Castiron replica of a signpost to Croke Park, the headquarters of the GAA and one of the most famous sporting venues in the world.

Dimensions : 40cm x 10cm 1.25kg

Croke Park (

Irish:

Páirc an Chrócaigh) is a

Gaelic games stadium located in

Dublin, Ireland. Named after Archbishop

Thomas Croke, it is sometimes called

Croker by GAA fans and locals.

It serves as both the principal stadium and headquarters of the

Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). Since 1891

the site has been used by the GAA to host Gaelic sports, including the annual All-Ireland in

Gaelic football and

hurling.

A major

expansion and redevelopment of the stadium ran from 1991–2005, raising capacity to its current 82,300 spectators.

This makes Croke Park the

third-largest stadium in Europe, and the largest not usually used for

association football.

Other events held at the stadium include the opening and closing ceremonies of the

2003 Special Olympics, and numerous musical concerts. In 2012, Irish pop group

Westlife sold out the stadium in record-breaking time: less than 5 minutes. From 2007–10, Croke Park hosted home matches of the

Ireland national rugby union team and the

Republic of Ireland national football team, while their new

Aviva Stadium was constructed. This use of Croke Park for non-Gaelic sports

was controversial and required temporary changes to GAA rules. In June 2012, the stadium hosted the closing ceremony of the

50th International Eucharistic Congress during which

Pope Benedict XVI gave an address over video link.

City and Suburban Racecourse

A fireworks and light display was held in Croke Park in front of 79,161 fans on Saturday 31 January 2009 to mark the GAA's 125th anniversary

The area now known as Croke Park was owned in the 1880s by Maurice Butterly and known as the City and Suburban Racecourse, or Jones' Road sports ground. From 1890 it was also used by the

Bohemian Football Club. In 1901 Jones' Road hosted the

IFA Cup football final when

Cliftonville defeated

Freebooters.

History

Recognising the potential of the Jones' Road sports ground a journalist and GAA member, Frank Dineen, borrowed much of the £3,250 asking price and bought the ground in 1908. In 1913 the GAA came into exclusive ownership of the plot when they purchased it from Dineen for £3,500. The ground was then renamed Croke Park in honour of Archbishop

Thomas Croke, one of the GAA's first patrons.

In 1913, Croke Park had only two stands on what is now known as the Hogan stand side and grassy banks all round. In 1917, a grassy hill was constructed on the railway end of Croke Park to afford patrons a better view of the pitch. This terrace was known originally as Hill 60, later renamed Hill 16 in memory of the 1916

Easter Rising. It is erroneously believed to have been built from the ruins of the GPO, when it was constructed the previous year in 1915.

In the 1920s, the GAA set out to create a high capacity stadium at Croke Park. Following the Hogan Stand, the Cusack Stand, named after

Michael Cusack from Clare (who founded the GAA and served as its first secretary), was built in 1927. 1936 saw the first double-deck Cusack Stand open with 5,000 seats, and concrete terracing being constructed on Hill 16. In 1952 the Nally Stand was built in memorial of

Pat Nally, another of the GAA founders. Seven years later, to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the GAA, the first cantilevered "New Hogan Stand" was opened.

The highest attendance ever recorded at an All-Ireland Senior Football Championship Final was 90,556 for

Offaly v

Down in

1961. Since the introduction of seating to the Cusack stand in 1966, the largest crowd recorded has been 84,516.

Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday remembrance plaque

During the

Irish War of Independence on 21 November 1920 Croke Park was the scene of a massacre by the

Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). The Police, supported by the

British Auxiliary Division, entered the ground and began shooting into the crowd, killing or fatally wounding 14 civilians during a

Dublin-

Tipperary Gaelic football match. The dead included 13 spectators and Tipperary player

Michael Hogan. Posthumously, the Hogan stand built in 1924 was named in his honour. These shootings, on the day which became known as

Bloody Sunday, were a reprisal for the killing of 15 people associated with the

Cairo Gang, a group of

British Intelligence officers, by

Michael Collins' '

squad' earlier that day.

Dublin Rodeo

In 1924, American

rodeo promoter,

Tex Austin, staged the Dublin Rodeo,

Ireland's first professional rodeo at Croke Park Stadium.

For seven days, with two shows each day from August 18 to August 24, sell out crowds saw cowboys and cowgirls from Canada, the United States, Mexico, Argentina and Australia compete for rodeo championship titles.

