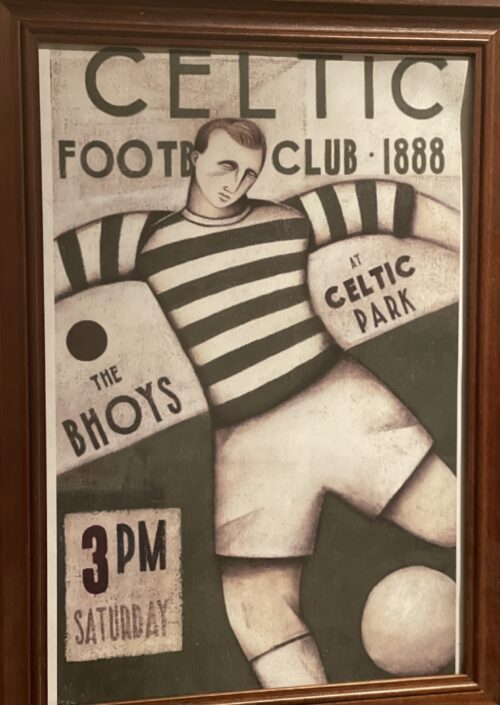

Framed Art Deco poster advertising Celtic FC Home games at Parkhead. 50cm x 40cm Co Donegal Celtic Football Club is a Scottish professional football club based in Glasgow, which plays in the Scottish Premiership. The club was founded in 1888 with the purpose of alleviating poverty in the immigrant Irish population in the East End of Glasgow. They played their first match in May 1888, a friendly match against Rangers which Celtic won 5–2. Celtic established themselves within Scottish football, winning six successive league titles during the first decade of the 20th century. The club enjoyed their greatest successes during the 1960s and 70s under Jock Stein, when they won nine consecutive league titles and the 1967 European Cup. Celtic have played in green and white throughout their history, adopting hoops in 1903, which have been used ever since. Celtic are one of only five clubs in the world to have won over 100 trophies in their history.The club has won the Scottish league championship 51 times, most recently in 2019–20, the Scottish Cup 40 times and the Scottish League Cup 19 times. The club's greatest season was 1966–67, when Celtic became the first British team to win the European Cup, also winning the Scottish league championship, the Scottish Cup, the League Cup and the Glasgow Cup. Celtic also reached the 1970 European Cup Final and the 2003 UEFA Cup Final, losing in both. Celtic have a long-standing fierce rivalry with Rangers, and the clubs are known as the Old Firm, seen by some as the world's biggest football derby. The club's fanbase was estimated in 2003 as being around nine million worldwide, and there are more than 160 Celtic supporters clubs in over 20 countries. An estimated 80,000 fans travelled to Seville for the 2003 UEFA Cup Final, and their "extraordinarily loyal and sporting behaviour" in spite of defeat earned the club Fair Play awards from FIFA and UEFA.

Framed Art Deco poster advertising Celtic FC Home games at Parkhead. 50cm x 40cm Co Donegal Celtic Football Club is a Scottish professional football club based in Glasgow, which plays in the Scottish Premiership. The club was founded in 1888 with the purpose of alleviating poverty in the immigrant Irish population in the East End of Glasgow. They played their first match in May 1888, a friendly match against Rangers which Celtic won 5–2. Celtic established themselves within Scottish football, winning six successive league titles during the first decade of the 20th century. The club enjoyed their greatest successes during the 1960s and 70s under Jock Stein, when they won nine consecutive league titles and the 1967 European Cup. Celtic have played in green and white throughout their history, adopting hoops in 1903, which have been used ever since. Celtic are one of only five clubs in the world to have won over 100 trophies in their history.The club has won the Scottish league championship 51 times, most recently in 2019–20, the Scottish Cup 40 times and the Scottish League Cup 19 times. The club's greatest season was 1966–67, when Celtic became the first British team to win the European Cup, also winning the Scottish league championship, the Scottish Cup, the League Cup and the Glasgow Cup. Celtic also reached the 1970 European Cup Final and the 2003 UEFA Cup Final, losing in both. Celtic have a long-standing fierce rivalry with Rangers, and the clubs are known as the Old Firm, seen by some as the world's biggest football derby. The club's fanbase was estimated in 2003 as being around nine million worldwide, and there are more than 160 Celtic supporters clubs in over 20 countries. An estimated 80,000 fans travelled to Seville for the 2003 UEFA Cup Final, and their "extraordinarily loyal and sporting behaviour" in spite of defeat earned the club Fair Play awards from FIFA and UEFA. -

