-

26cm x 33cm Fantastic shot of the most westerly GAA pitch in Ireland and prob in Western Europe-the pitch on Care Island where the resourceful locals have mangaged to produce a decent playing surface on the only flat patch of land on the island ! Inishturk (Inis Toirc in Irish, meaning Wild Boar Island) is an inhabited island of County Mayo, in Ireland.

26cm x 33cm Fantastic shot of the most westerly GAA pitch in Ireland and prob in Western Europe-the pitch on Care Island where the resourceful locals have mangaged to produce a decent playing surface on the only flat patch of land on the island ! Inishturk (Inis Toirc in Irish, meaning Wild Boar Island) is an inhabited island of County Mayo, in Ireland.Geography

The island lies about 15 km (9 mi) off the coast; its highest point reaches 189.3 m (621.1 ft) above sea level. Between Inisturk and Clare Island lies Caher Island. It has a permanent population of 58 people.There are two main settlements, both on the more sheltered eastern end of the island, Ballyheer and Garranty. Bellavaun and Craggy are abandoned settlements. The British built a Martello tower on the western coast during the Napoleonic Wars. Inisturk has the highest per capita donation rate towards the RNLI in the whole of Ireland.History

Inishturk has been inhabited on and off since 4,000 BCE and has been inhabited permanently since at least 1700. Some of the more recent inhabitants are descended from evacuees from Inishark to the southwest. The social club Mountain Common is situated on the hill that separates the two settlements.Recent history

In 1993 Inishturk Community centre was opened, this community centre doubles as a library and a pub. In June 2014 the ESB commissioned three new Broadcrown BCP 110-50 100kVA diesel generators to supply electricity to the island The ESB have operated a diesel power station on the island since the 1980s Inishturk gained international attention in 2016 after a number of websites claimed that the island would welcome any American "refugees" fleeing a potential Donald Trump presidency.These claims were used as one example of the type of "fake news" that arose during the 2016 US presidential election campaign. As of November 2016, no changes to inward migration have been reported. The island is home to a primary school on the island which in 2011 had only 3 pupils, this believed to be the smallest primary school in IrelandDemographics

The table below reports data on Inisturk's population taken from Discover the Islands of Ireland (Alex Ritsema, Collins Press, 1999) and the Censusof Ireland.Historical population Year Pop. ±% 1841 577 — 1851 174 −69.8% 1861 110 −36.8% 1871 112 +1.8% 1881 116 +3.6% 1891 135 +16.4% 1901 135 +0.0% 1911 132 −2.2% 1926 101 −23.5% Year Pop. ±% 1936 107 +5.9% 1946 125 +16.8% 1951 123 −1.6% 1956 110 −10.6% 1961 108 −1.8% 1966 92 −14.8% 1971 83 −9.8% 1979 85 +2.4% 1981 76 −10.6% Year Pop. ±% 1986 90 +18.4% 1991 78 −13.3% 1996 83 +6.4% 2002 72 −13.3% 2006 58 −19.4% 2011 53 −8.6% 2016 51 −3.8% Source: Central Statistics Office. "CNA17: Population by Off Shore Island, Sex and Year". CSO.ie. Retrieved October 12, 2016. Transport[edit]

Prior to 1997 there was no scheduled ferry service and people traveled to and from the islands using local fishing boats. Since then a ferry service operates from Roonagh Quay, Louisburgh, County Mayo.[13] The pier was constructed during the 1980s by the Irish government, around this time the roads on the island were paved.[14] -

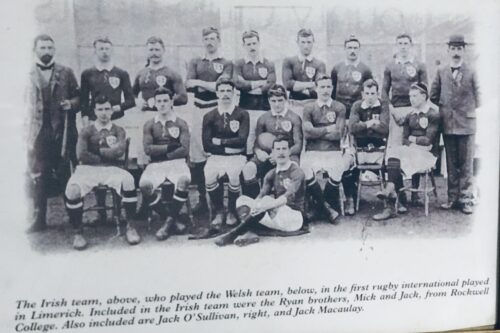

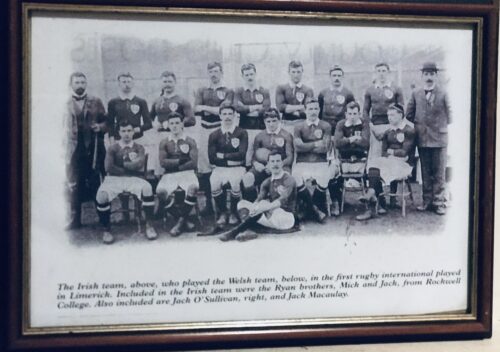

Team photograph of the Irish Rugby Team that played Wales in the first ever Rugby International ever held in Limerick in the County Cricket Grounds (now the Limerick Lawn Tennis Club) Ennis Road on the 19th March 1898. 42cm x 30cm Parnell St Limerick City

Team photograph of the Irish Rugby Team that played Wales in the first ever Rugby International ever held in Limerick in the County Cricket Grounds (now the Limerick Lawn Tennis Club) Ennis Road on the 19th March 1898. 42cm x 30cm Parnell St Limerick City