Canadian bronc riders such as Andy Lund and his brother Art Lund, trick riders such as Ted Elder

and Vera McGinnis were among the contestants.

British Pathe filmed some of the rodeo events.

Stadium design

In 1984 the organisation decided to investigate ways to increase the capacity of the old stadium. The design for an 80,000 capacity stadium was completed in 1991. Gaelic sports have special requirements as they take place on a large field. A specific requirement was to ensure the spectators were not too far from the field of play. This resulted in the three-tier design from which viewing games is possible: the main concourse, a premium level incorporating hospitality facilities and an upper concourse. The premium level contains restaurants, bars and conference areas. The project was split into four phases over a 14-year period. Such was the importance of Croke Park to the GAA for hosting big games, the stadium did not close during redevelopment. During each phase different parts of the ground were redeveloped, while leaving the rest of the stadium open. Big games, including the annual All-Ireland Hurling and Football finals, were played in the stadium throughout the development.

The outside of the Cusack Stand

Phase one – New Cusack Stand

The first phase of construction was to build a replacement for Croke Park's Cusack Stand. A lower deck opened for use in 1994. The upper deck opened in 1995. Completed at a cost of £35 million, the new stand is 180 metres long, 35 metres high, has a capacity for 27,000 people and contains 46 hospitality suites. The new Cusack Stand contains three tiers from which viewing games is possible: the main concourse, a premium level incorporating hospitality facilities and finally an upper concourse. One end of the pitch was closer to the stand after this phase, as the process of slightly re-aligning the pitch during the redevelopment of the stadium began. The works were carried out by

Sisk Group.

Phase two – Davin Stand

Phase Two of the development started in late 1998 and involved extending the new Cusack Stand to replace the existing Canal End terrace. It involved reacquiring a rugby pitch that had been sold to

Belvedere College in 1910 by Frank Dineen. In payment and part exchange, the college was given the nearby Distillery Road sportsgrounds.

[19]

It is now known as The Davin Stand (Irish:

Ardán Dáimhím), after

Maurice Davin, the first president of the GAA. This phase also saw the creation of a tunnel which was later named the Ali tunnel in honour of

Muhammad Ali and

his fight against Al Lewis in July 1972 in Croke Park.

Phase three – Hogan Stand

Phase Three saw the building of the new Hogan Stand. This required a greater variety of spectator categories to be accommodated including general spectators, corporate patrons, VIPs, broadcast and media services and operation staff. Extras included a fitted-out mezzanine level for VIP and Ard Comhairle (Where the dignitaries sit) along with a top-level press media facility. The end of Phase Three took the total spectator capacity of Croke Park to 82,000.

Phase four – Nally Stand & Nally End/Dineen Hill 16 terrace

After the 2003 Special Olympics, construction began in September 2003 on the final phase, Phase Four. This involved the redevelopment of the Nally Stand, named after the athlete

Pat Nally, and Hill 16 into a new Nally End/Dineen Hill 16 terrace. While the name Nally had been used for the stand it replaced, the use of the name Dineen was new, and was in honour of

Frank Dineen, who bought the original stadium for the GAA in 1908, giving it to them in 1913. The old Nally Stand was taken away and reassembled in Pairc Colmcille, home of Carrickmore GAA in

County Tyrone.

The phase four development was officially opened by the then GAA President

Seán Kelly on 14 March 2005. For logistical reasons (and, to a degree, historical reasons), and also to provide cheaper high-capacity space, the area is a terrace rather than a seated stand, the only remaining standing-room in Croke Park. Unlike the previous Hill, the new terrace was divided into separate sections – Hill A (Cusack stand side), Hill B (behind the goals) and the Nally terrace (on the site of the old Nally Stand). The fully redeveloped Hill has a capacity of around 13,200, bringing the overall capacity of the stadium to 82,300. This made the stadium the second biggest in the EU after the

Camp Nou, Barcelona. However, London's new Wembley stadium has since overtaken Croke Park in second place. The presence of terracing meant that for the brief period when Croke Park hosted international

association football during 2007–2009, the capacity was reduced to approximately 73,500, due to FIFA's statutes stating that competitive games must be played in all-seater stadiums.

Pitch

Croke Park floodlights in use during Six Nations Championship match

The pitch in Croke Park is a soil pitch that replaced the

Desso GrassMaster pitch laid in 2002.