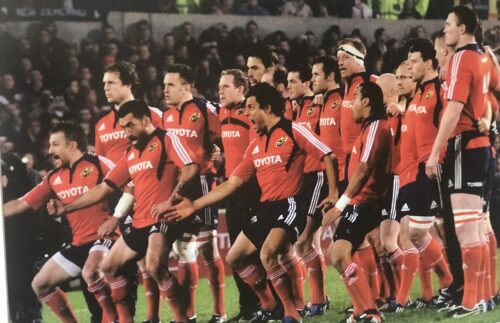

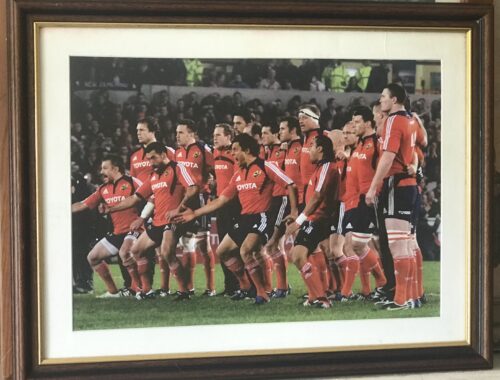

Fantastic framed photo of the famous Munster Haka performed by the New Zealand contingent wearing red- Doug Howlett,Lifemi Mafi,Jeremy Manning & Rua Tipoki. Limerick 45cm x60cm WHAT DO YOU remember most about this game? 12 years have passed now but what sticks out is how low-key the build-up was until the moment of the famous response to the haka from Munster’s New Zealand contingent. Low-key in the sense that not a whole lot was expected from the game itself. The occasion was always going to be a bit of crack with all the players from the epic day in ’78 being wheeled out to give interviews about the time they slayed the giant from the land of the long white cloud. But after all the clips and interviews with Seamus Dennison and Tony Ward were over, was anyone seriously expecting a proper contest from the game? Sure, it was an All Blacks ‘B’ side (although at the time, their second-string consisted of Cory Jane, Liam Messam, Kieran Read and Hosea Gear) but it was also a weakened Munster team, with Denis Leamy the only first choice forward available due to international commitments. The state of the two line-ups meant that two of rugby’s most well-worn clichés were put head-to-head: ‘There is no such thing as an All Blacks B team’ vs ‘you can never count out Munster’. Given what followed, you would probably say it was a push. The first sense that the game might channel the spirit of ’78 rather than just pay tribute to it was obviously during the haka. This would have been the perfect sporting moment if you could have erased Jeremy Manning’s Village People moustache out of there. The Thomond Park crowd rarely needs any encouragement but the ground was heaving after that introduction. Then the game started and the untested members of the Munster pack were the most tigerish. James Coughlan was basically a 28-year-old club player at the time but his ferocious display of carrying earned him a proper professional career. Donnacha Ryan exploded out of POC and DOC’s shadow with an commanding performance and Munster were clinical early on. It helped that out-half Paul Warwick was in the form of his life. These monster drop goals were a regular sight during that 2008-09 season. The All Blacks hit back with a try from Stephen ‘Beaver’ Donald but right on half time, Munster took a six point lead after this Barry Murphy try. This was one of those classic moments during an upset when you turn to a mate, nod vigorously and say ‘It’s on now' Half time came a moment later and with it, this nice gesture from Cory Jane. For most Irish fans, this was the first time they had seen Jane in action and this moment, coupled with his strong attacking performance marked him as one of the good guys. I can’t speak for anyone else, but the only thing I remember about the second half is Joe Rokocoko’s try – probably because Munster didn’t score in the second 40. Munster held out for 76 minutes until Rokocoko got the ball directly against his old teammate Doug Howlett. Should Howlett have made the tackle? It is hard to stop Smokin’ Joe when he plants that foot. And that was it. There was no heroic win. Unknown players like prop Timmy Ryan didn’t get to join the heroes of ’78 as regulars on the after-dinner speech circuit. What made this such a memorable occasion was how unexpected it was. It was played on a Tuesday, sandwiched between two other November Tests and although the pageantry was always going to be good fun, the fact that it exploded into life in the way it did makes it one of the most exciting games in the history of Irish rugby. It’s been six years now, but the memory of ‘It’s on’ is one that will never go away. Munster: Howlett; B Murphy, Tipoki, Mafi, Dowling; Warwick, Stringer; Pucciariello, Sheahan, Ryan; M O’Driscoll (capt), Ryan; Coughlan, Ronan, Leamy. Replacements: Buckley for Ryan 40, Fogarty for Sheahan 63, Holland for Leamy 24, Manning for Tipoki 52. Not used: Melbourne, O’Sullivan, Prendergast New Zealand: Jane; H Gear, Tuitavake, Toeava, Rokocoko; Donald, Weepu (capt); Mackintosh, Flynn, Franks, Filipo, Eaton, Thomson, Waldrom, Messam. Replacements: Elliott for Flynn 65, Afoa for Franks 70, B Thorn for Filipo 71, Read for Thomson 60, Mathewson for Weepu 63, Muliaina for Tuitavake 71. Not used: Kahui,