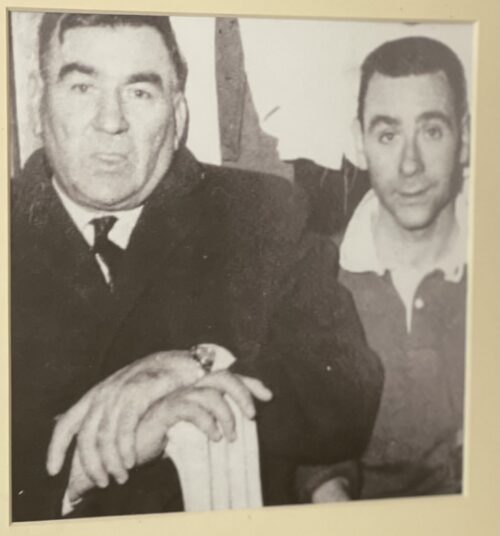

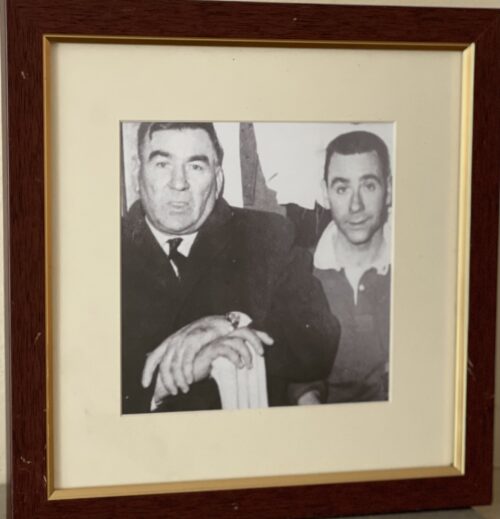

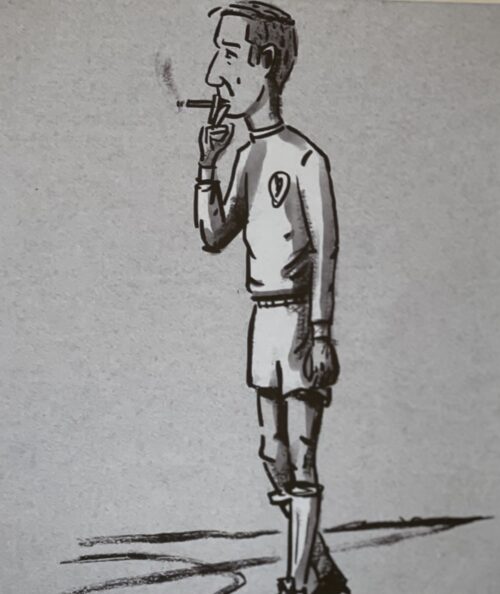

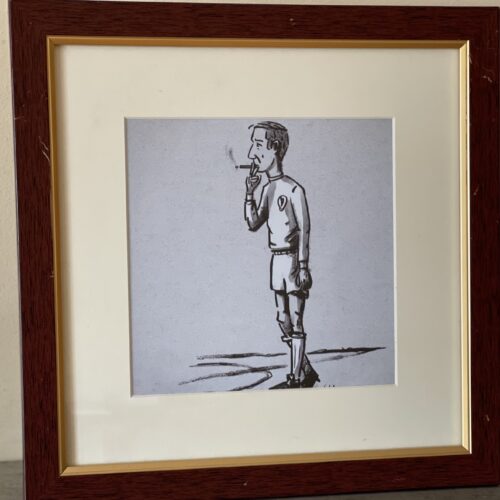

30cm x 30cm John Charlton OBE (8 May 1935 – 10 July 2020) was an English footballer and manager who played as a defender. He was part of the England team that won the 1966 World Cup and managed the Republic of Ireland national team from 1986 to 1996 achieving two World Cup and one European Championship appearances. He spent his entire club career with Leeds United from 1950 to 1973, helping the club to the Second Division title (1963–64), First Division title (1968–69), FA Cup (1972), League Cup (1968), Charity Shield (1969), Inter-Cities Fairs Cup (1968 and 1971), as well as one other promotion from the Second Division (1955–56) and five second-place finishes in the First Division, two FA Cup final defeats and one Inter-Cities Fairs Cup final defeat. His 629 league and 762 total competitive appearances are club records. He was the elder brother of former Manchester United forward Bobby Charlton, who was also a teammate in England's World Cup final victory. In 2006, Leeds United supporters voted Charlton into the club's greatest XI.[4] Called up to the England team days before his 30th birthday, Charlton went on to score six goals in 35 international games and to appear in two World Cups and one European Championship. He played in the World Cup final victory over West Germany in 1966, and also helped England to finish third in Euro 1968 and to win four British Home Championship tournaments. He was named FWA Footballer of the Year in 1967. After retiring as a player he worked as a manager, and led Middlesbrough to the Second Division title in 1973–74, winning the Manager of the Year award in his first season as a manager. He kept Boro as a stable top-flight club before he resigned in April 1977. He took charge of Sheffield Wednesday in October 1977, and led the club to promotion out of the Third Division in 1979–80. He left the Owls in May 1983, and went on to serve Middlesbrough as caretaker-manager at the end of the 1983–84 season. He worked as Newcastle United manager for the 1984–85 season. He took charge of the Republic of Ireland national team in February 1986, and led them to their first World Cup in 1990, where they reached the quarter-finals. He also led the nation to successful qualification to Euro 1988 and the 1994 World Cup. He resigned in January 1996 and went into retirement. He was married to Pat Kemp and they had three children.