This replacement was made after several complaints by players and managers that the pitch was excessively hard and far too slippery.

Since January 2006, a special growth and lighting system called the SGL Concept has been used to assist grass growing conditions, even in the winter months. The system, created by Dutch company SGL (Stadium Grow Lighting), helps in controlling and managing all pitch growth factors, such as light, temperature, CO

2, water, air and nutrients.

Floodlighting

With the

2007 Six Nations clash with

France and possibly other matches in subsequent years requiring lighting the GAA installed

floodlights in the stadium (after planning permission was granted). Indeed, many other GAA grounds around the country have started to erect floodlights as the organisation starts to hold games in the evenings, whereas traditionally major matches were played almost exclusively on Sunday afternoons. The first game to be played under these lights at Croke Park was a

National Football League Division One match between

Dublin and

Tyrone on 3 February 2007 with Tyrone winning in front of a capacity crowd of over 81,000 – which remains a record attendance for a National League game, with Ireland's Six Nations match with France following on 11 February.

Temporary floodlights were installed for the

American Bowl game between

Chicago Bears and

Pittsburgh Steelers on the pitch in 1997, and again for the

2003 Special Olympics.

Concert

U2's Vertigo Tour at Croke Park in 2005

U2's 360° Tour at Croke Park in 2009

| 29 June 1985 |

U2 |

In Tua Nua, R.E.M., The Alarm, Squeeze |

The Unforgettable Fire Tour |

57,000 |

First Irish act to have a headline concert. Part of the concert was filmed for the group's documentary Wide Awake in Dublin. |

| 28 June 1986 |

Simple Minds |

|

Once Upon A Time Tour |

|

Guest appearance by Bono |

| 27 June 1987 |

U2 |

Light A Big Fire, The Dubliners, The Pogues, Lou Reed |

The Joshua Tree Tour |

114,000 |

|

| 28 June 1987 |

Christy Moore, The Pretenders, Lou Reed, Hothouse Flowers |

|

| 28 June 1996 |

Tina Turner |

Brian Kennedy |

Wildest Dreams Tour |

40,000/40,000 |

|

| 16 May 1997 |

Garth Brooks |

|

World Tour II |

|

|

| 18 May 1997 |

|

|

| 29 May 1998 |

Elton John & Billy Joel |

|

Face to Face 1998 |

|

|

| 30 May 1998 |

|

|

|

| 24 June 2005 |

U2 |

The Radiators from Space, The Thrills, The Bravery, Snow Patrol, Paddy Casey, Ash |

Vertigo Tour |

246,743 |

|

| 25 June 2005 |

|

| 27 June 2005 |

|

| 20 May 2006 |

Bon Jovi |

Nickelback |

Have a Nice Day Tour |

81,327 |

|

| 9 June 2006 |

Robbie Williams |

Basement Jaxx |

Close Encounters Tour |

|

|

| 6 October 2007 |

The Police |

Fiction Plane |

The Police Reunion Tour |

81,640 |

Largest attendance of the tour. |

| 31 May 2008 |

Celine Dion |

Il Divo |

Taking Chances World Tour |

69,725 |

Largest attendance for a solo female act |

| 1 June 2008 |

Westlife |

Shayne Ward |

Back Home Tour |

85,000 |

Second Irish act to have a headline concert. Largest attendance of the tour. Part of the concert was filmed for the group's documentary and concert DVD 10 Years of Westlife - Live at Croke Park Stadium. |

| 14 June 2008 |

Neil Diamond |

|

|

|

|

| 13 June 2009 |

Take That |

The Script |

Take That Present: The Circus Live |

|

|

| 24 July 2009 |

U2 |

Glasvegas, Damien Dempsey |

U2 360° Tour |

243,198 |

|

| 25 July 2009 |

Kaiser Chiefs, Republic of Loose |

|

| 27 July 2009 |

Bell X1, The Script |

The performances of "New Year's Day" and "I'll Go Crazy If I Don't Go Crazy Tonight" were recorded for the group's live album U22 and for the band's remix album Artificial Horizon and the live EP Wide Awake in Europe, respectively. |

