-

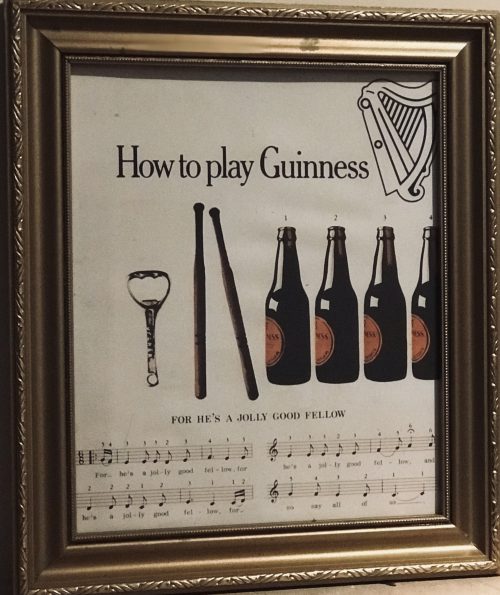

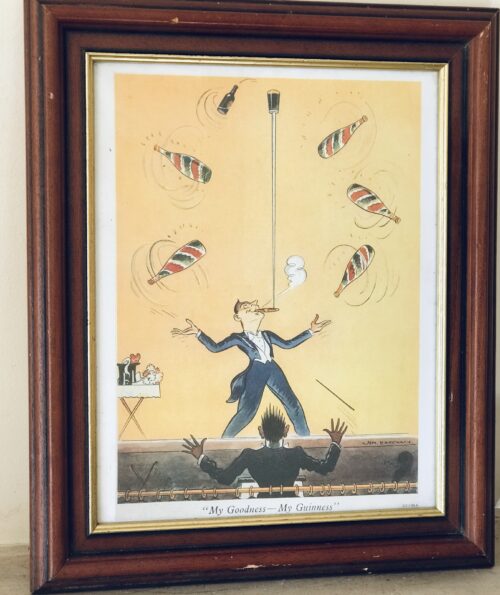

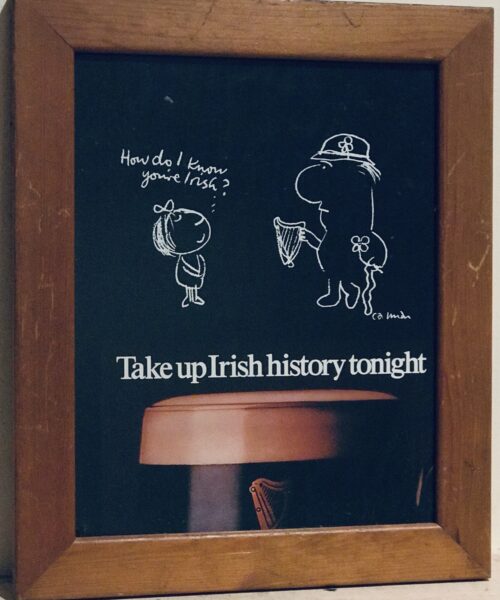

Charming How to play Guinness advert from the archives Dimensions 38cm x31cm Glazed Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm

Charming How to play Guinness advert from the archives Dimensions 38cm x31cm Glazed Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.” Origins : Dublin Dimensions : 43cm x 35cm -