Ireland manager Jack Charlton and assistant Maurice Setters after the loss to Italy in the quarter-finals of the 1990 World Cup

30cm x 30cmJohn Charlton OBE (8 May 1935 – 10 July 2020) was an English footballer and manager who played as a defender. He was part of the England team that won the 1966 World Cup and managed the Republic of Ireland national team from 1986 to 1996 achieving two World Cup and one European Championship appearances. He spent his entire club career with Leeds United from 1950 to 1973, helping the club to the Second Division title (1963–64), First Division title (1968–69), FA Cup (1972), League Cup (1968), Charity Shield (1969), Inter-Cities Fairs Cup (1968 and 1971), as well as one other promotion from the Second Division (1955–56) and five second-place finishes in the First Division, two FA Cup final defeats and one Inter-Cities Fairs Cup final defeat. His 629 league and 762 total competitive appearances are club records. He was the elder brother of former Manchester United forward Bobby Charlton, who was also a teammate in England's World Cup final victory. In 2006, Leeds United supporters voted Charlton into the club's greatest XI.[4] Called up to the England team days before his 30th birthday, Charlton went on to score six goals in 35 international games and to appear in two World Cups and one European Championship. He played in the World Cup final victory over West Germany in 1966, and also helped England to finish third in Euro 1968 and to win four British Home Championship tournaments. He was named FWA Footballer of the Year in 1967. After retiring as a player he worked as a manager, and led Middlesbrough to the Second Division title in 1973–74, winning the Manager of the Year award in his first season as a manager. He kept Boro as a stable top-flight club before he resigned in April 1977. He took charge of Sheffield Wednesday in October 1977, and led the club to promotion out of the Third Division in 1979–80. He left the Owls in May 1983, and went on to serve Middlesbrough as caretaker-manager at the end of the 1983–84 season. He worked as Newcastle United manager for the 1984–85 season. He took charge of the Republic of Ireland national team in February 1986, and led them to their first World Cup in 1990, where they reached the quarter-finals. He also led the nation to successful qualification to Euro 1988 and the 1994 World Cup. He resigned in January 1996 and went into retirement. He was married to Pat Kemp and they had three children.

Ireland manager Jack Charlton and assistant Maurice Setters after the loss to Italy in the quarter-finals of the 1990 World Cup

16cm x 25cm. Dublin

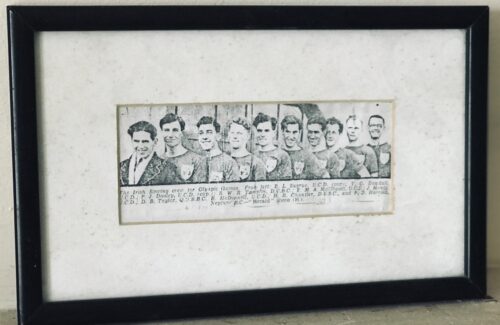

16cm x 25cm. DublinHOLDING OF THE THIN GREEN LINE – UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN BOAT CLUB & THE 1948 OLYMPIC GAMES

BY MORGAN MCELLIGOTT

“Telegram for you, Professor.” The year was 1948 in Mooney’s of the Strand. Jim read “Flight delayed, cannot make Mooney’s, see you at Henley- on – Thames signed Holly.” Apparently the barman was transferred from the Dublin premises near Independent House to London and recognised his erstwhile customer, Jim Meenan. “Holly” was a sobriquet for J.J.E. Holloway, representative of the Leinster branch of the Irish Amateur Rowing Union (I.A.R.U.) and to the Federation Internationale des Societes d’Aviron (F.I.S.A.). The former was secretary and later President of the union. Both were officers of Old Collegians Boat Club (O.C.B.C.) and members of the emergency committee to deal with the Irish Olympic eight-oar crew entry and were hugely involved with the development of U.C.D. rowing. The Club founded in 1918, assumed significance in the thirties and peaked in 1939 by winning the intervarsity Wylie Cup and the Irish Senior and Junior Rowing Championships, coached by Holly and captained by Dermot Pierce, brother of Denis Sugrue.1947-1948

After some lean years, the College aimed at revivification under the author’s captaincy, by intensive training twice daily in 1947, repeating the above wins and making a significant inaugural appearance at the Royal Henley Regatta by beating Reading University and Kings College London in the initial rounds in the Thames Cup before elimination in the semi-final by the eventual winners, Kent School U.S.A. It was easy to predict the outcome of the 1948 season which, captained by Paddy Dooley, repeated the above Irish competitive season, finishing by victory in the final of the Irish Senior Eights Championship over Belfast Commercial Boat Club, at present Belfast Rowing Club, on the river Lagan.

CREW SELECTED

The I.A.R.U. had ruled previously that the winning eight would be nominated as an All- Ireland entry to the Olympic Games and the relevant sub-committee met immediately after the race on the 10th July 1948 and U.C.D. were invited to form the Olympic Crew. Dominant advice was given and accepted fully from Ray Hickey, who rowed in the successful Senior Championship eight in 1940 and coached both 1947 and 1948 crews. Initial practice was on the 12th and the crew was finally selected on the 16th July as follows:-Bow

T.G. Dowdall

UCD

2E.M.A McElligott

UCD

3J. Hanly

UCD

4D.D.B. Taylor

Queen’s

5B. McDonnell

UCD

6P.D.R. Harold

Neptune

7R.W.R Tamplin

Trinity

StrokeP.O. Dooley

UCD

CoxD.L. Sugrue

UCD

Coaches

R.G. Hickey

UCD

M. Horan

Trinity

Manager

D.S.F. O’Leary

UCD

Substitutes

H.R. Chantler

Trinity

W. Stevens

Neptune

EIRE/IRELAND-26/32

So far it seemed simple, but now it was the Eire/Ireland question; briefly, “Eire” meant pick your athletes from twenty-six counties, whereas “Ireland”‘ meant thirty-two counties. Dan Taylor, Captain of the Q.U.B.C. was included and the I.A.R.U. was not yet a member of the F.I.S.A. Some seventeen days of training followed on both Liffey and Thames. Long mileage was the hallmark of the college crews in the previous two seasons and included an indelibly remembered row from Islandbridge to Poolbeg Lighthouse on a calm day, it was subsequently learned that the U.S.A. and Norway, gold and bronze medal winners, crewed for two years and nine months respectively.BORDERLINE CONSEQUENCES