| 5 June 2010 |

Westlife |

Wonderland, WOW, JLS, Jedward |

Where We Are Tour |

86,500 |

Largest attendance of the tour. |

| 18 June 2011 |

Take That |

Pet Shop Boys |

Progress Live |

154,828 |

|

| 19 June 2011 |

|

| 22 June 2012 |

Westlife |

Jedward, The Wanted, Lawson |

Greatest Hits Tour |

187,808[24] |

The 23 June 2012 date broke the stadium record for selling out its tickets in four minutes. Eleventh largest attendance at an outdoor stadium worldwide. Largest attendance of the tour and the band's music career history. Part of the concert was filmed for the group's documentary and concert DVD The Farewell Tour - Live in Croke Park. |

| 23 June 2012 |

| 26 June 2012 |

Red Hot Chili Peppers |

Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds, The Vaccines |

I'm with You World Tour |

|

|

| 23 May 2014 |

One Direction |

5 Seconds of Summer |

Where We Are Tour |

235,008 |

|

| 24 May 2014 |

|

| 25 May 2014 |

|

| 20 June 2015 |

The Script & Pharrell Williams |

|

No Sound Without Silence Tour |

74,635 |

|

| 24 July 2015 |

Ed Sheeran |

|

x Tour |

162,308 |

|

| 25 July 2015 |

|

|

| 27 May 2016 |

Bruce Springsteen |

|

The River Tour 2016 |

160,188 |

|

| 29 May 2016 |

|

|

| 9 July 2016 |

Beyoncé |

Chloe x Halle, Ingrid Burley |

The Formation World Tour |

68,575 |

|

| 8 July 2017 |

Coldplay |

AlunaGeorge, Tove Lo |

A Head Full of Dreams Tour[25] |

80,398 |

|

| 22 July 2017 |

U2 |

Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds |

The Joshua Tree Tour 2017 |

80,901 |

|

| 17 May 2018 |

The Rolling Stones |

The Academic |

No Filter Tour |

64,823 |

|

| 15 June 2018 |

Taylor Swift |

Camila Cabello, Charli XCX |

Taylor Swift's Reputation Stadium Tour |

136.000 |

Swift became the first woman headline two concerts in a row there. |

| 16 June 2018 |

| 7 July 2018 |

Michael Bublé |

Emeli Sandé |

|

|

| 24 May 2019 |

Spice Girls |

Jess Glynne |

Spice World - 2019 UK Tour |

|

|

| 5 July 2019 |

Westlife |

James Arthur

Wild Youth |

The 20 Touror The Twenty Tour |

|

The 5 July 2019 date sold out its tickets in six minutes. Second date released were also sold out in under forty-eight hours. |

| 6 July 2019 |

Non-Gaelic games

There was great debate in Ireland regarding the use of Croke Park for sports other than those of the GAA. As the GAA was founded as a

nationalist organisation to maintain and promote indigenous Irish sport, it has felt honour-bound throughout its history to oppose other, foreign (in practice, British), sports. In turn, nationalist groups supported the GAA as the prime example of purely Irish sporting culture.

Until its abolition in 1971, rule 27 of the GAA constitution stated that a member of the GAA could be banned from playing its games if found to be also playing association football, rugby or

cricket. That rule was abolished but

rule 42 still prohibited the use of GAA property for games with interests in conflict with the interests of the GAA. The belief was that rugby and association football were in competition with Gaelic football and hurling, and that if the GAA allowed these sports to use their ground it might be harmful to Gaelic games, while other sports, not seen as direct competitors with Gaelic football and hurling, were permitted, such as the two games of

American football (

Croke Park Classic college football game between

The University of Central Florida and

Penn State, and an

American Bowl NFL preseason game between the

Chicago Bears and the

Pittsburgh Steelers) on the Croke Park pitch during the 1990s.

[27]

On 16 April 2005, a motion to temporarily relax rule No. 42 was passed at the GAA Annual Congress. The motion gives the GAA Central Council the power to authorise the renting or leasing of Croke Park for events other than those controlled by the Association, during a period when

Lansdowne Road – the venue for international soccer and rugby matches – was closed for redevelopment. The final result was 227 in favour of the motion to 97 against, 11 votes more than the required two-thirds majority.

In January 2006, it was announced that the GAA had reached agreement with the

Football Association of Ireland (FAI) and

Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU) to stage two Six Nations games and four soccer internationals at Croke Park in 2007 and in February 2007, use of the pitch by the FAI and the IRFU in 2008 was also agreed.