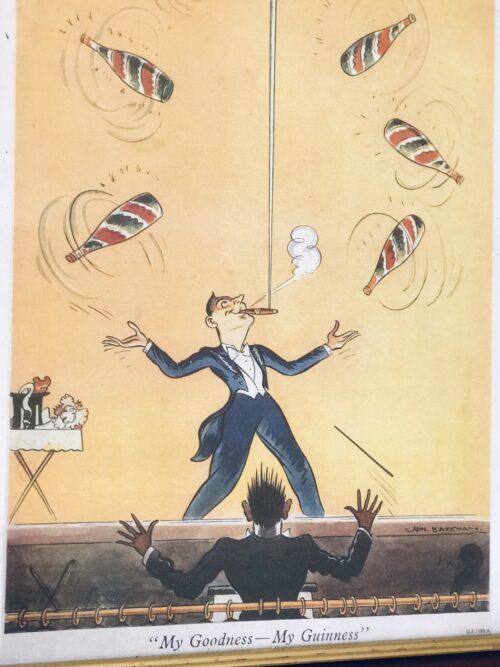

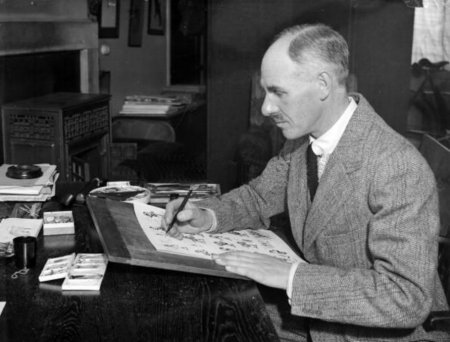

Wonderful HM Bateman Guinness Advert 44cm x 36cm

Wonderful HM Bateman Guinness Advert 44cm x 36cm H M Bateman 1887 - 1970

20th century cartoonist and caricaturist

To many admirers of the art of the cartoon, H.M.Bateman is the most original, the most various, the most brilliant – and, indeed, the funniest – genius of his times. Born in 1887, he was already drawing for publication in his early teens. Astonishingly prolific and inventive, everything he saw became material, so that his work can be read as a social history of Britain in the first half of the 20th Century and, to an extraordinary degree, as a kind of autobiography. His family and friends; his trips to the fair, to the seaside, abroad; his passions for the Music Hall, for tap-dancing, for boxing, for fishing, for golf; his desperate experiences in the First World War; his car, his house, his vacuum-cleaner; his triumphs and disasters over many years – all find their way in to his cartoons.

H M Bateman 1887 - 1970

20th century cartoonist and caricaturist

To many admirers of the art of the cartoon, H.M.Bateman is the most original, the most various, the most brilliant – and, indeed, the funniest – genius of his times. Born in 1887, he was already drawing for publication in his early teens. Astonishingly prolific and inventive, everything he saw became material, so that his work can be read as a social history of Britain in the first half of the 20th Century and, to an extraordinary degree, as a kind of autobiography. His family and friends; his trips to the fair, to the seaside, abroad; his passions for the Music Hall, for tap-dancing, for boxing, for fishing, for golf; his desperate experiences in the First World War; his car, his house, his vacuum-cleaner; his triumphs and disasters over many years – all find their way in to his cartoons.

This derangement, coupled with an absolute devotion to the surreal madness of Music Hall comedians, seems to have given him a new intensity, a highly charged way of working. At a stroke he did away with the conventional stillness – not to say stiffness - of cartoon figures and, as he himself put it, “went mad on paper”. Until this time conventional cartoons had been illustrated jokes – drawings with a few lines of text or dialogue underneath. Take away the dialogue and the drawing becomes meaningless, the joke lay in the words. From 1909 onwards Bateman drew no more illustrated jokes and so changed profoundly the art of the cartoon, invested it with a new freedom of line and expression. The drawing became funny in itself, self-explanatory. He made emotion the subject of his cartoons and the characters became actors expressing feeling, rather than illustrations to an idea. This was a new, histrionic, hyperbolic creative method and its effects are still apparent amongst some of our greatest cartoonists today. The second great and innovative contribution Bateman made to the art of the cartoon came during the First World War. He had been rejected by the army and retreated ill and deeply depressed to a remote inn on Dartmoor. But he worked prodigiously and started to produce, in 1916, astonishing strip cartoons that immediately gripped the public and the attention of his fellow artists. As a child he had been an avid reader of the new comic papers and these were, of course, full of comic strips. But these stories and adventures, full of invention and wonderful comic characters though they were, relied again on the story underneath, or speech-bubbles within, and were childish and simple. What Bateman did was to create self-contained strip cartoons without words, brilliant, innovative, cinematic comic stories, adult, often harsh and macabre, and frequently – at this period – to do with themes of guilt, punishment, retribution and death. Cartoons like The Boy Who Breathed on the Glass at the British Museum, The Guest Who Filled his Fountain Pen with Hotel Ink or Mexicans at Play are all wonderfully humorous but also harsh and complex and they come as a tremendous shock amongst the predictable pages of Punch or The Tatler. Nothing like them had been seen in this country before.

His style developed and changed radically over the years. From the graceful and rhythmical lines of his earlier work to the stark brilliance of his strip cartoons and the furious energy of his “Man Who ...” series, his essential qualities of superb draughtsmanship, astonishing observation and a profound appreciation of humanity’s foibles, are always married to a wonderful wit and narrative perfection. He told marvellously funny stories in pictures. He made three great and radical contributions to the art of the cartoon in this country. The first came in 1908 when, aged 21, he suffered a nervous breakdown probably caused by the dreadful choice he had to make between pushing forward with his career as a cartoonist, already much in demand, or trying to become a “serious” painter.

They contain those repeated descriptions of anger, consternation and disgust that became the hallmarks of the Bateman cartoon: eyeballs popping out of sockets, contorted bodies, figures prone or airborne. The protagonist is shown recoiling in horror from his actions and the attention focused on him, or else blithely carrying on, innocent of the outrage he has perpetrated and the world’s indignant roar. And the cartoons single out for scrutiny not only the individual who has caused such offence but, perhaps more interestingly, the society that condemns him.His third major influence on the history of the cartoon came in 1921 and continued for many years. It is, perhaps, the most famous of all his contributions and profoundly changed the landscape of humorous art: he started on his great series of “Man Who” cartoons. Looking back through his work it is apparent that he had been playing with this idea for many years, but the publication of The Guardsman Who Dropped It by the Tatler as a full colour centre -spread caused a sensation and engendered a series of cartoons that lasted for the rest of Bateman’s career. The majority of the Man Who cartoons describe some terrible social misdemeanour, some solecism or offence against accepted custom and behaviour.

Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.

Bateman became the most highly paid cartoonist in the country, sought after by advertisers, engaged in America and Australia, published in Europe. All this time, certainly until the late 1920s, he was producing his brilliant strip cartoons and a huge amount of other work in many different and interesting styles, but the Man Who cartoons came to define him, captured the public imagination and passed into the mythology of the nation. These are still in great demand and hardly a week goes by to this day without someone in the press referring to a “Bateman situation”. Astonishingly, right at the height of his fame, still in his forties, a few years before the Second World War, Bateman gave up all humorous art completely and slipped off quietly, alone, to pursue his old dream of becoming a “serious painter”. He died in his 84th year, still painting every day, out walking in the sunshine on Gozo, where he had lived simply and modestly in a quiet hotel, in the room with the finest view. The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks. -

Unusual advertising print -History of Irish Whiskey -featuring a cartoon type character and a bottle of Jameson Whiskey(Cooper's Croze). 48cm x 60cm Kilmallock Co Limerick Named in honour of Jameson's Master Cooper, Ger Buckley. The aim of this whiskey is to showcase the diversity of the barrels used at Jameson and the influence of the oak on the whiskey. Fittingly this is aged in a variety of barrels including ex-Bourbon, ex-Sherry and some virgin oak barrels. According to Irish Distillers: 'The Cooper’s Croze is a carefully crafted whiskey that effortlessly carries vanilla sweetness, rich fruit flavours, floral and spice notes and the undeniable influence of oak. You can take whiskey out of wood but you can never take the wood out of whiskey.'

Unusual advertising print -History of Irish Whiskey -featuring a cartoon type character and a bottle of Jameson Whiskey(Cooper's Croze). 48cm x 60cm Kilmallock Co Limerick Named in honour of Jameson's Master Cooper, Ger Buckley. The aim of this whiskey is to showcase the diversity of the barrels used at Jameson and the influence of the oak on the whiskey. Fittingly this is aged in a variety of barrels including ex-Bourbon, ex-Sherry and some virgin oak barrels. According to Irish Distillers: 'The Cooper’s Croze is a carefully crafted whiskey that effortlessly carries vanilla sweetness, rich fruit flavours, floral and spice notes and the undeniable influence of oak. You can take whiskey out of wood but you can never take the wood out of whiskey.' Origins:Kilmaley Co Clare Dimensions : Glazed

