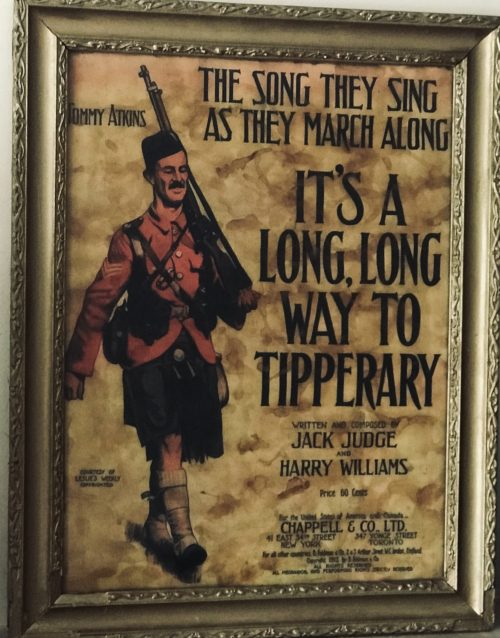

Superb vintage poster advertising the famous WW1 era music hall song of 'Its a long long way to Tipperary".

60cm x 45cm London United Kingdom

Long Way to Tipperary" (or "

It's a Long, Long Way to Tipperary") is a British

music hall song first performed in 1912 by

Jack Judge, and written by Judge and Harry Williams though authorship of the song has long been disputed.

It was recorded in 1914 by Irish tenor

John McCormack. It became popular as a

marching song among soldiers in the

First World War and is remembered as

a song of that war. Welcoming signs in the referenced county of

Tipperary, Ireland, humorously declare, "You've come a long long way..." in reference to the song.

Authorship

Jack Judge's parents were Irish, and his grandparents came from

Tipperary. Judge met Harry Williams (Henry James Williams, 23 September 1873 – 21 February 1924) in

Oldbury, Worcestershire at the Malt Shovel public house, where Williams's brother Ben was the licensee. Williams was severely disabled, having fallen down cellar steps as a child and badly broken both legs. He had developed a talent for writing verse and songs, and played the piano and

mandolin, often in public. Judge and Williams began a long-term writing partnership that resulted in 32 music hall songs published by

Bert Feldman. Many of the songs were composed by Williams and Judge at Williams's home, The Plough Inn (later renamed The Tipperary Inn), in

Balsall Common. Because Judge could not read or write music, Williams taught them to Judge by ear.

Judge was a popular semi-professional performer in music halls. In January 1912, he was performing at the Grand Theatre in

Stalybridge, and accepted a 5-

shilling bet that he could compose and sing a new song by the next night. The following evening, 31 January, Judge performed "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" for the first time, and it immediately became a great success. The song was originally written and performed as a sentimental ballad, to be enjoyed by Irish expatriates living in London.

Judge sold the rights to the song to Bert Feldman in London, who agreed to publish it and other songs written by Judge with Williams.

Feldman published the song as "It's a Long, Long Way to Tipperary" in October 1912, and promoted it as a

march.

Dispute

Feldman paid royalties to both Judge and Williams, but after Williams' death in 1924, Judge claimed sole credit for writing the song,

saying that he had agreed to Williams being co-credited as recompense for a debt that Judge owed. However, Williams' family showed that the tune and most of the lyrics to the song already existed in the form of a manuscript, "It's A Long Way to Connemara", co-written by Williams and Judge back in 1909, and Judge had used this, just changing some words, including changing "Connemara" to "Tipperary"

Judge said: "I was the sole composer of 'Tipperary', and all other songs published in our names jointly. They were all 95% my work, as Mr Williams made only slight alterations to the work he wrote down from my singing the compositions. He would write it down on music-lined paper and play it back, then I'd work on the music a little more ... I have sworn affidavits in my possession by Bert Feldman, the late Harry Williams and myself confirming that I am the composer ...". In a 1933 interview, he added: "The words and music of the song were written in the Newmarket Tavern, Corporation Street, Stalybridge on 31st January 1912, during my engagement at the Grand Theatre after a bet had been made that a song could not be written and sung the next evening ... Harry was very good to me and used to assist me financially, and I made a promise to him that if I ever wrote a song and published it, I would put his name on the copies and share the proceeds with him. Not only did I generously fulfil that promise, but I placed his name with mine on many more of my own published contributions. During Mr Williams' lifetime (as far as I know) he never claimed to be the writer of the song ...".

Williams's family campaigned in 2012 to have Harry Williams officially re-credited with the song, and shared their archives with the

Imperial War Museums. The family estate still receives royalties from the song.

Other claims

In 1917, Alice Smyth Burton Jay sued song publishers

Chappell & Co. for $100,000, alleging she wrote the tune in 1908 for a song played at the

Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition promoting the Washington apple industry. The chorus began "I'm on my way to

Yakima".

The court appointed

Victor Herbert to act as expert advisor

and dismissed the suit in 1920, since the authors of "Tipperary" had never been to

Seattle and Victor Herbert testified the two songs were not similar enough to suggest plagiarism.

Content

The song was originally written as a lament from an Irish worker in London, missing his homeland, before it became a popular soldiers' marching song. One of the most popular hits of the time, the song is atypical in that it is not a warlike song that incites the soldiers to glorious deeds. Popular songs in previous wars (such as the

Boer Wars) frequently did this. In the First World War, however, the most popular songs, like this one and "

Keep the Home Fires Burning", concentrated on the longing for home.

Reception

Feldman persuaded

Florrie Forde to perform the song in 1913, but she disliked it and dropped it from her act.