These agreements were within the temporary relaxation terms, as Lansdowne Road was still under redevelopment until 2010. Although the GAA had said that hosted use of Croke Park would not extend beyond 2008, irrespective of the redevelopment progress,

fixtures

for the

2009 Six Nations rugby tournament saw the Irish rugby team using Croke park for a third season. 11 February 2007 saw the first rugby union international to be played there. Ireland were leading France in a Six Nations clash, but lost 17–20 after conceding a last minute (converted) try.

Raphael Ibanez scored the first try in that match;

Ronan O'Gara scored Ireland's first ever try in Croke Park.

A second match between Ireland and

England on 24 February 2007 was politically symbolic because of the events of

Bloody Sunday in 1920.

There was considerable concern as to what reaction there would be to the singing of the British

national anthem "

God Save the Queen". Ultimately the anthem was sung without interruption or incident, and applauded by both sets of supporters at the match, which Ireland won by 43–13 (their largest ever win over England in rugby).

On 2 March 2010, Ireland played their final international rugby match against a Scotland team that was playing to avoid the wooden spoon and hadn't won a championship match against Ireland since 2001. Outside half, Dan Parks inspired the Scots to a 3-point victory and ended Irish Hopes of a triple crown.

On 24 March 2007, the first association football match took place at Croke Park. The

Republic of Ireland took on

Wales in

UEFA Euro 2008 qualifying Group D, with a

Stephen Ireland goal securing a

1–0 victory for the Irish in front of a crowd of 72,500. Prior to this, the

IFA Cup had been played at the then Jones' Road in 1901, but this was 12 years before the GAA took ownership.

Negotiations took place for the

NFL International Series's 2011 game to be held at Croke Park but the game was awarded to

Wembley Stadium.

World record attendance

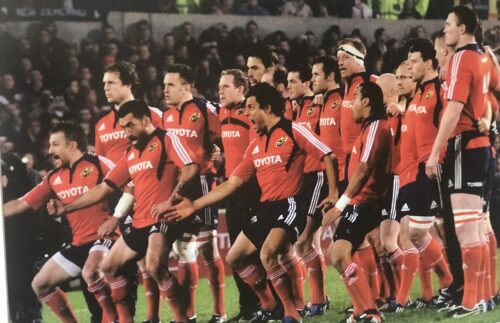

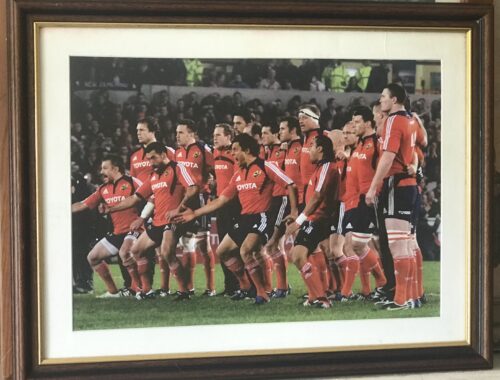

On 2 May 2009, Croke Park was the venue for a

Heineken Cup rugby

semi-final, in which

Leinster defeated

Munster 25–6. The attendance of 82,208 set a new world record attendance for a club rugby union game.

[35] This record stood until 31 March 2012 when it was surpassed by an

English Premiership game between

Harlequins and

Saracens at

Wembley Stadium which hosted a crowd of 83,761.

This was beaten again in 2016 in the

Top 14 final at the

Nou Camp which hosted a crowd of 99,124

Skyline tour

A walkway,

known under a sponsorship deal as

Etihad Skyline Croke Park, opened on 1 June 2012.

From 44 metres above the ground, it offers views of Dublin city and the surrounding area.

The

Olympic Torch was brought to the stadium and along the walkway on 6 June 2012.

GAA Hall of Fame

On 11 February 2013, the GAA opened the Hall of Fame section in the Croke Park museum. The foundation of the award scheme is the Teams of the Millennium

the football team which was announced in 1999 and

the hurling team in 2000 and all 30 players were inducted into the hall of fame along with

Limerick hurler

Eamonn Cregan and

Offaly footballer

Tony McTague who were chosen by a GAA sub-committee from the years 1970–74.

New inductees will be chosen on an annual basis from the succeeding five-year intervals as well as from years preceding 1970.

In April 2014, Kerry legend Mick O'Dwyer, Sligo footballer Micheál Kerins, along with hurlers Noel Skehan of Kilkenny and Pat McGrath of Waterford became the second group of former players to receive hall of fame awards.