Origins:Kilmaley Co Clare Dimensions : Glazed -

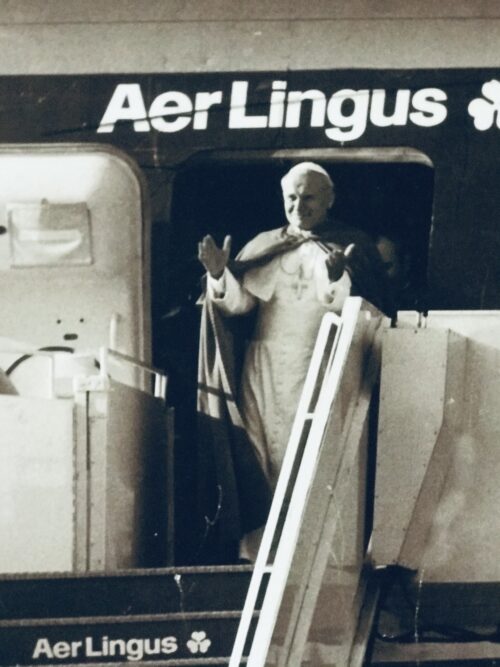

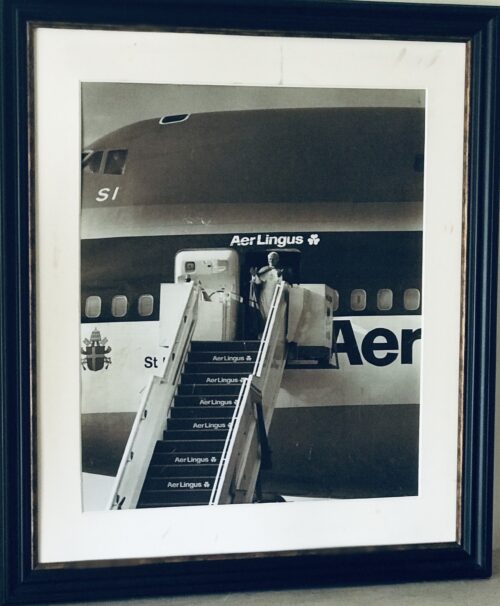

Nostalgic,atmospheric photo of Pope John Paul II arriving at Dublin Airport in 1979 on board an Aer Lingus 747-it was the first time a Pope had visited Ireland . 66cm x 56cm Gort Co Galway Pope John Paul visited Ireland from Saturday 29 September to Monday, 1 October 1979, the first trip to Ireland by a pope. Over 2.5 million people attended events in Dublin, Drogheda, Clonmacnoise, Galway, Knock, Limerick, and Maynooth. It was one of John Paul's first foreign visits as Pope, who had been elected in October 1978. The visit marked the centenary of the reputed apparitions at the Shrine of Knock in August 1 1878. An Aer Lingus Boeing 747, named St Patrick, brought Pope John Paul II from Rome to Dublin Airport. The Pope kissed the ground as he disembarked. After being greeted by the President of Ireland Patrick Hillery, the Pope flew by helicopter to Phoenix Park where he celebrated Mass for 1,250,000 people, one third of the population of the Republic of Ireland. Afterwards he travelled to Killineer, near Drogheda, where he led a Liturgy of the Word for 300,000 people, many from Northern Ireland. There the Pope appealed to the men of violence: "on my knees I beg you to turn away from the path of violence and return to the ways of peace". The Pope had hoped to visit Armagh, but the security situation in Northern Ireland rendered it impossible. Drogheda was selected as an alternative venue as it is situated in the Catholic Archdiocese of Armagh. Returning to Dublin that evening, the Pope was greeted by 750,000 people as he travelled in an open top popemobile through the city centre and visited Áras an Uachtaráin, the residence of the Irish President.His final engagement was a meeting with journalists at the Dominican Convent in Cabra.The journalists from the international media broke into a spontaneous rendition of 'For he's a jolly good fellow' when the Pope arrived. Pope John Paul spent the night at the nearby Apostolic Nunciature on the Navan Road in Cabra. Pope John Paul began the second day of his tour with a short visit to the ancient monastery at Clonmacnoise in County Offaly.With 20,000 in attendance, he spoke of how the ruins were "still charged with a great mission".Later that morning he celebrated a Youth Mass for 300,000 at Ballybrit Racecourse in Galway. It was here that the Pope uttered perhaps the most memorable line of his visit: "Young people of Ireland, I love you".That afternoon, he travelled by helicopter to Knock Shrine in County Mayo which he described as "the goal of my journey to Ireland".The outdoor Mass at the shrine was attended by 450,000. The Pope met with the sick and elevated the church to the title of Basilica. He lit a candle at the Gable Wall for the families of Ireland. Monsignor James Horan, instrumental in the shrine's development, welcomed the Pope to Knock. The final day of the visit began with a brief early morning visit to St Patrick's College, Maynooth, the National Seminary, in County Kildare.Some 80,000 people joined 1,000 seminarians on the grounds of the college for the brief visit. A dense fog delayed the Pope's arrival from Dublin by helicopter. The final Mass of the Pope's visit to Ireland was celebrated at Greenpark Racecoursein Limerick before 400,000 people, many more than had been expected. The Mass was offered for the people of Munster. Pope John Paul left Ireland from nearby Shannon Airport travelling to Boston where he began a six-day tour of the United States. Pope John Paul delivered 22 homilies and addresses during the course of this visit, including a televised message for the sick broadcast on RTÉ on the evening of his arrival in Ireland. Audio files of his more significant speeches are preserved on the website of the Irish Catholic Bishops Conference.Many of the temporary fixtures and ornaments at the public masses were auctioned two months after the visit to help defray its cost. A Time Remembered - The Visit of Pope John Paul II to Ireland was produced by RTÉ in 2005. Many children were named John and Paul in the aftermath of the papal visit. There were many Johns and Pauls beforehand but there was a huge increase in the amount of children called after the Pope's taken names. Some children were also given both names as their Christian name and were known as John Paul in honour of the Pope's visit.