But more important matters were imminent in Henley-on-Thames Town Hall, such as, “Can we row Danny from Queens, Belfast? ” John Pius Boland, of Boland’s Bread and a law graduate of Balliol College Oxford, was a commissioner under the Irish Universities Act and named the new establishment the National University of Ireland. Earlier, in 1896, after winning two gold medals for tennis in the first Olympic Games of the modern era, he caused some upset when he demanded an Irish flag. Subsequent to the establishment of the twenty-six country Irish Free State, the question of Olympic entry from a thirty-two county Ireland was debated and re-affirmed at four international Olympic committee meetings ranging from Paris in 1924 to Berlin in 1930. In 1932, Bob Tisdall, 400 meters hurdle and Pat O’Callaghan, hammer, won gold medals; the thirty-two county status was thought to be ensured in spite of persistent objections by British, representatives, which were constantly over-ruled until 1934. In context, Sean Lavan of U.C.D. achieved first and second places in various heats of 200 and 400 meters in 1924 and 1928.ORATIO RECTA 1948 dialectic included: –

BOADICEA: Conqueror of Italians: “Eire is on your stamps and on your Department of External Affairs note paper.” MACHA: war Goddess of Ulster: “Yes, and you have Helvetia on your stamps and Switzerland on your note paper.” BOADICEA: “Eirelevant! And note the spelling, if you’ve graduated from Ogham. Your swimmers are already barred because of the inclusion of Northern Ireland competitors.” MACHA: “A jarvey’s arrogance, why, you have four competitors, born in southern Ireland including Chris Barton from Kildare, who stroked the British eight, winning a silver medal. Being rather proud of our athletic exports, we never raised the issue.” BOADICEA: “Verdant remarks from a verdant person, and how about Danny Boy from Queen’s University Boat Club.” MACHA: “Well, he is entitled to British and Irish passports and that reminds me of your performance of an Irish melody, the Londonderry Air which concerns my fief. BOADICEA: “Your Kevin Myers states you cannot be “Ireland” without a referendum.” MACHA: “Anachronisms are unacceptable and on your next raid on Londinium ask the king’s equerry why he introduced my friends as “Ireland” at the Buckingham Palace tea-party”.

FAULTY TOWERS

The twin towers of Wembley stadium came into view, we were going on parade with increased confidence in our entry, while the swimmers returned to Eire/Ireland. As we took our place, it appeared that the parade sign-board was Eire rather than Ireland. A rather polemic discussion ensued between the assistant Chief Marshal and Comdt. J.F. Chisholm, the Irish Chef de Mission; the latter pointed out that our entry was submitted and accepted as “Ireland” as the English language was mandatory in context e.g. Espana marched as Spain. The Marshal’s convincing riposte was that he always wrote “Eire” when writing to his Irish brother-in-law and that P. agus T. delivered accurately; this was followed by an awesome threat to trap us in the tunnel.

CORK’S CREWMANSHIP

The ebullient Donal S.F. O Leary, who rowed in the successful 1947 Wylie Cup senior eight, with Alphie Walshe, and, at present, our team manager assessed instantly the situation and when we were directed to march in line after Iraq, declared forcibly that there were thousands of Irish, or was it Eirish, people in the stands ready to cheer their team and wouldn’t it be an huge disappointment if we failed to march, on a matter of neology.

ON STREAM

In a temperature 90 F, with 58 nations, we marched as “Eire,” saluted King GeorgeVl, were cheered loudly by our own and by countries like India which recently gained independence, as we worried about losing a day’s practice on the water. The words of the visionary Pierre Baron de Coubertin, who revived the Olympic Games in 1896 after a lapse of some 1600 years, dominated the stadium:

THE IMPORTANT THING IN THE OLYMPIC GAMES IS NOT WINNING BUT TAKING PART. THE ESSENTIAL THING IN LIFE IS NOT CONQUERING BUT FIGHTING WELL

The Olympic torch, carried through a peaceful Europe, arrived and the Olympic flame was lit by Cambridge athlete, John Mark. Donald Finlay, former Olympic hurdler swore the oath. The King proclaimed the games open, Sir Malcolm Sergent, of the Albert Hall promenade concerts, conducted the orchestra with guards massed bands and choir in a stirring performance of the Londonderry Air; thousands of pigeons were released to carry messages of peace to countries of the world.UP STREAMBut upstream to Henley, the thirty-two county body I.A.R.U., represented by its President M.V. Rowan of Neptune R.C. and J.J.E. Holloway O.C.B.C., was elected unanimously to F.I.S.A. and was therefore the first athletic unit recognised as an all Ireland body at the XIV Olympiad. A laudable photo-finish as competition started on the morrow and it’s worth mentioning that, in contrast to current debatable practice, Irish rowing officials disclaimed all expenses.