However, it became widely known. During the

First World War,

Daily Mailcorrespondent George Curnock saw the Irish regiment the

Connaught Rangers singing this song as they marched through

Boulogne on 13 August 1914, and reported it on 18 August 1914. The song was quickly picked up by other units of the

British Army. In November 1914, it was recorded by Irish tenor

John McCormack, which helped its worldwide popularity.

Other popular versions in the USA in 1915 were by the

American Quartet,

Prince's Orchestra, and Albert Farrington.

The popularity of the song among soldiers, despite (or because of) its irreverent and non-military theme, was noted at the time, and was contrasted with the military and patriotic songs favoured by enemy troops. Commentators considered that the song's appeal revealed characteristically British qualities of being cheerful in the face of hardship.

The Times suggested that "'Tipperary' may be less dignified, but it, and whatever else our soldiers may choose to sing will be dignified by their bravery, their gay patience, and their long suffering kindness... We would rather have their deeds than all the German songs in the world."

Later performances

Early recording star

Billy Murray, with the American Quartet, sang "It's A Long Way To Tipperary" as a straightforward march, complete with brass, drums and cymbals, with a quick bar of "

Rule, Britannia!" thrown into the instrumental interlude between the first and second verse-chorus combination.

The song was featured as one of the songs in the 1951 film

On Moonlight Bay, the 1960s stage musical and film

Oh! What a Lovely War and the 1970 musical

Darling Lili, sung by

Julie Andrews. It was also sung by the prisoners of war in

Jean Renoir's film

La Grande Illusion (1937) and as background music in

The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming (1966). It is also the second part (the other two being

Hanging on the Old Barbed Wire and

Mademoiselle from Armentières) of the regimental march of

Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry.

Mystery Science Theater 3000 used it twice, sung by

Crow T. Robot in

Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie (1996), then sung again for the final television episode. It is also sung by British soldiers in the film

The Travelling Players (1975) directed by

Theo Angelopoulos, and by

Czechoslovak soldiers in the movie

Černí baroni (1992).

The song is often cited when documentary footage of the First World War is presented. One example of its use is in the annual television special

It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown (1966).

Snoopy—who fancies himself as a First World War flying ace—dances to a medley of First World War-era songs played by

Schroeder. This song is included, and at that point Snoopy falls into a left-right-left marching pace. Schroeder also played this song in

Snoopy, Come Home (1972) at Snoopy's send-off party. Also, Snoopy was seen singing the song out loud in a series of strips about his going to the

1968 Winter Olympics. In another strip, Snoopy is walking so long a distance to Tipperary that he lies down exhausted and notes, "They're right, it is a long way to Tipperary." On a different occasion, Snoopy walks along and begins to sing the song, only to meet a sign that reads, "Tipperary: One Block." In a Sunday strip wherein Snoopy, in his World War I fantasy state, walks into

Marcie's home, thinking it a French café, and falls asleep after drinking all her root beer, she rousts him awake by loudly singing the song.

It is also featured in

For Me and My Gal (1942) starring

Judy Garland and

Gene Kelly and

Gallipoli (1981) starring

Mel Gibson.

The cast of

The Mary Tyler Moore Show march off screen singing the song at the conclusion of the series’ final episode, after news anchor

Ted Baxter (played by

Ted Knight) had inexplicably recited some of the lyrics on that evening's news broadcast.

It was sung by the crew of

U-96 in

Wolfgang Petersen's 1981 film

Das Boot (that particular arrangement was performed by the

Red Army Choir). Morale is boosted in the submarine when the German crew sings the song as they begin patrolling in the North Atlantic Ocean. The crew sings it a second time as they cruise toward home port after near disaster.

When the

hellship SS Lisbon Maru was sinking, the Royal Artillery POWS trapped in the vessel are reported to have sung this song.

Survivors of the sinking of

HMS Tipperary in the

Battle of Jutland (1916) were identified by their rescuers on

HMS Sparrowhawk because they were singing "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" in their lifeboat.

In

Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie (1996), based on the popular cable series

Mystery Science Theater 3000, robot character Crow T. Robot sings a version of the song while wearing a World War I British Army helmet, and declaring "We must confound Gerry (the Germans) at every turn!"

Lyrics

Up to mighty London

Came an Irishman one day.

As the streets are paved with gold

Sure, everyone was gay,

Singing songs of Piccadilly,

Strand and Leicester Square,

Till Paddy got excited,

Then he shouted to them there:

Chorus

It's a long way to Tipperary,

It's a long way to go.

It's a long way to Tipperary,

To the sweetest girl I know!

Goodbye, Piccadilly,

Farewell, Leicester Square!

It's a long long way to Tipperary,

But my heart's right there.

Paddy wrote a letter

To his Irish Molly-O,

Saying, "Should you not receive it,

Write and let me know!"

"If I make mistakes in spelling,

Molly, dear," said he,

"Remember, it's the pen that's bad,

Don't lay the blame on me!"

Chorus

Molly wrote a neat reply

To Irish Paddy-O,

Saying "Mike Maloney

Wants to marry me, and so

Leave the Strand and Piccadilly

Or you'll be to blame,

For love has fairly drove me silly:

Hoping you're the same!"

Chorus

An alternative

bawdy concluding chorus:

That's the wrong way to tickle Mary,

That's the wrong way to kiss.

Don't you know that over here, lad

They like it best like this.

Hoo-ray pour les français,

Farewell Angleterre.

We didn't know how to tickle Mary,

But we learnt how over there.