Nostalgic,atmospheric photo of Pope John Paul II arriving at Dublin Airport in 1979 on board an Aer Lingus 747-it was the first time a Pope had visited Ireland . 66cm x 56cm Gort Co Galway Pope John Paul visited Ireland from Saturday 29 September to Monday, 1 October 1979, the first trip to Ireland by a pope. Over 2.5 million people attended events in Dublin, Drogheda, Clonmacnoise, Galway, Knock, Limerick, and Maynooth. It was one of John Paul's first foreign visits as Pope, who had been elected in October 1978. The visit marked the centenary of the reputed apparitions at the Shrine of Knock in August 1 1878. An Aer Lingus Boeing 747, named St Patrick, brought Pope John Paul II from Rome to Dublin Airport. The Pope kissed the ground as he disembarked. After being greeted by the President of Ireland Patrick Hillery, the Pope flew by helicopter to Phoenix Park where he celebrated Mass for 1,250,000 people, one third of the population of the Republic of Ireland. Afterwards he travelled to Killineer, near Drogheda, where he led a Liturgy of the Word for 300,000 people, many from Northern Ireland. There the Pope appealed to the men of violence: "on my knees I beg you to turn away from the path of violence and return to the ways of peace". The Pope had hoped to visit Armagh, but the security situation in Northern Ireland rendered it impossible. Drogheda was selected as an alternative venue as it is situated in the Catholic Archdiocese of Armagh. Returning to Dublin that evening, the Pope was greeted by 750,000 people as he travelled in an open top popemobile through the city centre and visited Áras an Uachtaráin, the residence of the Irish President.His final engagement was a meeting with journalists at the Dominican Convent in Cabra.The journalists from the international media broke into a spontaneous rendition of 'For he's a jolly good fellow' when the Pope arrived. Pope John Paul spent the night at the nearby Apostolic Nunciature on the Navan Road in Cabra. Pope John Paul began the second day of his tour with a short visit to the ancient monastery at Clonmacnoise in County Offaly.With 20,000 in attendance, he spoke of how the ruins were "still charged with a great mission".Later that morning he celebrated a Youth Mass for 300,000 at Ballybrit Racecourse in Galway. It was here that the Pope uttered perhaps the most memorable line of his visit: "Young people of Ireland, I love you".That afternoon, he travelled by helicopter to Knock Shrine in County Mayo which he described as "the goal of my journey to Ireland".The outdoor Mass at the shrine was attended by 450,000. The Pope met with the sick and elevated the church to the title of Basilica. He lit a candle at the Gable Wall for the families of Ireland. Monsignor James Horan, instrumental in the shrine's development, welcomed the Pope to Knock. The final day of the visit began with a brief early morning visit to St Patrick's College, Maynooth, the National Seminary, in County Kildare.Some 80,000 people joined 1,000 seminarians on the grounds of the college for the brief visit. A dense fog delayed the Pope's arrival from Dublin by helicopter. The final Mass of the Pope's visit to Ireland was celebrated at Greenpark Racecoursein Limerick before 400,000 people, many more than had been expected. The Mass was offered for the people of Munster. Pope John Paul left Ireland from nearby Shannon Airport travelling to Boston where he began a six-day tour of the United States. Pope John Paul delivered 22 homilies and addresses during the course of this visit, including a televised message for the sick broadcast on RTÉ on the evening of his arrival in Ireland. Audio files of his more significant speeches are preserved on the website of the Irish Catholic Bishops Conference.Many of the temporary fixtures and ornaments at the public masses were auctioned two months after the visit to help defray its cost. A Time Remembered - The Visit of Pope John Paul II to Ireland was produced by RTÉ in 2005. Many children were named John and Paul in the aftermath of the papal visit. There were many Johns and Pauls beforehand but there was a huge increase in the amount of children called after the Pope's taken names. Some children were also given both names as their Christian name and were known as John Paul in honour of the Pope's visit. -

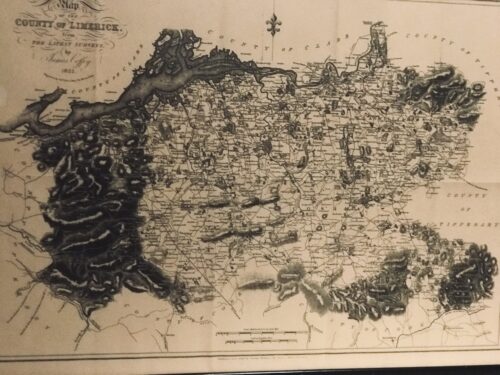

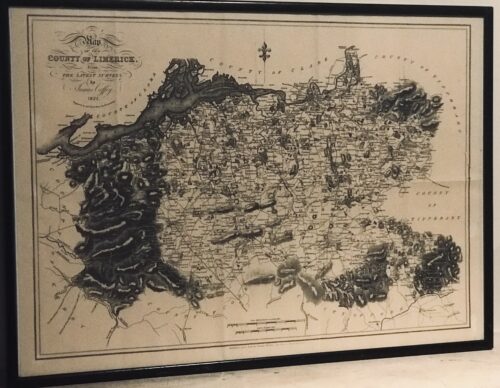

Very interesting map of Co Limerick from the 1825 surveys by the well known cartographer James Coffey.From the Latest Surveys. By James Coffey. 1825. Engraved by Sidney Hall, Bury Street, Bloomsbury. Published and sold by George McKern, 106, George Street, Limerick. Scale in Irish and English Miles. Framed and glazed. Bruree Co Limerick 45cm x 60cm

Very interesting map of Co Limerick from the 1825 surveys by the well known cartographer James Coffey.From the Latest Surveys. By James Coffey. 1825. Engraved by Sidney Hall, Bury Street, Bloomsbury. Published and sold by George McKern, 106, George Street, Limerick. Scale in Irish and English Miles. Framed and glazed. Bruree Co Limerick 45cm x 60cm -