LADIES LAST AND FIRST

A liberal proposal by eastern European countries “on the organisation of feminine championships received scant attention”. An Antipodean delegate stated that in his opinion: “Rowing, as a sport had sufficient complications without adding the feminine element thereto”. In a recent season Antipodean values, not delegates, prevailed in U.C.D. Ladies Boat Club captained by Oonagh Clarke; wins of their Senior Eight included Ghent International Regatta and Henley Regatta, beating Temple University U.S.A. in the final – a glorious season for the “feminine element”.THIN GREEN LINE

During all this induction, practice continued on the water. Most of the crew thought pragmatically that as long as we rowed all else was irrelevant. Heart or head, to be conservative at twenty is to have no heart, to be socialist at forty is to have no head. Initially some of our training was alongside the British crew, whom we could beat transiently off the starting stake-boat; the objection of other crews ended this liaison. Our exercise times over parts of the course proved favourably and superior to some of our competitors but on the day we were beaten in our heat by Canada and Portugal and the repechage by Norway. To quote Michael Johnston in his totally comprehensive book on Senior Championship rowing, entitled “The Big Pot”:- “They lost their races but held the Thin Green Line and brought Ireland into the world of real international rowing for the first time. “MEMORIA

Joe Hanly and Barry McDonnell were both heavy weights on the 1947 and 1948 championship crews, and subsequently Presidents of O.C.B.C. Joe was also Vice-Captain of U.C.D.B.C. in 1947. Barry died in 1976 and Joe in 1996. The sympathy of all U.C.D. Oarsmen was extended to their wives, Helen who was Inaugural President of U.C.D.B.C. Ladies, and Jane, respectively. In 1997 Joe was honoured posthumously in the presence of Jane and Dr. Art Cosgrove, President U.C.D., by naming a new fine VIII boat, “Joe Hanly” in the presence of Barry Doyle, President U.C.D.B.C. RESURRECTI SUMUSIn 1998 the 1948 Olympic crew were honoured in the presence of some 170 crews competing in the Irish National Rowing Championships. Inscribed trophies and pennants were presented by Tom Fennessy, President of the I.A.R.U. and Michael Johnston, in his citation, stressed how the crew ensured thirty-two county representation by holding the Thin Green Line.

Similarly, twenty-five contestants, out of a total ninety-one who competed in 1948, attended a reception hosted by the Irish Olympic Council. Trophies were presented and citations declared by Patrick Hickey. President of the Council. Speeches included that of Dave Guiney, National Irish Shop-Putting Champion, who spoke for the recipients, and Dr. Kevin O’Flanagan who received a special presentation for his medical services to the Games. During his student days at U.C.D. in the 1940’s, O’Flanagan developed a career which included winning National Championships for Sprinting, playing International Soccer and Rugby for Ireland.

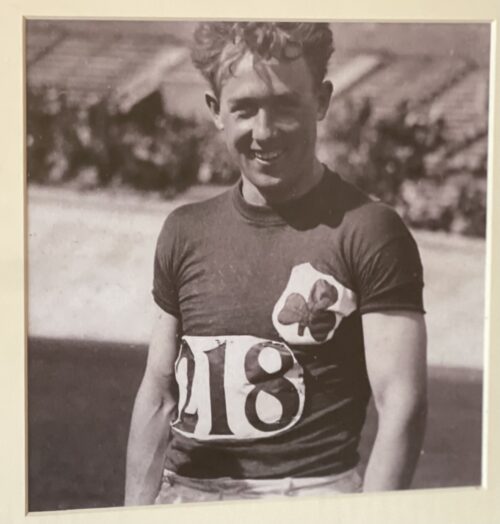

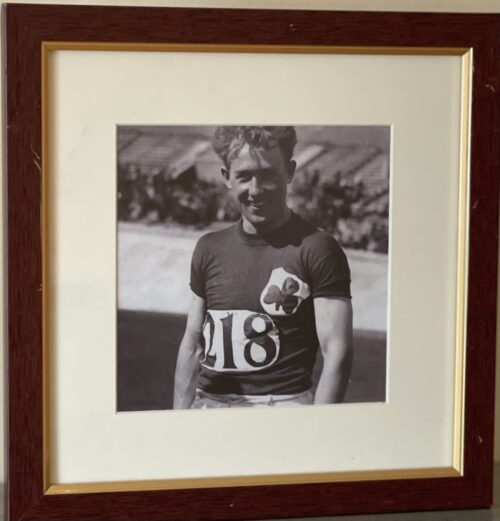

30cm x 30cm Patrick "Pat" O'Callaghan (28 January 1906 – 1 December 1991) was an Irish athlete and Olympic gold medallist. He was the first athlete from Ireland to win an Olympic medal under the Irish flag rather than the British. In sport he then became regarded as one of Ireland's greatest-ever athletes.

30cm x 30cm Patrick "Pat" O'Callaghan (28 January 1906 – 1 December 1991) was an Irish athlete and Olympic gold medallist. He was the first athlete from Ireland to win an Olympic medal under the Irish flag rather than the British. In sport he then became regarded as one of Ireland's greatest-ever athletes.Early and private life

Pat O'Callaghan was born in the townland of Knockaneroe, near Kanturk, County Cork, on 28 January 1906, the second of three sons born to Paddy O'Callaghan, a farmer, and Jane Healy. He began his education at the age of two at Derrygalun national school. O'Callaghan progressed to secondary school in Kanturk and at the age of fifteen he won a scholarship to the Patrician Academy in Mallow. During his year in the Patrician Academy he cycled the 32-mile round trip from Derrygalun every day and he never missed a class. O'Callaghan subsequently studied medicine at the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin. Following his graduation in 1926 he joined the Royal Air Force Medical Service. He returned to Ireland in 1928 and set up his own medical practice in Clonmel, County Tipperary where he worked until his retirement in 1984.O'Callaghan was also a renowned field sports practitioner, greyhound trainer and storyteller.Sporting career