Coursing operates in a highly regulated environment coupled with comprehensive rules directly applied by the ICC. It operates under a licence from the Minister of Arts, Heritage & the Gaeltacht, issued annually with a total of 22 conditions attached. Although our sport may take place only over the winter months and is sensitive to the hare breeding season, the protection and policing of preserves is a continuous activity and conducted on a voluntary basis. Quercus, the Belfast University research body reports that “Irish hares are 18 times more abundant in areas managed by the Irish Coursing Club than at similar sites in the wider countryside”.

Without regulated coursing there would be an increase of unregulated illegal hunting taking place throughout the year, with no organisation taking responsibility or interest in the overall well-being of the hare. If coursing clubs ceased to perform their functions, the hare population here would decline at a rapid rate as the proliferation of illegal hunting could easily rise to epidemic proportions as seen in the UK, where poaching and hare population decline are the order of the day.

Finally, I offer a quote I recently found that seems appropriate: “The future of coursing is so dependent on hare preservation that no effort should be spared by us to put it on an assured basis.”That was from an October 1924 edition of the Irish Coursing Calendar, now known as the Sporting Press newspaper.

The Irish Coursing Club has been, and will continue to be, deeply immersed in the conservation of the Irish Hare population, always seeking new ways to improve conservation in the face of loss of habitat due to the “advances” of our modern world and in spite of grossly uninformed efforts to ban it when no proven alternative conservation programmes are in place.

Coursing operates in a highly regulated environment coupled with comprehensive rules directly applied by the ICC. It operates under a licence from the Minister of Arts, Heritage & the Gaeltacht, issued annually with a total of 22 conditions attached. Although our sport may take place only over the winter months and is sensitive to the hare breeding season, the protection and policing of preserves is a continuous activity and conducted on a voluntary basis. Quercus, the Belfast University research body reports that “Irish hares are 18 times more abundant in areas managed by the Irish Coursing Club than at similar sites in the wider countryside”.

Without regulated coursing there would be an increase of unregulated illegal hunting taking place throughout the year, with no organisation taking responsibility or interest in the overall well-being of the hare. If coursing clubs ceased to perform their functions, the hare population here would decline at a rapid rate as the proliferation of illegal hunting could easily rise to epidemic proportions as seen in the UK, where poaching and hare population decline are the order of the day.

Finally, I offer a quote I recently found that seems appropriate: “The future of coursing is so dependent on hare preservation that no effort should be spared by us to put it on an assured basis.”That was from an October 1924 edition of the Irish Coursing Calendar, now known as the Sporting Press newspaper.

The Irish Coursing Club has been, and will continue to be, deeply immersed in the conservation of the Irish Hare population, always seeking new ways to improve conservation in the face of loss of habitat due to the “advances” of our modern world and in spite of grossly uninformed efforts to ban it when no proven alternative conservation programmes are in place.

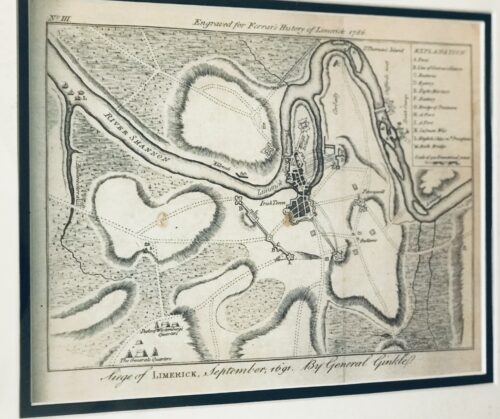

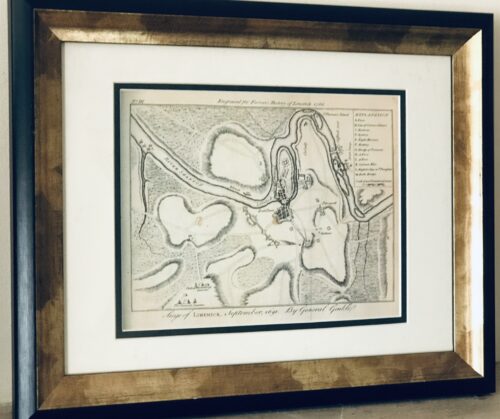

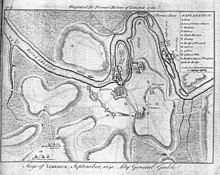

52cm x 60cm Coonagh Co Limerick

52cm x 60cm Coonagh Co Limerick