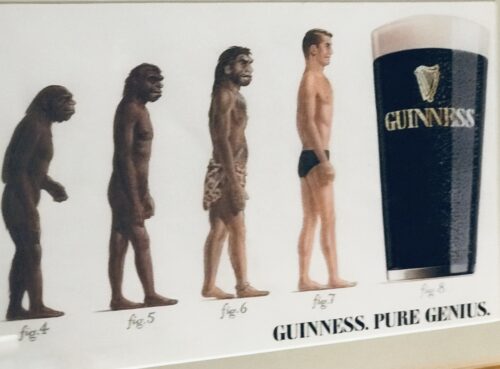

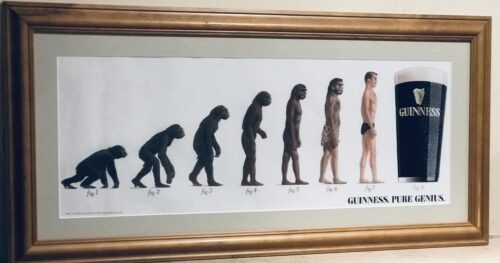

Wonderful Guinness.Pure Genius Advert from the mid 1990's with their marketing geniuses taking a whole new view on Darwinism and the Evolution of Mankind ! 85cm x 40cm Drogheda Co Louth Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks.