Early sporting life

O’Callaghan was born into a family that had a huge interest in a variety of different sports. His uncle, Tim Vaughan, was a national sprint champion and played Gaelic football with Cork in 1893. O’Callaghan's eldest brother, Seán, also enjoyed football as well as winning a national 440 yards hurdles title, while his other brother, Con, was also regarded as a gifted runner, jumper and thrower. O’Callaghan's early sporting passions included hunting, poaching and Gaelic football. He was regarded as an excellent midfielder on the Banteer football team, while he also lined out with the Banteer hurling team. At university in Dublin O’Callaghan broadened his sporting experiences by joining the local senior rugby club. This was at a time when the Gaelic Athletic Association ‘ban’ forbade players of Gaelic games from playing "foreign sports". It was also in Dublin that O’Callaghan first developed an interest in hammer-throwing. In 1926, he returned to his native Duhallow where he set up a training regime in hammer-throwing. Here he fashioned his own hammer by boring a one-inch hole through a 16 lb shot and filling it with the ball-bearing core of a bicycle pedal. He also set up a throwing circle in a nearby field where he trained. In 1927, O’Callaghan returned to Dublin where he won that year's hammer championship with a throw of 142’ 3”. In 1928, he retained his national title with a throw of 162’ 6”, a win which allowed him to represent the Ireland at the forthcoming Olympic Games in Amsterdam. On the same day, O’Callaghan's brother, Con, won the shot put and the decathlon and also qualified for the Olympic Games. Between winning his national title and competing in the Olympic Games O’Callaghan improved his throwing distance by recording a distance of 166’ 11” at the Royal Ulster ConstabularySports in Belfast.1928 Olympic Games

In the summer of 1928, the three O’Callaghan brothers paid their own fares when travelling to the Olympic Games in Amsterdam. Pat O’Callaghan finished in sixth place in the preliminary round and started the final with a throw of 155’ 9”. This put him in third place behind Ossian Skiöld of Sweden, but ahead of Malcolm Nokes, the favourite from Great Britain. For his second throw, O’Callaghan used the Swede's own hammer and recorded a throw of 168’ 7”. This was 4’ more than Skoeld's throw and resulted in a first gold medal for O’Callaghan and for Ireland. The podium presentation was particularly emotional as it was the first time at an Olympic Games that the Irish tricolour was raised and Amhrán na bhFiann was played.Success in Ireland

After returning from the Olympic Games, O’Callaghan cemented his reputation as a great athlete with additional successes between 1929 and 1932. In the national championships of 1930 he won the hammer, shot-putt, 56 lbs without follow, 56 lbs over-the-bar, discus and high jump. In the summer of 1930, O’Callaghan took part in a two-day invitation event in Stockholm where Oissian Skoeld was expected to gain revenge on the Irishman for the defeat in Amsterdam. On the first day of the competition, Skoeld broke his own European record with his very first throw. O’Callaghan followed immediately and overtook him with his own first throw and breaking the new record. On the second day of the event both O’Callaghan and Skoeld were neck-and-neck, when the former, with his last throw, set a new European record of 178’ 8” to win.1932 Summer Olympics

By the time the 1932 Summer Olympics came around O’Callaghan was regularly throwing the hammer over 170 feet. The Irish team were much better organised on that occasion and the whole journey to Los Angeles was funded by a church-gate collection. Shortly before departing on the 6,000-mile boat and train journey across the Atlantic O’Callaghan collected a fifth hammer title at the national championships. On arrival in Los Angeles O’Callaghan's preparations of the defence of his title came unstuck. The surface of the hammer circle had always been of grass or clay and throwers wore field shoes with steel spikes set into the heel and sole for grip. In Los Angeles, however, a cinder surface was to be provided. The Olympic Committee of Ireland had failed to notify O’Callaghan of this change. Consequently, he came to the arena with three pairs of spiked shoes for a grass or clay surface and time did not permit a change of shoe. He wore his shortest spikes, but found that they caught in the hard gritty slab and impeded his crucial third turn. In spite of being severely impeded, he managed to qualify for the final stage of the competition with his third throw of 171’ 3”. While the final of the 400m hurdles was delayed, O’Callaghan hunted down a hacksaw and a file in the groundskeeper's shack and he cut off the spikes. O’Callaghan's second throw reached a distance of 176’ 11”, a result which allowed him to retain his Olympic title. It was Ireland's second gold medal of the day as Bob Tisdall had earlier won a gold medal in the 400m hurdles.Retirement

Due to the celebrations after the Olympic Games O’Callaghan didn't take part in the national athletic championships in Ireland in 1933. In spite of that he still worked hard on his training and he experimented with a fourth turn to set a new European record at 178’ 9”. By this stage O’Callaghan was rated as the top thrower in the world by the leading international sports journalists. In the early 1930s controversy raged between the British AAA and the National Athletic and Cycling Association of Ireland (NACAI). The British AAA claimed jurisdiction in Northern Ireland while the NACAI claimed jurisdiction over the entire island of Ireland regardless of political division. The controversy came to a head in the lead-up to the 1936 Summer Olympics when the IAAF finally disqualified the NACAI. O’Callaghan remained loyal to the NACAI, a decision which effectively brought an end to his international athletic career. No Irish team travelled to the 1936 Olympic Games, however O’Callaghan travelled to Berlin as a private spectator. After Berlin, O’Callaghan's international career was over. He declined to join the new Irish Amateur Athletics Union (IAAU) or subsequent IOC recognised Amateur Athletics Union of Eire (AAUE) and continued to compete under NACAI rules. At Fermoy in 1937 he threw 195’ 4” – more than seven feet ahead of the world record set by his old friend Paddy 'Chicken' Ryan in 1913. This record, however, was not ratified by the AAUE or the IAAF. In retirement O’Callaghan remained interested in athletics. He travelled to every Olympic Games up until 1988 and enjoyed fishing and poaching in Clonmel. He died on 1 December 1991.Legacy

O'Callaghan was the flag bearer for Ireland at the 1932 Olympics. In 1960, he became the first person to receive the Texaco Hall of Fame Award. He was made a Freeman of Clonmel in 1984, and was honorary president of Commercials Gaelic Football Club. The Dr. Pat O'Callaghan Sports Complex at Cashel Rd, Clonmel which is the home of Clonmel Town Football Club is named after him, and in January 2007 his statue was raised in Banteer, County Cork.