Wonderful Guinness.Pure Genius Advert from the mid 1990's with their marketing geniuses taking a whole new view on Darwinism and the Evolution of Mankind ! 85cm x 40cm Drogheda Co Louth Arthur Guinness started brewing ales in 1759 at the St James Gate Brewery,Dublin.On 31st December 1759 he signed a 9,000 year lease at £45 per annum for the unused brewery.Ten years later, on 19 May 1769, Guinness first exported his ale: he shipped six-and-a-half barrels to Great Britain before he started selling the dark beer porter in 1778. The first Guinness beers to use the term were Single Stout and Double Stout in the 1840s.Throughout the bulk of its history, Guinness produced only three variations of a single beer type: porter or single stout, double or extra and foreign stout for export. “Stout” originally referred to a beer’s strength, but eventually shifted meaning toward body and colour.Porter was also referred to as “plain”, as mentioned in the famous refrain of Flann O’Brien‘s poem “The Workman’s Friend”: “A pint of plain is your only man.” Already one of the top-three British and Irish brewers, Guinness’s sales soared from 350,000 barrels in 1868 to 779,000 barrels in 1876.In October 1886 Guinness became a public company, and was averaging sales of 1,138,000 barrels a year. This was despite the brewery’s refusal to either advertise or offer its beer at a discount. Even though Guinness owned no public houses, the company was valued at £6 million and shares were twenty times oversubscribed, with share prices rising to a 60 per cent premium on the first day of trading. The breweries pioneered several quality control efforts. The brewery hired the statistician William Sealy Gosset in 1899, who achieved lasting fame under the pseudonym “Student” for techniques developed for Guinness, particularly Student’s t-distribution and the even more commonly known Student’s t-test. By 1900 the brewery was operating unparalleled welfare schemes for its 5,000 employees. By 1907 the welfare schemes were costing the brewery £40,000 a year, which was one-fifth of the total wages bill. The improvements were suggested and supervised by Sir John Lumsden. By 1914, Guinness was producing 2,652,000 barrels of beer a year, which was more than double that of its nearest competitor Bass, and was supplying more than 10 per cent of the total UK beer market. In the 1930s, Guinness became the seventh largest company in the world. Before 1939, if a Guinness brewer wished to marry a Catholic, his resignation was requested. According to Thomas Molloy, writing in the Irish Independent, “It had no qualms about selling drink to Catholics but it did everything it could to avoid employing them until the 1960s.” Guinness thought they brewed their last porter in 1973. In the 1970s, following declining sales, the decision was taken to make Guinness Extra Stout more “drinkable”. The gravity was subsequently reduced, and the brand was relaunched in 1981. Pale malt was used for the first time, and isomerized hop extract began to be used. In 2014, two new porters were introduced: West Indies Porter and Dublin Porter. Guinness acquired the Distillers Company in 1986.This led to a scandal and criminal trialconcerning the artificial inflation of the Guinness share price during the takeover bid engineered by the chairman, Ernest Saunders. A subsequent £5.2 million success fee paid to an American lawyer and Guinness director, Tom Ward, was the subject of the case Guinness plc v Saunders, in which the House of Lords declared that the payment had been invalid. In the 1980s, as the IRA’s bombing campaign spread to London and the rest of Britain, Guinness considered scrapping the Harp as its logo. The company merged with Grand Metropolitan in 1997 to form Diageo. Due to controversy over the merger, the company was maintained as a separate entity within Diageo and has retained the rights to the product and all associated trademarks of Guinness.The Guinness brewery in Park Royal, London closed in 2005. The production of all Guinness sold in the UK and Ireland was moved to St. James’s Gate Brewery, Dublin. Guinness has also been referred to as “that black stuff”. Guinness had a fleet of ships, barges and yachts. The Irish Sunday Independent newspaper reported on 17 June 2007 that Diageo intended to close the historic St James’s Gate plant in Dublin and move to a greenfield site on the outskirts of the city.This news caused some controversy when it was announced.The following day, the Irish Daily Mail ran a follow-up story with a double page spread complete with images and a history of the plant since 1759. Initially, Diageo said that talk of a move was pure speculation but in the face of mounting speculation in the wake of the Sunday Independent article, the company confirmed that it is undertaking a “significant review of its operations”. This review was largely due to the efforts of the company’s ongoing drive to reduce the environmental impact of brewing at the St James’s Gate plant. On 23 November 2007, an article appeared in the Evening Herald, a Dublin newspaper, stating that the Dublin City Council, in the best interests of the city of Dublin, had put forward a motion to prevent planning permission ever being granted for development of the site, thus making it very difficult for Diageo to sell off the site for residential development. On 9 May 2008, Diageo announced that the St James’s Gate brewery will remain open and undergo renovations, but that breweries in Kilkenny and Dundalk will be closed by 2013 when a new larger brewery is opened near Dublin. The result will be a loss of roughly 250 jobs across the entire Diageo/Guinness workforce in Ireland.Two days later, the Sunday Independent again reported that Diageo chiefs had met with Tánaiste Mary Coughlan, the deputy leader of the Government of Ireland, about moving operations to Ireland from the UK to benefit from its lower corporation tax rates. Several UK firms have made the move in order to pay Ireland’s 12.5 per cent rate rather than the UK’s 28 per cent rate. Diageo released a statement to the London stock exchange denying the report.Despite the merger that created Diageo plc in 1997, Guinness has retained its right to the Guinness brand and associated trademarks and thus continues to trade under the traditional Guinness name despite trading under the corporation name Diageo for a brief period in 1997. In November 2015 it was announced that Guinness are planning to make their beer suitable for consumption by vegetarians and vegans by the end of 2016 through the introduction of a new filtration process at their existing Guinness Brewery that avoids the need to use isinglass from fish bladders to filter out yeast particles.This went into effect in 2017, per the company’s FAQ webpage where they state: “Our new filtration process has removed the use of isinglass as a means of filtration and vegans can now enjoy a pint of Guinness. All Guinness Draught in keg format is brewed without using isinglass. Full distribution of bottle and can formats will be in place by the end of 2017, so until then, our advice to vegans is to consume the product from the keg format only for now. Guinness stout is made from water, barley, roast malt extract, hops, and brewer’s yeast. A portion of the barley is roasted to give Guinness its dark colour and characteristic taste. It is pasteurisedand filtered. Until the late 1950s Guinness was still racked into wooden casks. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Guinness ceased brewing cask-conditioned beers and developed a keg brewing system with aluminium kegs replacing the wooden casks; these were nicknamed “iron lungs”.Until 2016 the production of Guinness, as with many beers, involved the use of isinglass made from fish. Isinglass was used as a fining agent for settling out suspended matter in the vat. The isinglass was retained in the floor of the vat but it was possible that minute quantities might be carried over into the beer. Diageo announced in February 2018 that the use of isinglass in draught Guinness was to be discontinued and an alternative clarification agent would be used instead. This has made draught Guinness acceptable to vegans and vegetarians. Arguably its biggest change to date, in 1959 Guinness began using nitrogen, which changed the fundamental texture and flavour of the Guinness of the past as nitrogen bubbles are much smaller than CO2, giving a “creamier” and “smoother” consistency over a sharper and traditional CO2 taste. This step was taken after Michael Ash – a mathematician turned brewer – discovered the mechanism to make this possible. Nitrogen is less soluble than carbon dioxide, which allows the beer to be put under high pressure without making it fizzy. High pressure of the dissolved gas is required to enable very small bubbles to be formed by forcing the draught beer through fine holes in a plate in the tap, which causes the characteristic “surge” (the widget in cans and bottles achieves the same effect). This “widget” is a small plastic ball containing the nitrogen. The perceived smoothness of draught Guinness is due to its low level of carbon dioxide and the creaminess of the head caused by the very fine bubbles that arise from the use of nitrogen and the dispensing method described above. “Foreign Extra Stout” contains more carbon dioxide, causing a more acidic taste. Contemporary Guinness Draught and Extra Stout are weaker than they were in the 19th century, when they had an original gravity of over 1.070. Foreign Extra Stout and Special Export Stout, with abv of 7.5% and 9% respectively, are perhaps closest to the original in character.Although Guinness may appear to be black, it is officially a very dark shade of ruby. The most recent change in alcohol content from the Import Stout to the Extra Stout was due to a change in distribution through North American market. Consumer complaints have influenced recent distribution and bottle changes. Studies claim that Guinness can be beneficial to the heart. Researchers found that “‘antioxidantcompounds’ in the Guinness, similar to those found in certain fruits and vegetables, are responsible for the health benefits because they slow down the deposit of harmful cholesterol on the artery walls.”Guinness ran an advertising campaign in the 1920s which stemmed from market research – when people told the company that they felt good after their pint, the slogan, created by Dorothy L. Sayers–”Guinness is Good for You”. Advertising for alcoholic drinks that implies improved physical performance or enhanced personal qualities is now prohibited in Ireland.Diageo, the company that now manufactures Guinness, says: “We never make any medical claims for our drinks. -