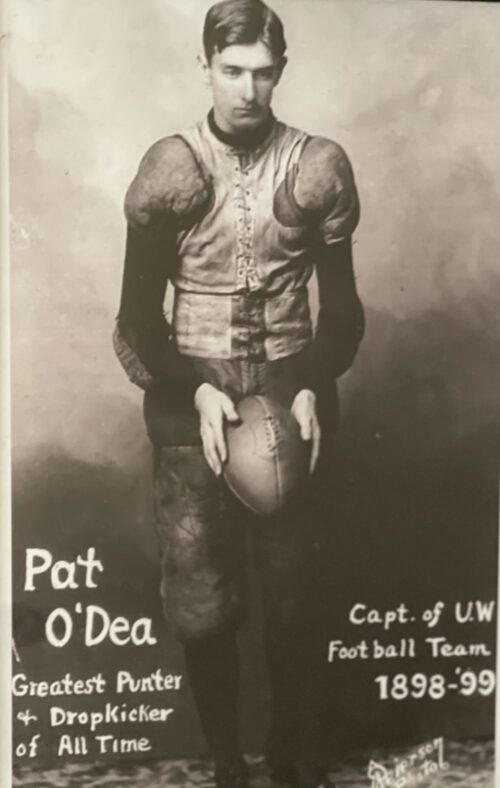

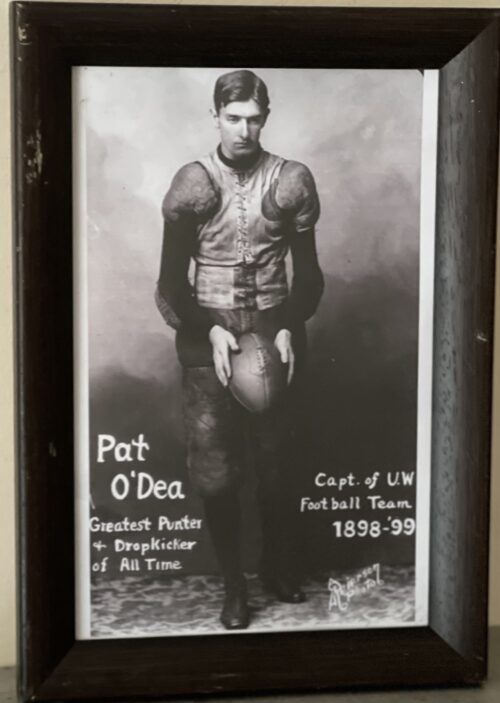

25cm x 35cm. Limerick Patrick John "Kangaroo Kicker" O'Dea (17 March 1872 – 5 April 1962) was an Irish-Australian rules and American footballplayer and coach. An Australian by birth, O'Dea played Australian rules football for the Melbourne Football Club in the Victorian Football Association (VFA). In 1898 and 1899, O'Dea played American football at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the United States, where he excelled in the kicking game. He then served as the head football coach at the University of Notre Dame from 1900 to 1901 and at the University of Missouri in 1902, compiling a career college footballrecord of 19–7–2. O'Dea was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame as a player in 1962.

25cm x 35cm. Limerick Patrick John "Kangaroo Kicker" O'Dea (17 March 1872 – 5 April 1962) was an Irish-Australian rules and American footballplayer and coach. An Australian by birth, O'Dea played Australian rules football for the Melbourne Football Club in the Victorian Football Association (VFA). In 1898 and 1899, O'Dea played American football at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the United States, where he excelled in the kicking game. He then served as the head football coach at the University of Notre Dame from 1900 to 1901 and at the University of Missouri in 1902, compiling a career college footballrecord of 19–7–2. O'Dea was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame as a player in 1962.Early life

O'Dea was born in Kilmore, Victoria, Australia to an Irish-born father and a Victorian-born mother. He was the third child of seven children. As a child he attended Christian Brothers College and Xavier College. As a 16-year-old he received a bronze medallion from the Royal Humane Society of Australasia for rescuing a woman at Mordialloc beach.Playing career

O'Dea played American football at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he was their star fullback from 1896–1899 and captained the 1898 and 1899 teams. In those days fullbacks punted and often did the placekicking. In the 1898 edition of the Northwestern game, which was played in a blizzard, he drop kicked a 62-yard field goal, and had a 116-yard punt. This earned him the nickname "Kangaroo Kicker". Wisconsin then headed into a Thanksgiving Day showdown with 1898 Western champions Michigan with only the narrow loss to Yale marring their record. New songs were composed for the occasion including “Oh, Pat O’Dea” to the popular tune “Margery”. The chorus ran: "Oh Pat O’Dea, oh Pat O’Dea, We love you more and more. Oh Pat O’Dea, oh Pat O’Dea, You’re the boy that we adore; Your leg is ever sure and true, And always kicks a goal or two. The team and rooters worship you. Oh Pat O’Dea." The final verse concluded: "To this brave lad forever we shall proudly sing. He is the boy we love. And in the games we play The cry “O’Dea, ”We’ll yell to every foe, because their game will show There is no other lad to see like Pat O’Dea. The East and West will surely have to see That we can’t lose in Patrick’s shoes, For he’s the only boy in all this land so free. The famous punter, Pat O’Dea." In the 1899 game, he returned a kickoff 90 yards for a touchdown, and had four field goals. He was selected as an All-American team member in 1899.Coaching career