Out of stock

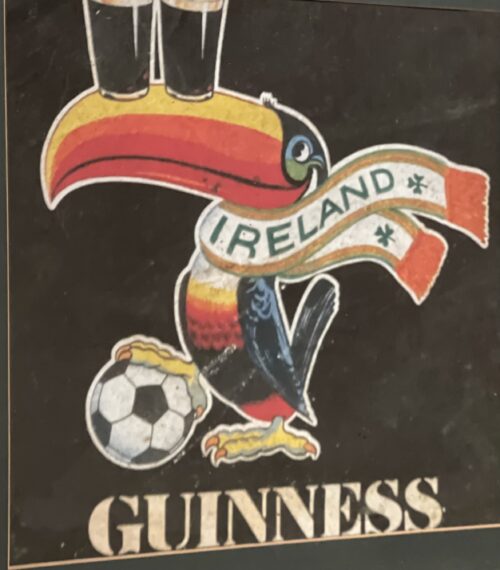

51cm x 51cm Imagination is something Guinness Advertising has never been short of… From John Gilroy’s hapless zookeeper and his menagerie of creatures to a Polynesian surfer and a herd of white horses; from messages in bottles setting sail across the ocean to a single, heart-stoppingly enormous wave. Guinness have been carving out their own creative path for almost a century with decades of extraordinary and enduring print, TV and digital campaigns to their name, and hopefully they will continue to push boundaries to tell stories to the world. Here’s to original thinking !

51cm x 51cm Imagination is something Guinness Advertising has never been short of… From John Gilroy’s hapless zookeeper and his menagerie of creatures to a Polynesian surfer and a herd of white horses; from messages in bottles setting sail across the ocean to a single, heart-stoppingly enormous wave. Guinness have been carving out their own creative path for almost a century with decades of extraordinary and enduring print, TV and digital campaigns to their name, and hopefully they will continue to push boundaries to tell stories to the world. Here’s to original thinking ! -

Original Resin Guinness Toucan (manufactured by Shannon) Dimensions :20cm x 10cm x 8cm 0.5kg For nearly two centuries of existence, the Guinness brewery had almost no need to formally advertise, allowing word-of-mouth to sell the beer, and sell it did. By the late 19th century, Guinness was one of the top three breweries between Britain and Ireland. In 1862, the company adopted an Irish harp as their logo and trademarked it in 1875. However, by the late 1920s, sales were declining, and in 1929, Rupert Guinness, then chair of the company, ran the first-ever Guinness print ad with the slogan “Guinness is good for you.” The very next year, the brewery hired advertising firm S.H. Benson. It was then, in 1930, that the story of the Guinness toucan began. The man responsible for the iconic bird and his animal companions is the English illustrator and draftsman John Gilroy. He was born in 1898 in Newcastle upon Tyne into a family of eight children, and his father, William, was a landscape painter. From a young age, Gilroy began copying the drawings in magazines, and it was quickly evident he would follow in his father’s professional footsteps. By 15, he was a cartoonist for the local newspaper. He won a scholarship to art school, and although World War I interrupted his studies, he entered London’s Royal College of Art in 1919. While he was still a student, he received his first commission for commercial art—a promotional pamphlet for the Hydraulic Engineering Co. Not long after graduating, Gilroy began working for S.H. Benson, where he would eventually work on Guiness.His first work with the firm was on campaigns for Skipper Sardines and Virol (a brand of malt extract). In his early years at Benson, he and his colleagues created clever characters to make their designs memorable: Baron de Beef, Signor Spaghetti, Miss Di Gester. All these playful characters likely primed Gilroy for the fun and whimsical designs he would eventually draw for Guinness in his 35 years working with the company. In the early 1930s S.H. Benson boasted an impressive staff of creatives beyond John Gilroy; the late Dorothy Sayers, now famous as a crime writer and poet, wrote copy for the agency. When Guinness approached the firm, they had an interesting request: the final advertising campaign should not be too much to do with beer, despite the fact that it was advertising—well—beer. They thought it would be vulgar. Instead, they preferred something that appealed to families and that highlighted the purported health benefits of the brew. They asked Gilroy to draft an ad showing a family drinking Guinness, but no one could seem to agree on what the family should look like, nor how they should be presented. Luckily, it was precisely family that led Gilroy to the particular idea that eventually spawned Guinness’s most famous ad campaigns. The artist had recently taken his son to the circus, recounts Guinness archive manager Fergus Brady, and had watched a sea lion balancing a ball on its nose. He realized how fun it would be to draw a sea lion balancing a pint of Guinness on its nose, and pitched the idea to Guinness. From there the series expanded to an entire menagerie. Gilroy drew ostriches, bears, pelicans, kangaroos, and of course, the toucan. Paired with Sayers’s inventive copy, the ads took off. In her most clever ad, she plays on the toucan / two-can homophone and on the idea that drinking Guinness offers a range of health benefits: “If he can say as you can / Guinness is good for you / How grand to be a Toucan — / Just think what Toucan do.” The illustration features a smiling toucan perched next to two shining pint glasses full of Guinness stout.