Notre Dame

From 1900 to 1901, O'Dea coached at the University of Notre Dame, and compiled a 14–4–2 record.Missouri

O'Dea was the tenth head football coach for the University of Missouri–Columbia Tigers located in Columbia, Missouri and he held that position for the 1902 season. His career coaching record at Missouri was 5 wins, 3 losses, and 0 ties. This ranks him 22nd at Missouri in total wins and tenth at Missouri in winning percentage.Later life

After coaching, he disappeared from public view in 1917, having decided that he didn't like being treated as a celebrity, and it was assumed by Wisconsin fans that O'Dea had died fighting in World War I. In 1934, he was discovered living under an assumed name in California and came back to Wisconsin to a hero's welcome. He later appeared on Bob Hope's All-American football team announcement shows. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame on 3 April 1962. He died the next day at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center. Pat O'Dea died on 4 April 1962 at the age of 90 after an illness. While he was in hospital he received a get-well message from President John Kennedy. O'Dea's obituary in the New York Times commented on his kicking achievements including a 110-yard punt, though against Minnesota in 1897 and not Yale in 1899, and his 62-yard goal against Northwestern in 1898.

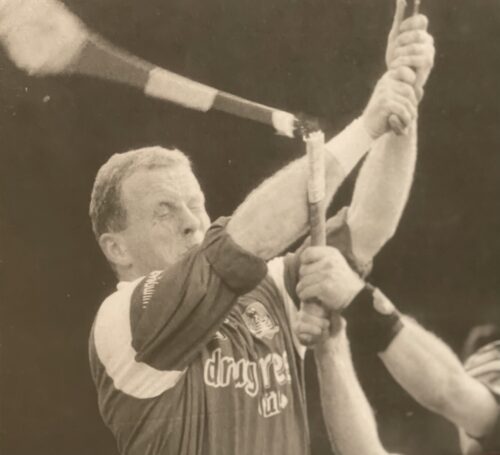

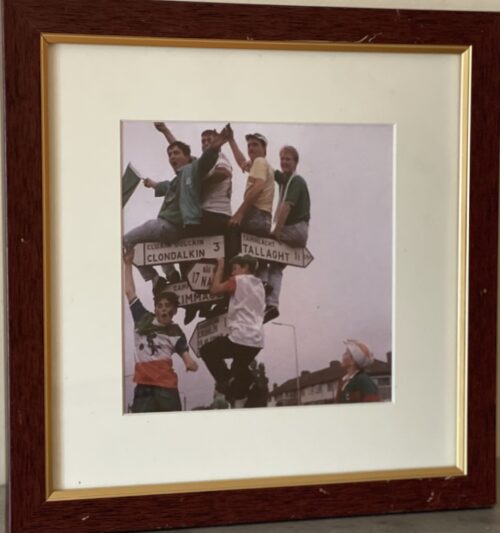

30cm x 30cm If ever a time symbolised flag-waving, delirious, green white and orange national pride, Italia '90 was that time. It all came down to one single glorious moment on a steamy June night in the Stadio Luigi Ferraris in Genoa when Packie Bonner saved that penalty and a deafening Une Voce roar erupted, ricocheting through every home and bar across Ireland. Seconds later when David O'Leary's winning penalty unleashed tears of unbridled joy Irish tricolours billowed like crazy in the breezeless stands and cascaded from the terraces to seemingly endless choruses of 'Olé, Olé, Olé, Olé'. We had made it through to the quarter-finals of the World Cup but we might as well have won and no-one wanted to let that moment go. Back home, cars catapulted onto the streets of every town and village with horns honking and flags wavering precariously from rolled-down windows. In Donegal an impromptu motorcade, suddenly, impulsively headed for Packie's home place in the Rosses, where fans danced in the front garden and waved the tricolour. It was an epic display of patriotic fervour and a defining moment, not just for Irish football but for our sense of identity. Historian and author, John Dorney describes it as the moment when Irish identity and international football collided. In his analysis of the era, he concludes that the Irish team's English manager, Jack Charlton neither knew nor cared about the multiple divisions in Irish society. Likewise, many of the team had been born in England of Irish ancestry and were "a clean slate" without baggage.

30cm x 30cm If ever a time symbolised flag-waving, delirious, green white and orange national pride, Italia '90 was that time. It all came down to one single glorious moment on a steamy June night in the Stadio Luigi Ferraris in Genoa when Packie Bonner saved that penalty and a deafening Une Voce roar erupted, ricocheting through every home and bar across Ireland. Seconds later when David O'Leary's winning penalty unleashed tears of unbridled joy Irish tricolours billowed like crazy in the breezeless stands and cascaded from the terraces to seemingly endless choruses of 'Olé, Olé, Olé, Olé'. We had made it through to the quarter-finals of the World Cup but we might as well have won and no-one wanted to let that moment go. Back home, cars catapulted onto the streets of every town and village with horns honking and flags wavering precariously from rolled-down windows. In Donegal an impromptu motorcade, suddenly, impulsively headed for Packie's home place in the Rosses, where fans danced in the front garden and waved the tricolour. It was an epic display of patriotic fervour and a defining moment, not just for Irish football but for our sense of identity. Historian and author, John Dorney describes it as the moment when Irish identity and international football collided. In his analysis of the era, he concludes that the Irish team's English manager, Jack Charlton neither knew nor cared about the multiple divisions in Irish society. Likewise, many of the team had been born in England of Irish ancestry and were "a clean slate" without baggage.